In Māori mythology, the primal couple Rangi and Papa (or Ranginui and Papatūānuku) appear in a creation myth explaining the origin of the world (though there are many different versions). In some South Island dialects, Rangi is called Raki or Rakinui. The Māori are the indigenous Polynesian people of New Zealand, originating with settlers from eastern Polynesia, who arrived in New Zealand in several waves of canoe voyages some time between 1250 and 1300. Over several centuries in isolation, the Polynesian settlers developed a unique culture, with their own language, a rich mythology, and distinctive crafts and performing arts. Early Māori formed tribal groups based on eastern Polynesian social customs and organization. Horticulture flourished using plants they introduced; later, a prominent warrior culture emerged. For more on the Māori, please see the ASAD articles of April 27, 2017, and April 26, 2018.

Māori myths are set in the remote past and their content often have to do with the supernatural. They present Māori ideas about the creation of the universe and the origins of gods and of people. The mythology accounts for natural phenomena, the weather, the stars and the moon, the fish of the sea, the birds of the forest, and the forests themselves. Much of the culturally institutional behavior of the people finds its sanctions in myth. B.G. Biggs’s article, ‘Maori Myths and Traditions’ in the Encyclopaedia of New Zealand states that,

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of myth, as distinct from tradition, is its universality. Each of the major myths is known in some version not only throughout New Zealand but also over much of Polynesia as well.

The Māori understanding of the development of the universe was expressed in genealogical form. These genealogies appear in many versions, in which several symbolic themes constantly recur. According to Biggs,

Evolution may be likened to a series of periods of darkness (pō) or voids (kore), each numbered in sequence or qualified by some descriptive term. In some cases the periods of darkness are succeeded by periods of light (ao). In other versions the evolution of the universe is likened to a tree, with its base, tap roots, branching roots, and root hairs. Another theme likens evolution to the development of a child in the womb, as in the sequence “the seeking, the searching, the conception, the growth, the feeling, the thought, the mind, the desire, the knowledge, the form, the quickening”. Some, or all, of these themes may appear in the same genealogy.

The cosmogonic genealogies are usually brought to a close by the two names Rangi and Papa (father sky and mother earth). The marriage of this celestial pair produced the gods and, in due course, all the living things of the earth.

The earliest full account of the origins of gods and the first human beings is contained in a manuscript entitled Nga Tama a Rangi (The Sons of Heaven), written in 1849 by Wī Maihi Te Rangikāheke, of the Ngāti Rangiwewehi tribe of Rotorua. The manuscript “gives a clear and systematic account of Māori religious beliefs and beliefs about the origin of many natural phenomena, the creation of woman, the origin of death, and the fishing up of lands. No other version of this myth is presented in such a connected and systematic way, but all early accounts, from whatever area or tribe, confirm the general validity of the Rangikāheke version. It begins as follows:

My friends, listen to me. The Māori people stem from only one source, namely the Great-heaven-which-stands-above, and the Earth-which-lies-below. According to Europeans, God made heaven and earth and all things. According to the Māori, Heaven (Rangi) and Earth (Papa) are themselves the source.

Ranginui

- Rangi (“Sky”)

- Raki (“Sky”) in the South Island

- Ranginui (“Great Sky”)

- Rangi-pōtiki (“Rangi the Lastborn”): possibly another name of Rangi, or a closely allied deity

Papatuanuku

- Papa (“world”)

- Papatūānuku (“world separated”), (Earth), (Mother Earth)

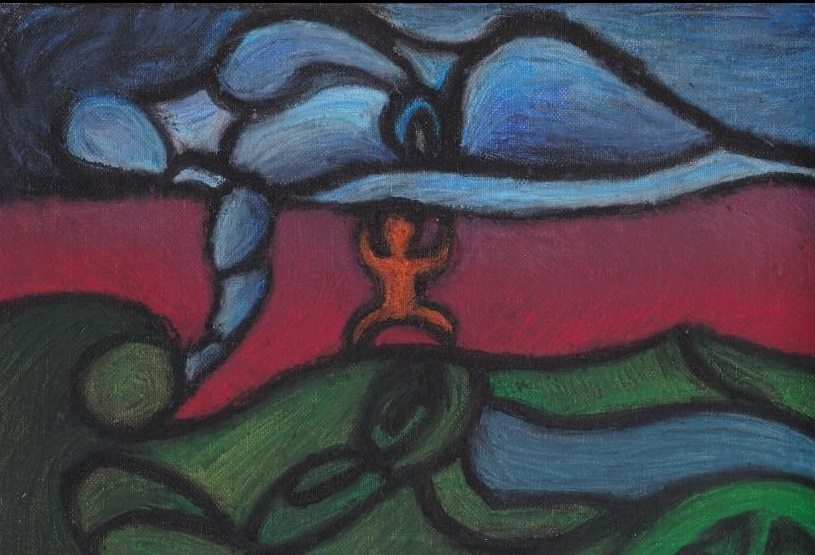

Ranginui and Papatūānuku are the primordial parents, the sky father and the earth mother who lie locked together in a tight embrace. They have many children all of whom are male, who are forced to live in the cramped darkness between them. These children grow and discuss among themselves what it would be like to live in the light. Tūmatauenga, the fiercest of the children, proposes that the best solution to their predicament is to kill their parents.

His brother Tāne disagrees, suggesting that it is better to push them apart, to let Ranginui be as a stranger to them in the sky above while Papatūānuku will remain below to nurture them. The others put their plans into action — Rongo, the god of cultivated food, tries to push his parents apart, then Tangaroa, the god of the sea, and his sibling Haumia-tiketike, the god of wild food, join him. In spite of their joint efforts Rangi and Papa remain close together in their loving embrace. After many attempts Tāne, god of forests and birds, forces his parents apart. Instead of standing upright and pushing with his hands as his brothers have done, he lies on his back and pushes with his strong legs. Stretching every sinew Tāne pushes and pushes until, with cries of grief and surprise, Ranginui and Papatūānuku were pried apart.

And so the children of Ranginui and Papatūanuku see light and have space to move for the first time. While the other children have agreed to the separation Tāwhirimātea, the god of storms and winds, is angered that the parents have been torn apart. He cannot bear to hear the cries of his parents nor see the tears of Ranginui as they are parted, he promises his siblings that from henceforth they will have to deal with his anger. He flies off to join Rangi and there carefully fosters his own many offspring who include the winds, one of whom is sent to each quarter of the compass. To fight his brothers, Tāwhirimātea gathers an army of his children — winds and clouds of different kinds, including fierce squalls, whirlwinds, gloomy thick clouds, fiery clouds, hurricane clouds and thunderstorm clouds, and rain, mists and fog. As these winds show their might the dust flies and the great forest trees of Tāne are smashed under the attack and fall to the ground, food for decay and for insects.

Then Tāwhirimātea attacks the oceans and huge waves rise, whirlpools form, and Tangaroa, the god of the sea, flees in panic. Punga, a son of Tangaroa, has two children, Ikatere father of fish, and Tu-te-wehiwehi (or Tu-te-wanawana) the ancestor of reptiles. Terrified by Tāwhirimātea’s onslaught the fish seek shelter in the sea and the reptiles in the forests. Ever since Tangaroa has been angry with Tāne for giving refuge to his runaway children. So it is that Tāne supplies the descendants of Tūmatauenga with canoes, fishhooks and nets to catch the descendants of Tangaroa. Tangaroa retaliates by swamping canoes and sweeping away houses, land and trees that are washed out to sea in floods.

Tāwhirimātea next attacks his brothers Rongo and Haumia-tiketike, the gods of cultivated and uncultivated foods. Rongo and Haumia are in great fear of Tāwhirimātea but, as he attacks them, Papatūānuku determines to keep these for her other children and hides them so well that Tāwhirimātea cannot find them. So Tāwhirimātea turns on his brother Tūmatauenga. He uses all his strength but Tūmatauenga stands fast and Tāwhirimatea cannot prevail against him. Tū (or human kind) stands fast and, at last, the anger of the gods subsided and peace prevailed.

Tū thought about the actions of Tāne in separating their parents and made snares to catch the birds, the children of Tāne who could no longer fly free. He then made nets from forest plants and casts them in the sea so that the children of Tangaroa soon lie in heaps on the shore. He made hoes to dig the ground, capturing his brothers Rongo and Haumia-tiketike where they have hidden from Tāwhirimātea in the bosom of the earth mother and, recognising them by their long hair that remains above the surface of the earth, he drags them forth and heaps them into baskets to be eaten. So Tūmatauenga eats all of his brothers to repay them for their cowardice; the only brother that Tūmatauenga does not subdue is Tāwhirimātea, whose storms and hurricanes attack humankind to this day.

There was one more child of Ranginui and Papatūānuku who was never born and still lives inside Papatūanuku. Whenever this child is kicking the earth shakes and it causes an earthquake. Rūaumoko is his name and he is the God of earthquakes and volcanoes.

Tāne searched for heavenly bodies as lights so that his father would be appropriately dressed. He obtained the stars and threw them up, along with the moon and the sun. At last Ranginui looked handsome. Ranginui and Papatūanuku continue to grieve for each other to this day. Ranginui’s tears fall towards Papatūanuku to show how much he loves her. Sometimes Papatūanuku heaves and strains and almost breaks herself apart to reach her beloved partner again but it is to no avail. When mist rises from the forests, these are Papatūānuku’s sighs as the warmth of her body yearns for Ranginui and continues to nurture mankind.

On August 24, 1990, New Zealand Post released a set of six stamps honoring the Tangata Whenua — the original people of the land (Scott #997-1002). This was the final in the six part series leading up to the 150th Anniversary of New Zealand in 1990. The six stamps each depict a different aspect of Māori culture shown through story-telling, craft-work, and song or dance. They were designed by K. Hall of Christchurch and printed using lithography by Leigh-Mardon in Australia in sheets of 100 stamps, perforated 14 x 14¼. They remained on sale until August 24, 1991.

For an interpretation of the Rangi and Papa creation myth, please have a look at this page on the Victoria University of Wellington Library’s website.

One thought on “The Māori Legend of Rangi and Papa”