Costa Rica – Scott #178 (1936)

I have been fascinated by maps ever since I was quite young. I can vividly recall enthusiastically gathering free maps from gas stations whenever my family would take an extended trip in our car. I suppose I began “collecting” maps even before I began collecting stamps and coins. Of course, back then it was more of an accumulation than anything else leading to my mother’s nickname for me: “pack rat”. By the time I was in high school, I looked forward to the annual sports shows at the local civic arena where I would visit the tourism booths looking for free maps and travel guides. My favorites were the state maps. I joined the National Geographic Society the year that I graduated high school and looked forward to the maps that were periodically included in the magazine; I’ve remained a member ever since.

It was only natural for my love of maps to manifest itself into my expanding hobby of collecting stamps and I was always pleased to find stamps picturing maps. I can’t say that I actively pursued “maps on stamps” as a topical collection per se but I do have quite a few of them. Obviously, most show the national or territorial boundaries of the issuer itself but sometimes the map will be of some smaller area which requires a bit of research to locate. Such is the case for today’s featured stamp. For only the second time in A Stamp A Day’s 561 posts, I found myself unable to match a stamp with the date. I decided to choose a random stamp; I happened to look first in a folder of my scanned stamps marked “Maps” and picked immediately picked Scott #178 from Costa Rica. I’d never heard of Isla del Coco but — because of the ships included in the design — I thought there might be a connection to Christopher Columbus, another favorite subject.

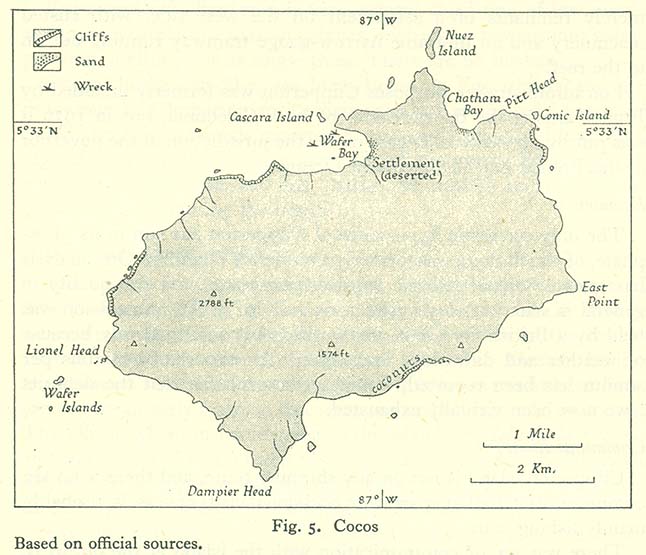

Cocos Island (Isla del Coco) is designated as a National Park off the shore of Costa Rica, that does not allow inhabitants other than Costa Rican Park Rangers. It constitutes the 11th of the 13 districts of Puntarenas Canton of the province of Puntarenas. It is located in the Pacific Ocean, approximately 342 miles (297 nautical miles, or 550 kilometers) from the Pacific shore of Costa Rica. With an area of approximately 9.21 square miles (23.85 km²), about 5 miles by 2 miles (8 km × 3 km) and a perimeter of around 14.5 miles (23.3 km), the island is more or less rectangular in shape.

Surrounded by deep waters with counter-currents, Cocos Island is admired by scuba divers for its populations of hammerhead sharks, rays, dolphins and other large marine species. The extremely wet climate and oceanic character give Cocos an ecological character that is not shared with either the Galápagos Archipelago or any of the other islands (for example, Malpelo, Gorgona or Coiba) in this region of the world. It is of both volcanic and tectonic origin, the only emergent island of the Cocos Plate — one of the minor tectonic plates. Potassium-argon dating established the age of the oldest rocks between 1.91 and 2.44 million years (Late Pliocene) and it is composed primarily of basalt, which is formed by cooling lava.

The landscape is mountainous and irregular and the summit is Cerro Iglesias at 1,888 feet (575.5 meters). In spite of its mountainous character, there are flatter areas between 200–260 m in elevation in the central part of the island, which are said to be a transitional stage of the geomorphological cycle of V-shaped valleys. With four bays, three of them in the north side (Wafer, Chatham and Weston), Cocos Island has a number of short rivers and streams that drain the abundant rainfall into them. Due to large, 300-foot cliffs that ring much of the island, the easiest point of entry is at Chatham Bay. The largest rivers are the Genio and the Pittier, which drain their water into Wafer Bay. The mountainous landscape and the tropical climate combine to create over 200 waterfalls throughout the island. The island’s soils are classified as entisols which are highly acidic and could be easily eroded by the island’s high rainfall on the steep slopes, were it not for the dense forest coverage.

The climate of the island is mostly determined by the latitudinal movement of the Intertropical Convergence Zone which creates cloudiness and precipitation that is constant throughout the year. This makes the climate in the island humid and tropical with an average annual temperature of 79.9 °F (26.6 °C) and an average annual rainfall of over 276 inches (7,000 millimeters). Rainfall is high throughout the year, although lower from January through March and slightly lower during late September and October. Numerous oceanic currents from the central Pacific Ocean that converge on the island also have an important influence.

Accroding to the 16th-century historian Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo in his book Historia General y Natural de las Indias, Islas y Tierra Firme del Mar Océano (Seville, 1535), Cocos Island was discovered by Spanish navigator Juan de Cabezas (also known as Juan de Grado) from Avilés in 1526. The first document with the name Isle de Coques is a map painted on parchment, called that of Henry II that appeared in 1542 during the reign of Francis I of France. The planisphere of Nicolás Desliens (1556, Dieppe) places this Ysle de Coques about one and half degrees north of the Equator. Blaeu’s Grand Atlas, originally published in 1662, has a color world map on the back of its front cover which shows I. de Cocos right on the Equator. Frederik De Witt’s Atlas (1680) shows it similarly. The Hondius Broadside map of 1590 shows I. de Cocos at the latitude of 2 degrees and 30 minutes northern latitude, while in 1596 Theodore de Bry shows the Galápagos Islands near 6 degrees north of the Equator. Emanuel Bowen in A Complete system of Geography, Volume II (London, 1747) states that the Galápagos stretch 5 degrees north of the Equator.

The island became part of Costa Rica in 1832 by decree No. 54 of the Constitutional Assembly of the free state of Costa Rica. Whalers stopped at Cocos Island regularly until the mid-19th century, when inexpensive kerosene started to replace whale oil for lighting.

In October 1863, the ship Adelante dumped 426 Tongan ex-slaves on the island, the captain being too lazy to take them home as promised. When they were saved by the Tumbes, one month later, only 38 had survived, as the rest had perished from smallpox.

The first claims of treasure buried on the island came from a woman named Mary Welsh, who claimed 350 tons of gold (about $16 billion in today’s money) raided from Spanish galleons had been buried on the island. She had been a member of a pirate crew led by Captain Bennett Graham, and was transported to an Australian penal colony for her crimes. She possessed a chart showing where Graham’s treasure was supposed to be hidden. On her release she returned to the island with an expedition, which had no success in finding anything, with the points of reference in the chart having disappeared.

Another pirate supposed to have buried treasure on the island was the Portuguese Benito Bonito. Though Bonito was hunted down and executed, his treasure was never retrieved.

The best known of the treasure legends tied to the island is that of the Treasure of Lima. In 1820, with the army of José de San Martín approaching Lima, Viceroy José de la Serna is supposed to have entrusted treasure from the city to British trader Captain William Thompson for safekeeping until the Spaniards could secure the country. Instead of waiting in the harbor as they were instructed, Thompson and his crew killed the Viceroy’s men and sailed to Cocos, where they buried the treasure. Shortly afterwards, they were apprehended by a Spanish warship. All of the crew except Thompson and his first mate were executed for piracy. The two said they would show the Spaniards where they had hidden the treasure in return for their lives — but after landing on Cocos, they escaped into the forest.

Hundreds of attempts to find treasure on the island have failed. Several early expeditions were mounted on the basis of claims by a man named Keating, who was supposed to have befriended Thompson. On one trip, Keating was said to have retrieved gold and jewels from the treasure. Prussian adventurer August Gissler lived on the island for most of the period from 1889 until 1908, hunting the treasure with the small success of finding six gold coins. The Costa Rican government named Gissler the first Governor of Cocos Island in 1897 and allowed him to establish a short-lived colony there.

On May 12, 1970, the insular territory of Cocos Island was incorporated administratively into Central Canton of the Province of Puntarenas by means of Executive Decree No. 27, making it the Eleventh District of Central Canton. Cocos Island was declared a Costa Rican National Park by means of Executive Decree in 1978. Cocos Island National Park was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1997. In 2002, the World Heritage Site designation was extended to include an expanded marine zone of 771 square miles (1,997 km²). In addition, it is included in the list of “Wetlands of International Importance”. The island’s 33 residents, the Costa Rican park rangers, were allowed to vote for the first time in Costa Rica’s February 5, 2006, election.

In 2009 Cocos Island was short-listed as a candidate to be declared one of the New7Wonders of Nature of the world by the New7Wonders of the World Foundation, and ranked second in the islands category. Thanks to the breathtaking marine life in its waters, Cocos Island was named one of the best ten scuba diving spots in the world by PADI (Professional Association of Diving Instructors) and a “must do” according to diving experts.

For many, the main attractions are the large pelagic fish species, which are very abundant in this unique meeting point between deep and shallow waters. The largest schools of hammerhead sharks in the World are consistently reported there. Encounters with dozens if not hundreds of these and other large animals are nearly certain in every dive. Smaller and colorful species are also abundant in one of the most extensive and rich reefs of the south eastern Pacific. The famous oceanographer Jacques Cousteau visited the island several times and in 1994 called it “the most beautiful island in the world”. These numerous accolades highlight the urgent need to protect Cocos Island and surrounding waters from illegal large-scale fishing, poaching and other threats.

Cocos Island is home to dense tropical moist forests. It is the only oceanic island in the eastern Pacific region with such rain forests and their characteristic types of flora and fauna. The cloud forests at higher elevations are also unique in the eastern Pacific. The island was never linked to a continent, so the flora and fauna arrived via long distance dispersal from the Americas. The island has therefore a high proportion of endemic species.

The only persons allowed to live on Cocos Island are Costa Rican Park Rangers, who have established two encampments, including one at English Bay. Tourists and ship crew members are allowed ashore only with permission of island rangers, and are not permitted to camp, stay overnight or collect any flora, fauna or minerals from the island. Occasional amateur radio DXpeditions are allowed to visit.

The island, however, is under growing human pressure. Illegal poaching of large marine species in and around its protected waters has become a main concern. Growing local and worldwide demand for tuna, shark fin soup and other seafood is threatening the island’s fragile ecosystems. The government of Costa Rica has been openly accused of passivity and even benefiting corruptly from illegal shark fin and other seafood trade to large markets, such as China and other Asian countries. The government has shown some willingness to protect the island’s natural riches and prosecute poachers. However, efforts to effectively patrol the waters and enforce environmental laws face big financial and bureaucratic difficulties, as well as being prone to the corruption of local, national and international authorities.

Recent events show that large-scale illegal poaching keeps happening. Despite initial hope in stopping and charging poachers,[45] who have been caught with abundant evidence, they have been quickly released under suspicious circumstances. Also, efforts to raise funds for protection have been dwarfed. Marvin Orlando Cerdas, a judge with the local Puntarenas Court of Justice, obscurely allowed 22 poachers caught red-handed to escape the country. Also under highly suspicious and allegedly corrupt circumstances, District Attorney Michael Morales Molina stopped the auction for public benefit of confiscated goods, immediately after the spokesman of the large illegal poacher ship Tiuna simply made the request.

The book Desert Island proposed the highly detailed theory that Daniel Defoe used Cocos Island as an accurate model for his descriptions of the island inhabited by the marooned Robinson Crusoe. However, Defoe placed Crusoe’s island not in the Pacific, but rather off the coast of Venezuela in the Atlantic Ocean. Robinson’s neighboring Terra Firma is shown on the color map of Joannes Jansson (Amsterdam) depicting the northeastern corner of South America, entitled Terra Firma et Novum Regnum Granatense et Popayan. It belongs to the early group of plates printed by Willem Blaeu from 1630 onwards. The properly called Terra Firma was the Isthmus of Darien. Crusoe’s two references to Mexico are against a South American island as well.

Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park novel (and subsequent movies) takes place in the fictitious Isla Nublar of Costa Rica, which is modeled after Cocos Island. The video game Jurassic Park: Trespasser, from 1998, uses a map of Cocos Island to illustrate the island. The Clive Cussler novel The Silent Sea (2010) references mystic Chinese pirate tales but locates the island off the northern Pacific coast of the United States.

On January 29, 1936, Costa Rica released a set of eight stamps picturing the map of Cocos Island in various colors and in denominations of 4, 8, 25, 35, 40, and 50 centimos, plus 2 and 5 colons against a plain background (Scott #169-176). Perforated 14 except for the 25-centimo value which was 11½, the five highest values (except for the 50-centimo) were surcharged with new denominations (Scott #196-200). Earlier, the 50-centimo had received an overprint and two different surcharges (15 centimos in black and 30 centimos in blue) to mark Pan-American Aviation Day, declared by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, on December 17, 1940 (Scott #C55-56). On December 5, 1936, the denominations of 5 centimos and 10 centimos were added to the basic Cocos Islands set of stamps (Scott #177-178). However, the frames were changed and the plain background gave way to one that added the three ships of Christopher Columbus and removed the geographical labels. These were perforated 12. Scott #177 was printed in green while Scott #178 is carmine rose. Both of these stamps were overprinted with OFICIAL in black ink in 1936 (Scott #O80-O81) with the 5-centimo receiving an additional overprint — CORREOS / 1947 in red — on March 19, 1947 (Scott #247). Cocos Island wouldn’t appear on another Costa Rican stamp until November 5, 1992, when the 400th anniversary of its discovery was commemorated by a pair of stamps, one portraying the coastline with a waterfall on the other (Scott #446-447).

Although Scott #178 pictures Columbus’ ships below the map of Cocos Island, the explorer never came close to visiting the area. Christopher Columbus only reached the eastern coast of Costa Rica, making landfall during his fourth voyage on September 18, 1502.

One thought on “Isla del Coco”