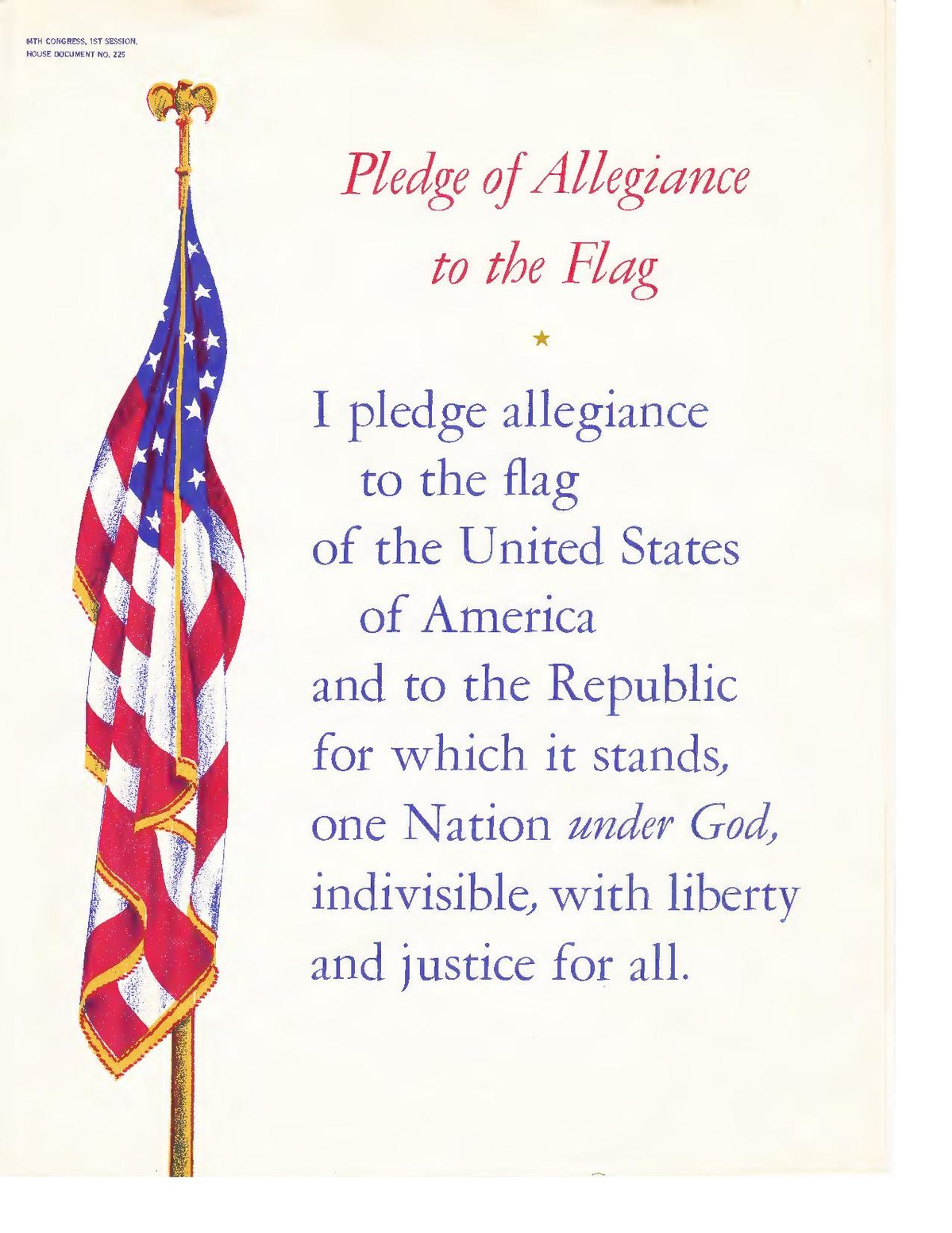

On June 22, 1942, the Pledge of Allegiance of the United States was formally adopted by U.S. Congress. The pledge is an expression of allegiance to the Flag of the United States and the republic of the United States of America. It was originally composed by Captain George Thatcher Balch, a Union Army Officer during the Civil War and later a teacher of patriotism in New York City schools. The form of the pledge used today was largely devised by Francis Bellamy in 1892, and formally adopted by Congress as the pledge in 1942. The official name of The Pledge of Allegiance was adopted in 1945. The most recent alteration of its wording came on Flag Day in 1954, when the words “under God” were added.

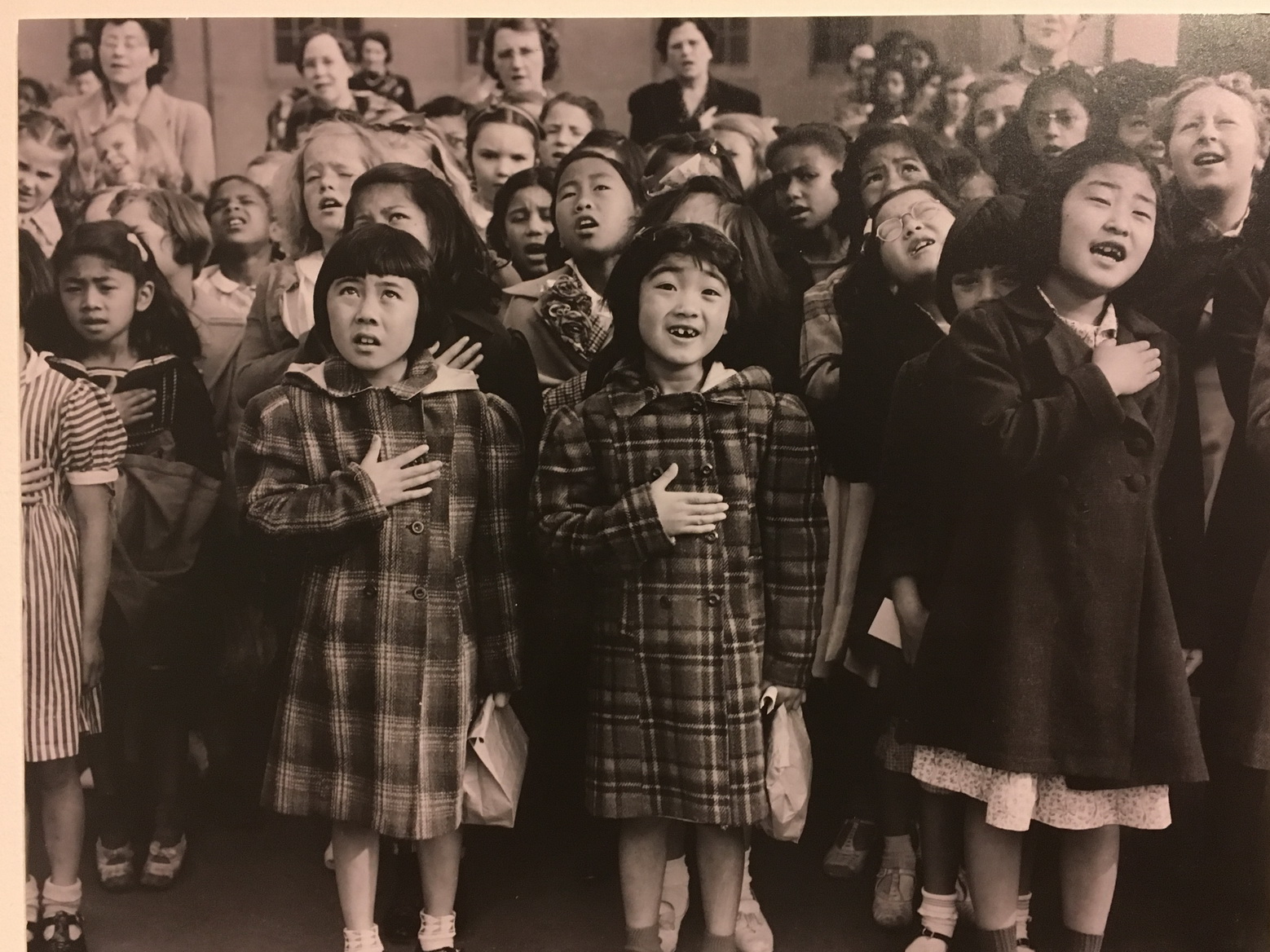

Congressional sessions open with the recital of the Pledge, as do many government meetings at local levels, and meetings held by many private organizations. All states except Hawaii, Iowa, Vermont and Wyoming require a regularly-scheduled recitation of the pledge in the public schools, although the Supreme Court has ruled in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette that students cannot be compelled to recite the Pledge, nor can they be punished for not doing so. In a number of states, state flag pledges of allegiance are required to be recited after this.

The United States Flag Code says:

The Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag—”I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one Nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”[12]—should be rendered by standing at attention facing the flag with the right hand over the heart. When not in uniform men should remove any non-religious headdress with their right hand and hold it at the left shoulder, the hand being over the heart. Persons in uniform should remain silent, face the flag, and render the military salute. Members of the Armed Forces not in uniform and veterans may render the military salute in the manner provided for persons in uniform.

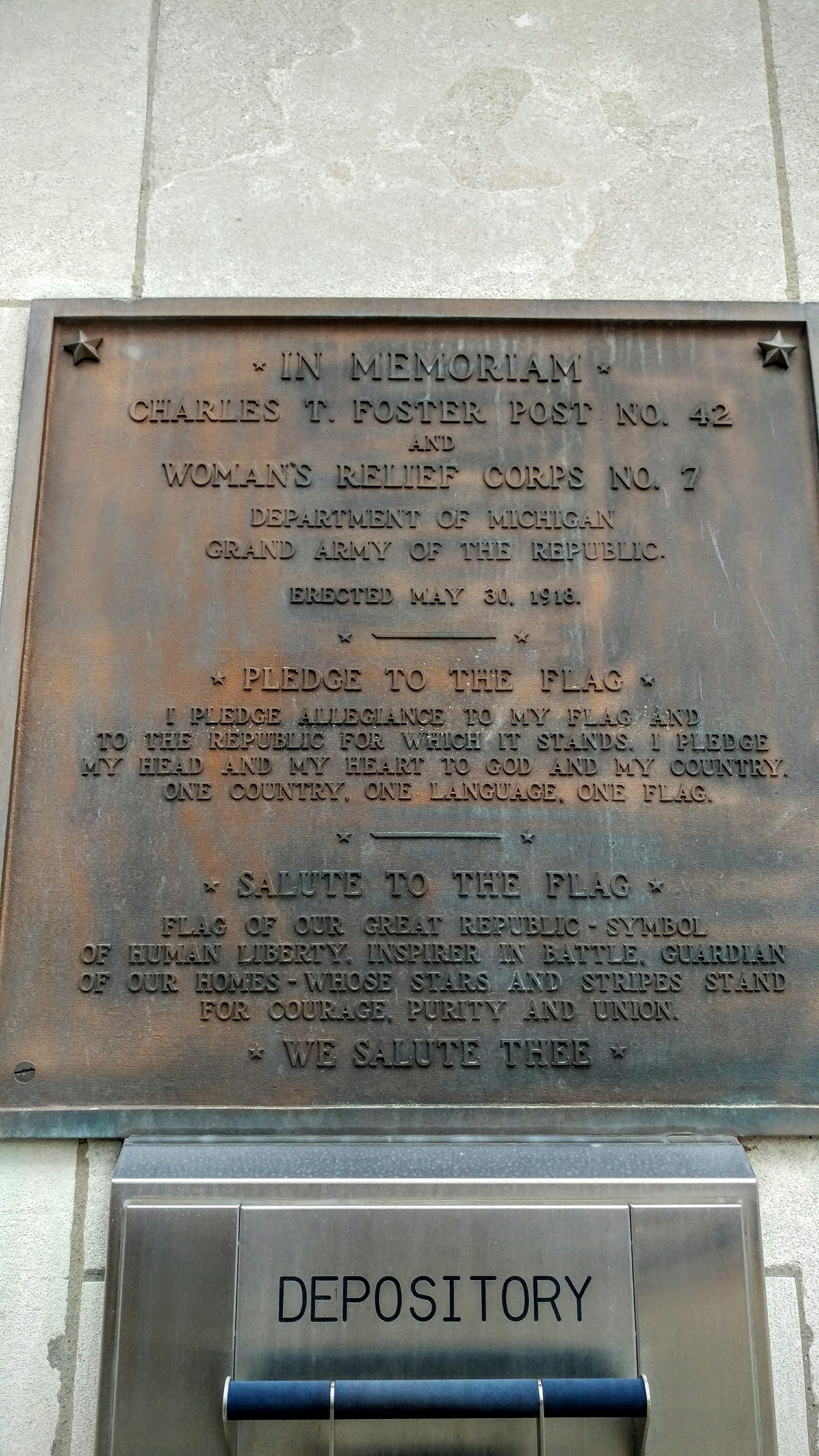

The Pledge of Allegiance, as it exists in its current form, was composed in August 1892 by Francis Bellamy, who was a Baptist minister, a Christian socialist, and the cousin of socialist utopian novelist Edward Bellamy. There did exist a previous version created by Rear Admiral George Balch, a veteran of the Civil War, who later become auditor of the New York Board of Education. Balch’s pledge, which existed contemporaneously with the Bellamy version until the 1923 National Flag Conference, read:

We give our heads and hearts to God and our country; one country, one language, one flag!

Balch was a proponent of teaching children, especially those of immigrants, loyalty to the United States, even going so far as to write a book on the subject and work with both the government and private organizations to distribute flags to every classroom and school. Balch’s pledge, which predates Bellamy’s by five years and was embraced by many schools, by the Daughters of the American Revolution until the 1910s, and by the Grand Army of the Republic until the 1923 National Flag Conference, is often overlooked when discussing the history of the Pledge. Bellamy, however, did not approve of the pledge as Balch had written it, referring to the text as “too juvenile and lacking in dignity.”

The Bellamy “Pledge of Allegiance” was first published in the September 8 issue of the popular children’s magazine The Youth’s Companion as part of the National Public-School Celebration of Columbus Day, a celebration of the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Americas. The event was conceived and promoted by James B. Upham, a marketer for the magazine, as a campaign to instill the idea of American nationalism in students and to sell flags to public schools. According to author Margarette S. Miller, this campaign was in line both with Upham’s patriotic vision as well as with his commercial interest. According to Miller, Upham “would often say to his wife: ‘Mary, if I can instill into the minds of our American youth a love for their country and the principles on which it was founded, and create in them an ambition to carry on with the ideals which the early founders wrote into The Constitution, I shall not have lived in vain.'”

Bellamy’s original Pledge read:

I pledge allegiance to my Flag and the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

The Pledge was supposed to be quick and to the point. Bellamy designed it to be recited in 15 seconds. As a socialist, he had initially also considered using the words equality and fraternity but decided against it, knowing that the state superintendents of education on his committee were against equality for women and African Americans.

Francis Bellamy and Upham had lined up the National Education Association to support the Youth’s Companion as a sponsor of the Columbus Day observance and the use in that observance of the American flag. By June 29, 1892, Bellamy and Upham had arranged for Congress and President Benjamin Harrison to announce a proclamation making the public school flag ceremony the center of the Columbus Day celebrations. This arrangement was formalized when Harrison issued Presidential Proclamation 335. Subsequently, the Pledge was first used in public schools on October 12, 1892, during Columbus Day observances organized to coincide with the opening of the World’s Columbian Exposition (the Chicago World’s Fair), Illinois.

In his recollection of the creation of the Pledge, Francis Bellamy said, “At the beginning of the nineties patriotism and national feeling was (sic) at a low ebb. The patriotic ardor of the Civil War was an old story … The time was ripe for a reawakening of simple Americanism and the leaders in the new movement rightly felt that patriotic education should begin in the public schools.” James Upham “felt that a flag should be on every schoolhouse,” so his publication “fostered a plan of selling flags to schools through the children themselves at cost, which was so successful that 25,000 schools acquired flags in the first year (1892-1893).

As the World’s Columbian Exposition was set to celebrate the 400th anniversary the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Americas, Upham sought to link the publication’s flag drive to the event, “so that every school in the land … would have a flag raising, under the most impressive conditions.” Bellamy was placed in charge of this operation and was soon lobbying “not only the superintendents of education in all the States, but [he] also worked with governors, Congressmen, and even the President of the United States.” The publication’s efforts paid off when Benjamin Harrison declared Wednesday October 12, 1892, to be Columbus Day for which The Youth’s Companion made “an official program for universal use in all the schools.” Bellamy recalled that the event “had to be more than a list of exercises. The ritual must be prepared with simplicity and dignity.”

Edna Dean Proctor wrote an ode for the event, and “There was also an oration suitable for declamation.” Bellamy held that “Of course, the nub of the program was to be the raising of the flag, with a salute to the flag recited by the pupils in unison.” He found “There was not a satisfactory enough form for this salute. The Balch salute, which ran, “I give my heart and my hand to my country, one country, one language, one flag,” seemed to him too juvenile and lacking in dignity.” After working on the idea with Upham, Bellamy concluded, “It was my thought that a vow of loyalty or allegiance to the flag should be the dominant idea. I especially stressed the word ‘allegiance’. … Beginning with the new word allegiance, I first decided that ‘pledge’ was a better school word than ‘vow’ or ‘swear’; and that the first person singular should be used, and that ‘my’ flag was preferable to ‘the.'” Bellamy considered the words “country, nation, or Republic,” choosing the last as “it distinguished the form of government chosen by the founding fathers and established by the Revolution. The true reason for allegiance to the flag is the Republic for which it stands.” Bellamy then reflected on the sayings of Revolutionary and Civil War figures, and concluded “all that pictured struggle reduced itself to three words, one Nation indivisible.”

Bellamy considered the slogan of the French Revolution, Liberté, égalité, fraternité (“liberty, equality, fraternity”), but held that “fraternity was too remote of realization, and … [that] equality was a dubious word.” Concluding “Liberty and justice were surely basic, were undebatable, and were all that any one Nation could handle. If they were exercised for all. they involved the spirit of equality and fraternity.”

After being reviewed by Upham and other members of The Youth’s Companion, the Pledge was approved and put in the official Columbus Day program. Bellamy noted that, “In later years the words ‘to my flag’ were changed to ‘to the flag of the United States of America’ because of the large number of foreign children in the schools.” Bellamy disliked the change, as “it did injure the rhythmic balance of the original composition.”

In 1906, The Daughters of the American Revolution’s magazine, The American Monthly, listed the “formula of allegiance” as being the Balch Pledge of Allegiance, which reads:

I pledge allegiance to my flag, and the republic for which it stands. I pledge my head and my heart to God and my country. One country, one language and one flag.

In subsequent publications of the Daughters of the American Revolution, such as in 1915’s “Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth Continental Congress of the Daughters of the American Revolution” and 1916’s annual “National Report,” the Balch Pledge, listed as official in 1906, is now categorized as “Old Pledge” with Bellamy’s version under the heading “New Pledge.” However, the “Old Pledge” continued to be used by other organizations until the National Flag Conference established uniform flag procedures in 1923.

In 1923, the National Flag Conference called for the words “my Flag” to be changed to “the Flag of the United States,” so that new immigrants would not confuse loyalties between their birth countries and the US. The words “of America” were added a year later. Congress officially recognized the Pledge for the first time, in the following form, on June 22, 1942:

I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America, and to the Republic for which it stands, one Nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

In 1940, the Supreme Court, in Minersville School District v. Gobitis, ruled that students in public schools, including the respondents in that case — Jehovah’s Witnesses who considered the flag salute to be idolatry — could be compelled to swear the Pledge. In 1943, in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, the Supreme Court reversed its decision. Justice Robert H. Jackson, writing for the 6 to 3 majority, went beyond simply ruling in the precise matter presented by the case to say that public school students are not required to say the Pledge on narrow grounds, and asserted that such ideological dogmata are antithetical to the principles of the country, concluding with:

If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein. If there are any circumstances which permit an exception, they do not now occur to us.

In a later case, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals held that students are also not required to stand for the Pledge.

Louis Albert Bowman, an attorney from Illinois, was the first to suggest the addition of “under God” to the pledge. The National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution gave him an Award of Merit as the originator of this idea. He spent his adult life in the Chicago area and was chaplain of the Illinois Society of the Sons of the American Revolution. At a meeting on February 12, 1948, he led the society in reciting the pledge with the two words “under God” added. He said that the words came from Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. Although not all manuscript versions of the Gettysburg Address contain the words “under God”, all the reporters’ transcripts of the speech as delivered do, as perhaps Lincoln may have deviated from his prepared text and inserted the phrase when he said “that the nation shall, under God, have a new birth of freedom.” Bowman repeated his revised version of the Pledge at other meetings.

In 1951, the Knights of Columbus, the world’s largest Catholic fraternal service organization, also began including the words “under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance. In New York City, on April 30, 1951, the board of directors of the Knights of Columbus adopted a resolution to amend the text of their Pledge of Allegiance at the opening of each of the meetings of the 800 Fourth Degree Assemblies of the Knights of Columbus by addition of the words “under God” after the words “one nation.” Over the next two years, the idea spread throughout Knights of Columbus organizations nationwide. On August 21, 1952, the Supreme Council of the Knights of Columbus at its annual meeting adopted a resolution urging that the change be made universal, and copies of this resolution were sent to the President, the Vice President (as Presiding Officer of the Senate), and the Speaker of the House of Representatives. The National Fraternal Congress meeting in Boston on September 24, 1952, adopted a similar resolution upon the recommendation of its president, Supreme Knight Luke E. Hart. Several State Fraternal Congresses acted likewise almost immediately thereafter. This campaign led to several official attempts to prompt Congress to adopt the Knights of Columbus policy for the entire nation. These attempts were eventually a success.

At the suggestion of a correspondent, Representative Louis C. Rabaut (D-Mich.), of Michigan sponsored a resolution to add the words “under God” to the Pledge in 1953.

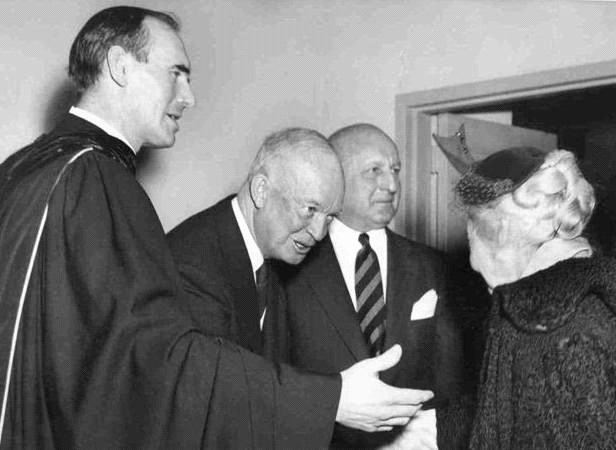

Before February 1954, no endeavor to get the pledge officially amended had succeeded. The final successful push came from George MacPherson Docherty. Some American presidents honored Lincoln’s birthday by attending services at the church Lincoln attended, New York Avenue Presbyterian Church by sitting in Lincoln’s pew on the Sunday nearest February 12. On February 7, 1954, with President Eisenhower sitting in Lincoln’s pew, the church’s pastor, George MacPherson Docherty, delivered a sermon based on the Gettysburg Address entitled “A New Birth of Freedom.” He argued that the nation’s might lay not in arms but rather in its spirit and higher purpose. He noted that the Pledge’s sentiments could be those of any nation: “There was something missing in the pledge, and that which was missing was the characteristic and definitive factor in the American way of life.” He cited Lincoln’s words “under God” as defining words that set the US apart from other nations.

President Eisenhower had been baptized a Presbyterian very recently, just a year before. He responded enthusiastically to Docherty in a conversation following the service. Eisenhower acted on his suggestion the next day and on February 8, 1954, Rep. Charles Oakman (R-Mich.), introduced a bill to that effect. Congress passed the necessary legislation and Eisenhower signed the bill into law on Flag Day, June 14, 1954. Eisenhower said:

From this day forward, the millions of our school children will daily proclaim in every city and town, every village and rural school house, the dedication of our nation and our people to the Almighty…. In this way we are reaffirming the transcendence of religious faith in America’s heritage and future; in this way we shall constantly strengthen those spiritual weapons which forever will be our country’s most powerful resource, in peace or in war.

The phrase “under God” was incorporated into the Pledge of Allegiance on June 14, 1954, by a Joint Resolution of Congress amending § 4 of the Flag Code enacted in 1942.

On October 6, 1954, the National Executive Committee of the American Legion adopted a resolution, first approved by the Illinois American Legion Convention in August 1954, which formally recognized the Knights of Columbus for having initiated and brought forward the amendment to the Pledge of Allegiance.

Even though the movement behind inserting “under God” into the pledge might have been initiated by a private religious fraternity and even though references to God appear in previous versions of the pledge, author Kevin M. Kruse asserts that this movement was an effort by corporate America to instill in the minds of the people that capitalism and free enterprise were heavenly blessed. Kruse acknowledges the insertion of the phrase was influenced by the push-back against atheistic communism during the Cold War, but argues the longer arc of history shows the conflation of Christianity and capitalism as a challenge to the New Deal played the larger role.

Requiring or promoting of the Pledge on the part of the government has continued to draw criticism and legal challenges on several grounds.

One objection is that a democratic republic built on freedom of dissent should not require its citizens to pledge allegiance to it, and that the First Amendment to the United States Constitution protects the right to refrain from speaking or standing, which itself is also a form of speech in the context of the ritual of pledging allegiance. Another objection is that the people who are most likely to recite the Pledge every day, small children in schools, cannot really give their consent or even completely understand the Pledge they are making. Another criticism is that a government requiring or promoting the phrase “under God” violates protections against the establishment of religion guaranteed in the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

In 2004, linguist Geoffrey Nunberg said the original supporters of the addition thought that they were simply quoting Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, but to Lincoln and his contemporaries, “under God” meant “God willing”, so they would have found its use in the Pledge of Allegiance grammatically incorrect and semantically odd.

Swearing of the Pledge is accompanied by a salute. An early version of the salute, adopted in 1887, known as the Balch Salute, which accompanied the Balch pledge, instructed students to stand with their right hand outstretched toward the flag, the fingers of which are then brought to the forehead, followed by being placed flat over the heart, and finally falling to the side.

![[url=https://flic.kr/p/28r3f5F][img]https://farm2.staticflickr.com/1767/42946539911_306798f678_o.jpg[/img][/url][url=https://flic.kr/p/28r3f5F]pledge-of-allegiance-1[/url] by [url=https://www.flickr.com/photos/am-jochim/]Mark Jochim[/url], on Flickr](https://farm2.staticflickr.com/1767/42946539911_306798f678_o.jpg)

In 1892, Francis Bellamy created what was known as the Bellamy salute. It started with the hand outstretched toward the flag, palm down, and ended with the palm up. Because of the similarity between the Bellamy salute and the Nazi salute, which was adopted in Germany later, the U.S. Congress stipulated that the hand-over-the-heart gesture as the salute to be rendered by civilians during the Pledge of Allegiance and the national anthem in the United States would be the salute to replace the Bellamy salute. Removal of the Bellamy salute occurred on December 22, 1942, when Congress amended the Flag Code language first passed into law on June 22, 1942. Attached to bills passed in Congress in 2008 and then in 2009 (Section 301(b)(1)of title 36, United States Code), language was included which authorized all active duty military personnel and all veterans in civilian clothes to render a proper hand salute during the raising and lowering of the flag, when the colors are presented, and during the National Anthem.

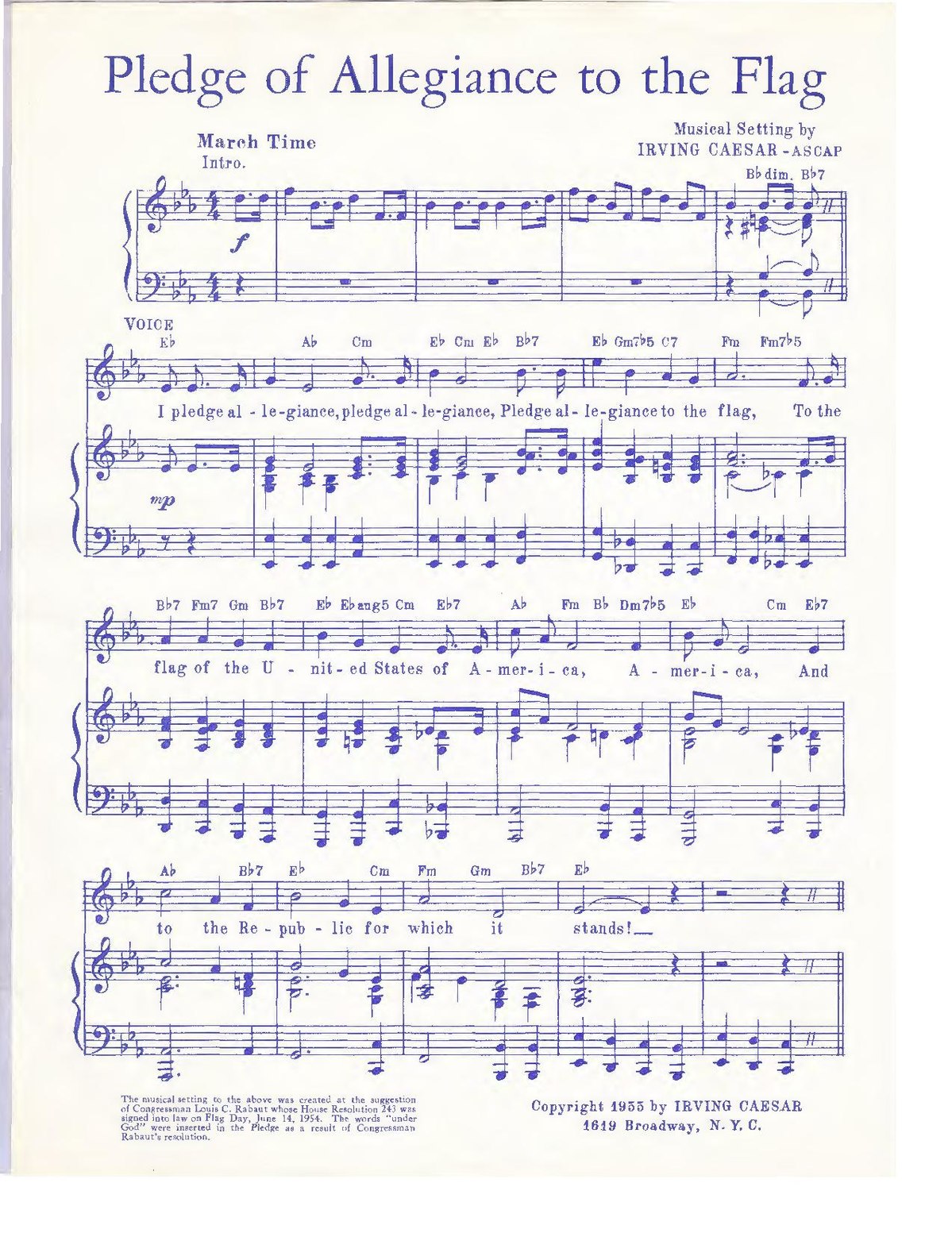

A musical setting for “The Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag” was created by Irving Caesar, at the suggestion of Congressman Louis C. Rabaut whose House Resolution 243 to add the phrase “under God” was signed into law on Flag Day, June 14, 1954.

The composer, Irving Caesar, wrote and published over 700 songs in his lifetime. Dedicated to social issues, he donated all rights of the musical setting to the U.S. government, so that anyone can perform the piece without owing royalties.

It was sung for the first time on the floor of the House of Representatives on Flag Day, June 14, 1955 by the official Air Force choral group the “Singing Sergeants”. A July 29, 1955 House and Senate resolution authorized the U.S. Government Printing Office to print and distribute the song sheet together with a history of the pledge.

Other musical versions of the Pledge have since been copyrighted, including by Beck (2003), Lovrekovich (2002 and 2001), Roton (1991), Fijol (1986), and Girardet (1983).

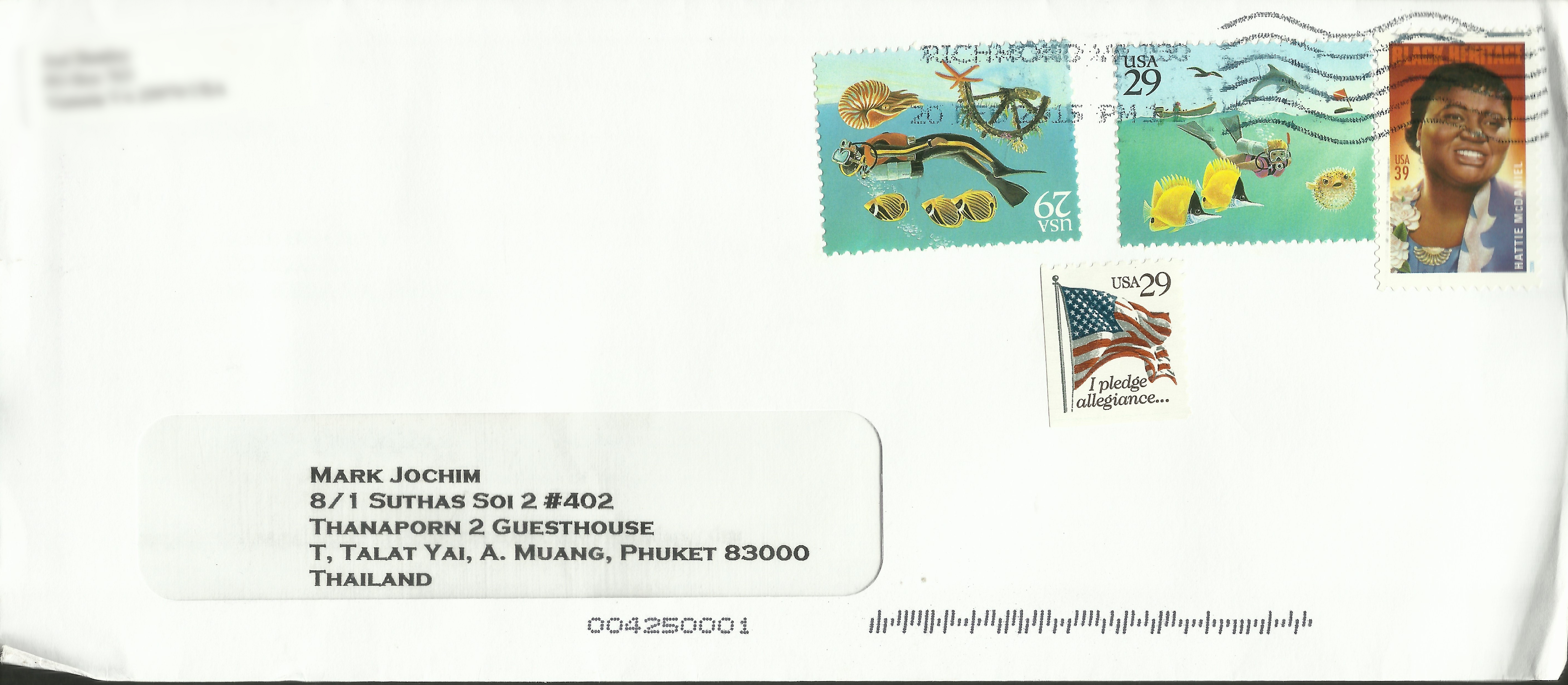

The centennial of the Pledge of Allegiance was honored on a 29-cent stamp issued by the U.S. Postal Service on September 8, 1992, in Rome, New York (Scott #2593). Designed by Lou Nolan, the stamps were printed on the photogravure press by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, perforated 9.8 on 2 or 3 sides. The definitive size Pledge of Allegiance stamp was available in both a ten-stamp and a twenty-stamp booklet with a total of 22,274,000 copies printed. On April 8, 1993, this stamp was reissued with a red “USA” and 29¢ denomination (Scott #2594). This was printed by Stamp Venturers for KCS Industries in a quantity of 152,754,000.

One thought on “The U.S. Pledge of Allegiance”