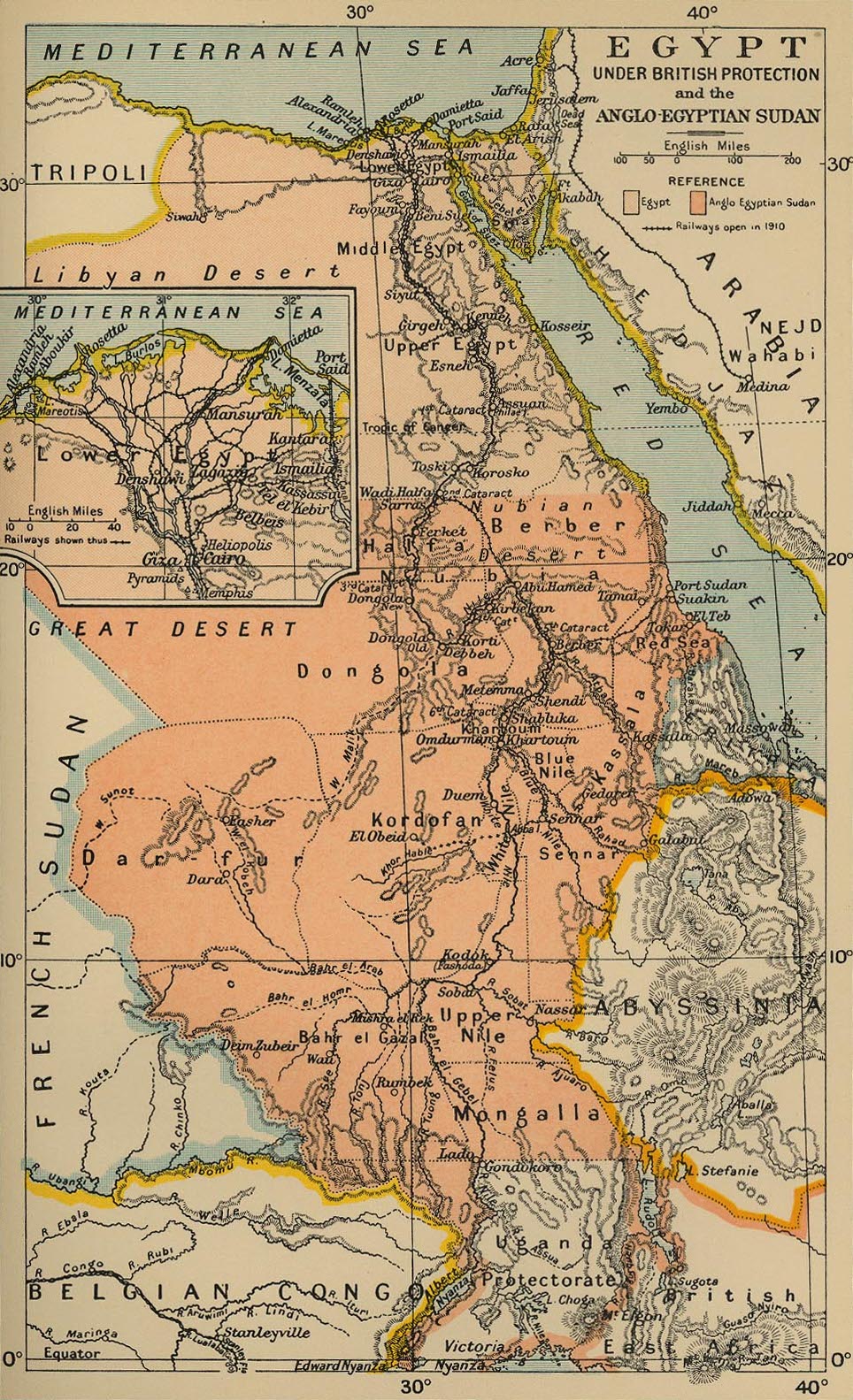

The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (السودان الإنجليزي المصري — as-Sūdān al-Inglīzī al-Maṣrī) was a condominium of the United Kingdom and Egypt in the eastern Sudan region of northern Africa between 1899 and 1956, but in practice the structure of the condominium ensured full British control over the Sudan with Egypt having local influence instead. It attained independence as the Republic of the Sudan, which since 2011 has been split into Sudan and South Sudan.

The history of Sudan goes back to the Pharaonic period, witnessing the kingdom of Kerma (circa 2500 BC-1500 BC), the subsequent rule of the Egyptian New Kingdom (circa 1500 BC-1070 BC) and the rise of the kingdom of Kush (circa 785 BC-350 AD), which would in turn control Egypt itself for nearly a century. After the fall of Kush, the Nubians formed the three Christian kingdoms of Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia, with the latter two lasting until around 1500. Since the 7th century eastern Sudan was settled by Muslim Arabs, who would eventually push into the Nile Valley and the regions west of it in the 14th and 15th centuries. From the 16th-19th centuries, central and eastern Sudan were dominated by the Funj sultanate, while Darfur ruled the west and the Ottomans the far north. This period saw extensive Islamization and Arabization.

Until 1814, Egypt itself was nominally part of the Ottoman Empire. During the 19th century it gradually expanded its control of the Sudan as far south as the Great Lakes region. From 1820 to 1874, the entirety of Sudan was conquered by the Muhammad Ali dynasty. Between 1881 and 1885, the harsh Egyptian reign was eventually met with a successful revolt led by the self-proclaimed Mahdi Muhammad Ahmad, resulting in the establishment of the Caliphate of Omdurman. In 1882, the British invaded Egypt. Egypt became a de facto protectorate of Britain and together British and Egyptian forces gradually re-conquered the Sudan. In 1899, they formally agreed to establish a joint protectorate: Egypt on the basis of its previous claims and Britain by right of conquest.

Between 1914 and 1922, Egypt and thus the Sudan were formally a part of the British Empire. After Egyptian independence in 1922, Britain gradually assumed more control of the condominium, edging out Egypt almost completely by 1924. Increasing Egyptian dissatisfaction with this arrangement came to a head after the overthrow of the Egyptian monarch in 1952. In 1953, Britain granted Sudan self-government. Independence was proclaimed on January 1, 1956, the nation becoming the Republic of the Sudan ( جمهورية السودان — Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān).

In 1820, the army of Egyptian wāli Muhammad Ali Pasha, commanded by his son Ismail Pasha, gained control of Sudan. The region had longstanding linguistic, cultural, religious, and economic ties to Egypt and had been partially under the same government at intermittent periods since the times of the pharaohs. Muhammad Ali was aggressively pursuing a policy of expanding his power with a view to possibly supplanting the Ottoman Empire (to which he technically owed fealty) and saw Sudan as a valuable addition to his Egyptian dominions. During his reign and that of his successors, Egypt and Sudan came to be administered as one political entity, with all ruling members of the Muhammad Ali dynasty seeking to preserve and extend the “unity of the Nile Valley”. This policy was expanded and intensified most notably by Muhammad Ali’s grandson, Ismail Pasha, under whose reign most of the remainder of modern-day Sudan was conquered.

With the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, Egypt and Sudan’s economic and strategic importance increased enormously, attracting the imperial attentions of the Great Powers, particularly the United Kingdom. Ten years later in 1879, the immense foreign debt of Ismail Pasha’s government served as the pretext for the Great Powers to force his abdication and replacement by his son Tewfik Pasha. The manner of Tewfik’s ascension at the hands of foreign powers greatly angered Egyptian and Sudanese nationalists who resented the ever-increasing influence of European governments and merchants in the affairs of the country. The situation was compounded by Tewfik’s perceived corruption and mismanagement and ultimately culminated in the ‘Urabi Revolt. With the survival of his throne in dire jeopardy, Tewfik appealed for British assistance. In 1882, at Tewfik’s invitation, the British bombarded Alexandria, Egypt’s and Sudan’s primary seaport, and subsequently invaded the country. British forces overthrew the Urabi government in Cairo and proceeded to occupy the rest of Egypt and Sudan in 1882. Though officially the authority of Tewfik had been restored, in reality the British largely took control of Egyptian and Sudanese affairs until 1932.

Tewfik’s acquiescence to British occupation as the price for securing the monarchy was deeply detested by many throughout Egypt and Sudan. With the bulk of British forces stationed in northern Egypt, protecting Cairo, Alexandria, and the Suez Canal, opposition to Tewfik and his European protectors was stymied in Egypt. In contrast, the British military presence in Sudan was comparatively limited and eventually revolt broke out. The rebellion in Sudan, led by the Sudanese religious leader Muhammad ibn Abdalla, the self-proclaimed Mahdi (Guided One), was both political and religious. Abdalla wished not only to expel the British, but to overthrow the monarchy, viewed as secular and Western-leaning, and replace it with a pure Islamic government. Whilst primarily a Sudanese figure, Abdalla even attracted the support of some Egyptian nationalists and caught Tewfik and the British off-guard. The revolt culminated in the fall of Khartoum and the death of the British General Charles George Gordon (Gordon of Khartoum) in 1885. Tewfik’s forces and those of the United Kingdom were forced to withdraw from almost all of Sudan with Abdalla establishing a theocratic state.

Abdalla’s religious government imposed traditional Islamic laws upon Sudan and stressed the need to continue the armed struggle until the British had been completely expelled from the country and all of Egypt and Sudan was under his Mahdiya. Though he died six months after the fall of Khartoum, Abdalla’s call was fully echoed by his successor, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, who invaded Ethiopia in 1887 and penetrated as far as Gondar, and the remainder of northern Sudan and Egypt in 1889. This invasion was halted by Tewfik’s forces, and was followed later by withdrawal from Ethiopia. Abdullahi wrecked virtually all of the previous Turkish and Fung administrative systems and gravely weakened Sudanese tribal unities. From 1885 to 1898 the population of Sudan collapsed from eight to three million due to war, famine, disease and persecution.

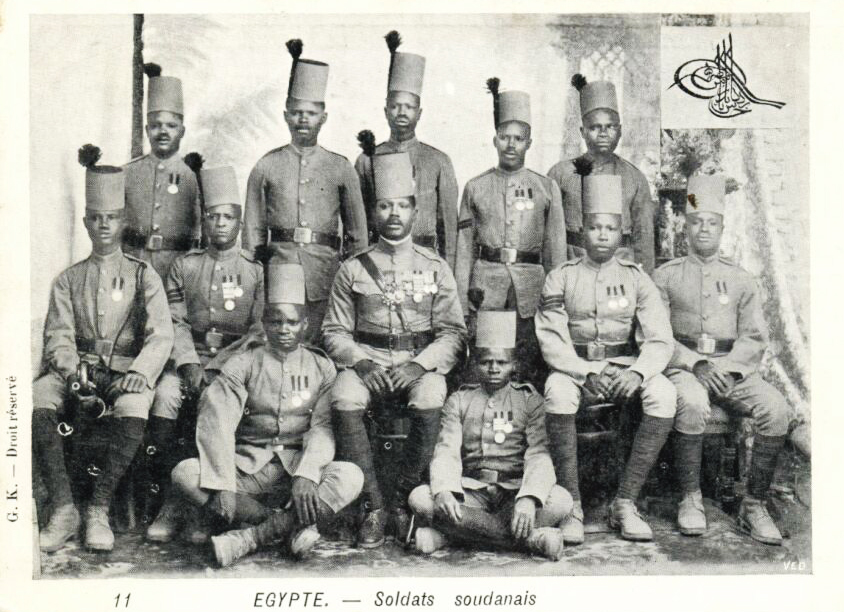

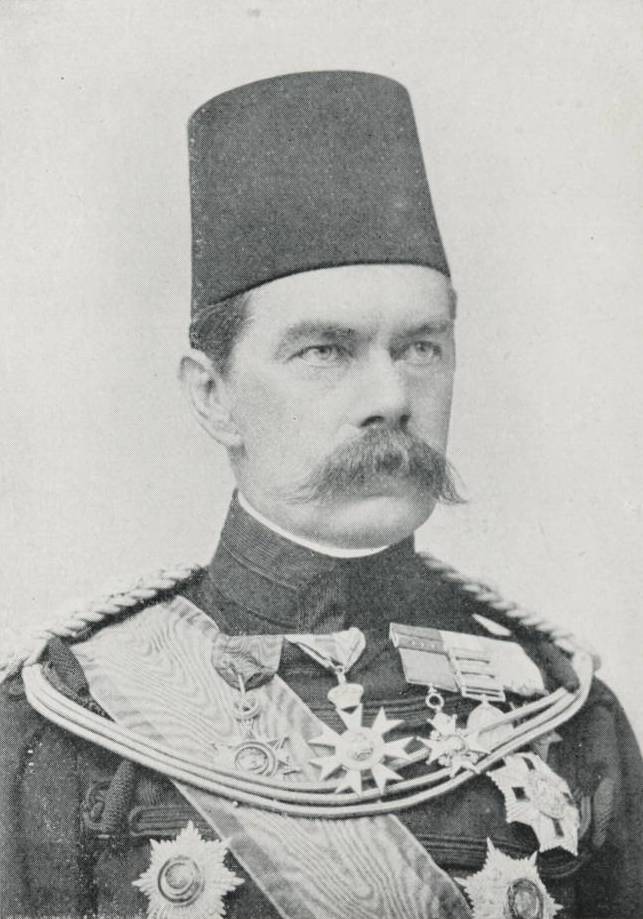

After a series of Mahdist defeats, Tewfik’s son and successor, Abbas II, and the British decided to re-establish control over Sudan. Leading a joint Egyptian-British force, Kitchener led military campaigns from 1896 to 1898. Kitchener’s campaigns culminated in the Battle of Atbara and the Battle of Omdurman. Exercising the leverage which their military superiority provided, the British forced Abbas to accept British control in Sudan. Whereas British influence in Egypt was officially advisory (though in reality it was far more direct), the British insisted that their role in Sudan be formalized. Thus, an agreement was reached in 1899 establishing Anglo-Egyptian rule (a condominium), under which Sudan was to be administered by a governor-general appointed by Egypt with British consent. In reality, much to the revulsion of Egyptian and Sudanese nationalists, Sudan was effectively administered as a British imperial possession. Pursuing a policy of divide and rule, the British were keen to reverse the process, started under Muhammad Ali, of uniting the Nile Valley under Egyptian leadership, and sought to frustrate all efforts to further unite the two countries. During World War I, the British invaded and incorporated Darfur into the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan in 1916.

This policy was internalized within Sudan itself, with the British determined to exacerbate differences and frictions between Sudan’s numerous different ethnic groups. From 1924 onwards, the British essentially divided Sudan into two separate territories–a predominantly Muslim Arabic-speaking north, and a predominantly Animist and Christian south, where the use of English was encouraged by Christian missionaries, whose main role was instructional.

The continued British occupation of Sudan fueled an increasingly strident nationalist backlash in Egypt, with Egyptian nationalist leaders determined to force Britain to recognize a single independent union of Egypt and Sudan. With the formal end in 1914 of the legal fiction of Ottoman sovereignty, Hussein Kamel was declared Sultan of Egypt and Sudan, as was his brother Fuad I who succeeded him. The insistence of a single Egyptian-Sudanese state persisted when the Sultanate was re-titled the Kingdom of Egypt and Sudan, but the British continued to frustrate these efforts.

The failure of the government in Cairo to end the British occupation led to separate efforts for independence in Sudan itself, the first of which was led by a group of Sudanese military officers known as the White Flag League in 1924. The group was led by first lieutenant Ali Abd al Latif and first lieutenant Abdul Fadil Almaz. The latter led an insurrection of the military training academy, which ended in their defeat and the death of Almaz after the British army blew up the military hospital where he was garrisoned. This defeat was (allegedly) partially the result of the Egyptian garrison in Khartoum North not supporting the insurrection with artillery as was previously promised.

Even when the British ended their occupation of Egypt in 1936 (with the exception of the Suez Canal Zone), they maintained their forces in Sudan. Successive governments in Cairo, repeatedly declaring their abrogation of the condominium agreement, declared the British presence in Sudan to be illegitimate, and insisted on full British recognition of King Farouk as “King of Egypt and Sudan”, a recognition which the British were loath to grant; not least because Farouk was secretly negotiating with Mussolini for an Italian invasion. The defeat of this damaging démarche of 1940 for Anglo-Egyptian relations helped to turn the tide of the Second World War.

It was the Egyptian Revolution of 1952 which finally set a series of events in motion which would eventually end the British and Egyptian occupation of Sudan. Having abolished the monarchy in 1953, Egypt’s new leaders, Muhammad Naguib, who was raised as a child of an Egyptian army officer in Sudan, and Gamal Abdel Nasser, believed the only way to end British domination in Sudan was for Egypt itself to officially abandon its sovereignty over Sudan. Since the British claim to control in Sudan theoretically depended upon Egyptian sovereignty, the revolutionaries calculated that this tactic would leave the UK with no option but to withdraw. In addition Nasser knew that it would be problematic for Egypt to govern the impoverished Sudan. In October 1954, the governments of Egypt and the UK signed a treaty guaranteeing Sudanese independence. On January 1, 1956, the date agreed between the Egyptian and British governments, Sudan became an independent sovereign state, ending its nearly 136-year union with Egypt and its 56-year occupation by the British.

The first post offices to be opened in Sudan were in 1867 at Suakin and Wadi Halfa; in 1873 at Dongola, Berber and Khartoum; and in 1877 at Sennar, Karkouk, Fazoglu, Elkedaref, El Obeid, Al-Fasher and Fashoda (now Kodok).

The Mahdist revolt, which began in 1881, resulted in all Egyptian post offices being closed by 1884. It culminated in the fall of Khartoum and the death of the British governor General Gordon (Gordon of Khartoum) in 1885. The Egyptians and British withdrew their forces from Sudan and the country was left with no postal service until the reconquest of Sudan began in 1896. When the campaign started in March 1896, postal service was made available to the troops but no stamps were used.

Until the issue of Sudan stamps in 1897 the available stamps were Egyptian stamps. The amount of mail was small and only a few stamps were used. Between March and July 1885 2½-pence and 5-pence British postage stamps were used in Suakin. Indian stamps are also known to have been used in the same area, postmarked Sawakin or Souakin, between 1884 and 1899.

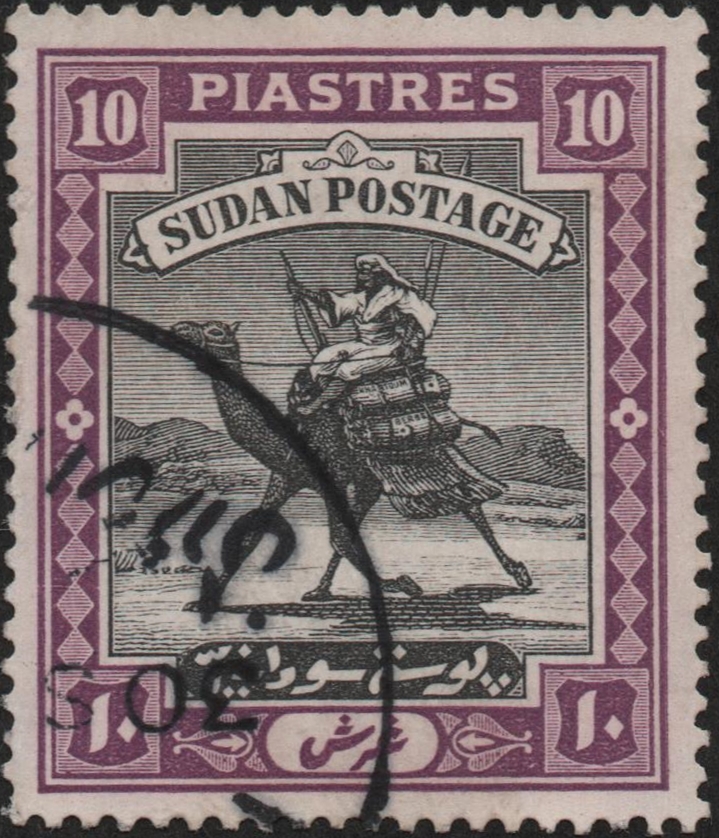

On March 1, 1897, contemporary Egyptian postage stamps, overprinted SOUDAN in French and Arabic, were made available in the post offices. The values which appeared were 1, 2, 3 and 5 milliemes and 1, 2, 5 and 10 piastres. The overprinting was done at the Imprimerie Nationale, Boulaq, Cario, Egypt.

In 1898, the British achieved victory at the Battle of Omburdman finally ending the barbaric rule of the Mahidists. General Sir Herbert Kitchener was appointed the Commander of the Anglo-Egyptian Army with orders to restore peace and the rule of law.. The country was then jointly administered by Great Britain and Egypt, the reason that Sudan’s stamps do not portray a British monarch.

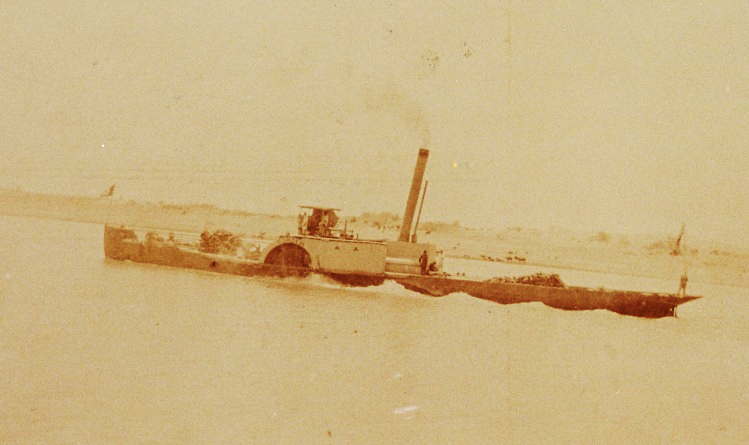

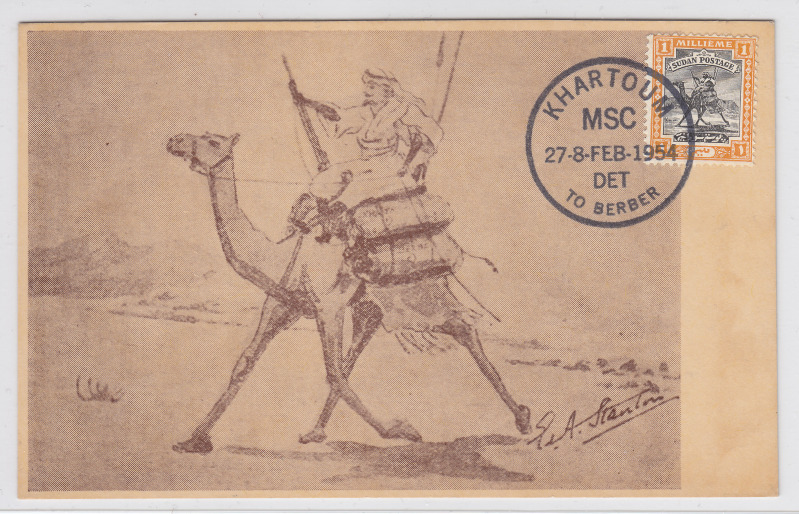

One of Kitchener’s first tasks was to re-introduce a workable postal system which included postage stamps. A professional artist was asked to submit ideas for a new design, one of which featured the Abu Simbel temple in southern Egypt. The cost of 25 guineas was considered to be too high. Early the previous year, Kitchener had made a routine visit to troops stationed at Korti where he met with a Captain Edward Stanton whose job was to draw military maps. Such was the wilderness and boredom of the task that Stanton had “doodled” sketches in the margins. During this inspection visit to Korti, Kitchener sought him out and instructed him to come up with a design for stamps, announcing that he would be back in five day’s time.

It was the arrival of the regimental mail by camel rather than the normal steamer that gave Stanton the idea for his iconic stamp design. Using a local tribesman dressed in war kit as a model, and the addition of two leather carriers filled with straw as substitutes for mail bags, he produced a watercolor sketch of the “postman”. He even inscribed a minute Star and Crescent on the outside of the dummy mail bags along with the names of two towns — Khartoum and Berber — although both locations were still in enemy hands. The backdrop of desert and mountains completed what was to become an iconic stamp design, the “Sudan Camel Postman”.

Kitchener approved the design and on June 6, 1897, the sketch was dispatched to London’s Thomas De La Rue, the leading stamp printers of the time, with instructions to commence work on a set of eight values, and leaving most of the detail to them. Clearly, De La Rue liked the design too and one of their top engravers, W. Turner, produced a remarkably exact reduction as the master die, even including the Berber and Khartoum inscriptions, to Stanton’s later delight. In fact, De La Rue are on record as regarding the ‘Camel Postman’ design as the most satisfactory in all their long history of stamp production.

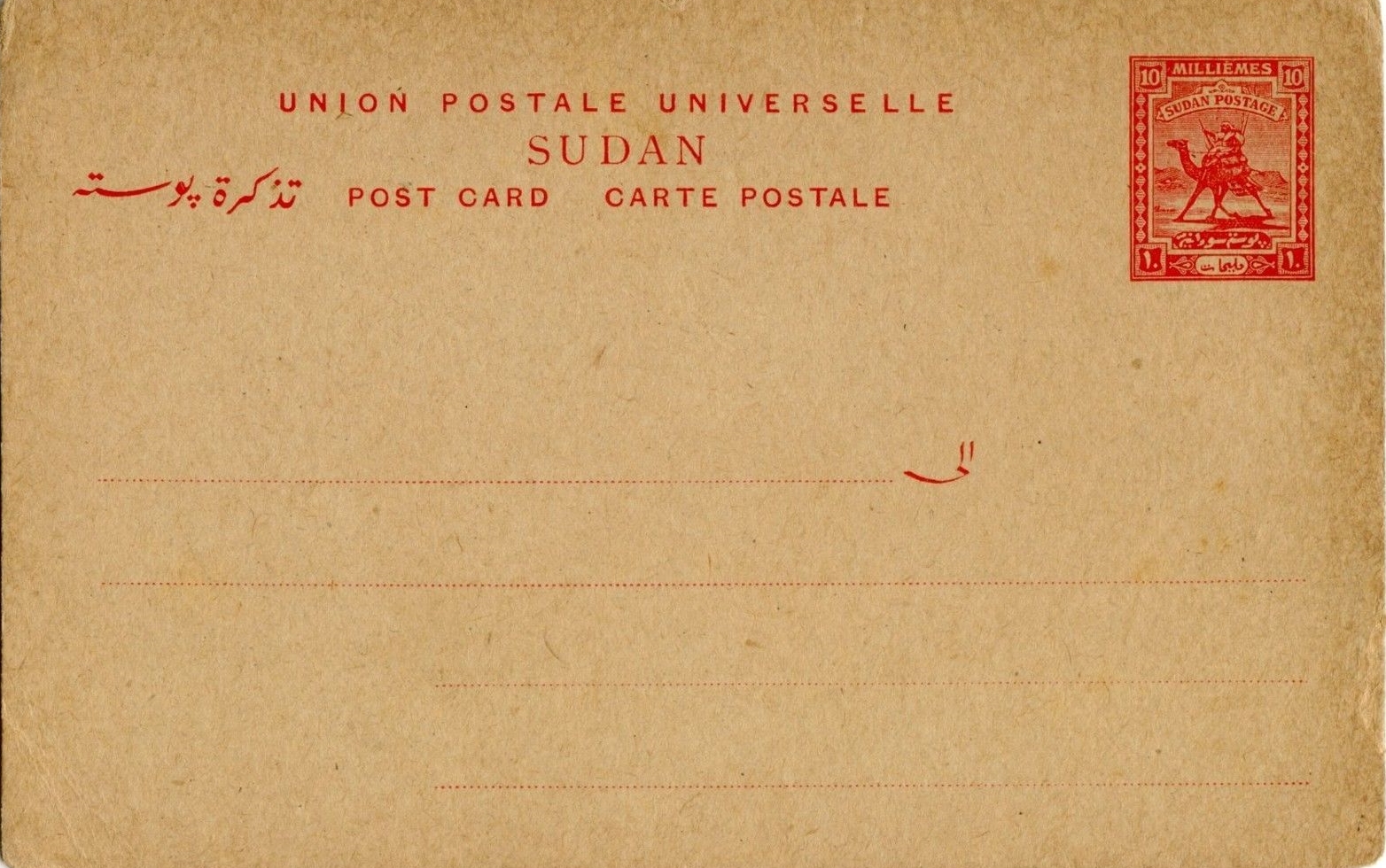

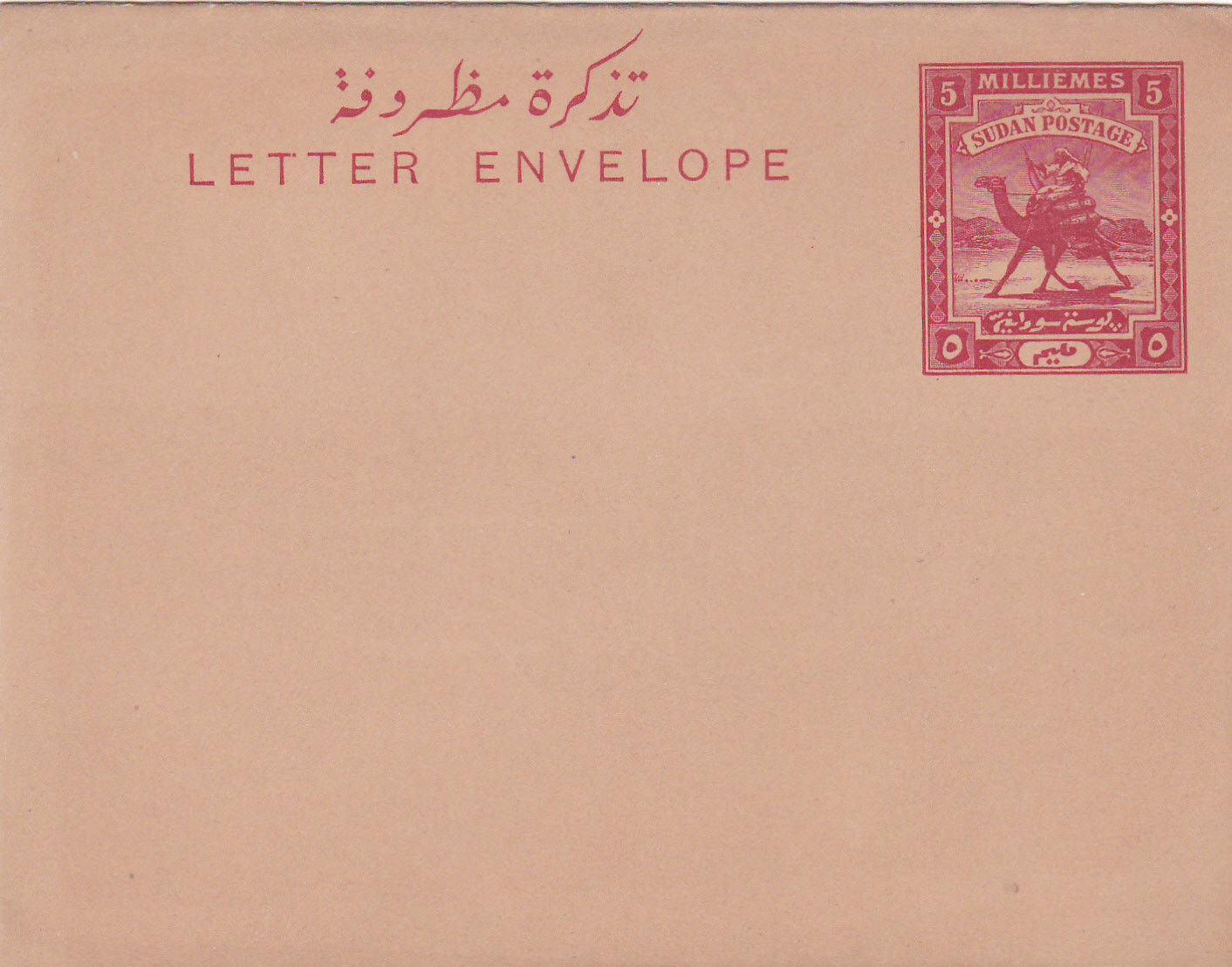

The first set was issued on March 1, 1898, by which time Berber had been captured, with Khartoum falling six months later. De La Rue printed the eight different values on medium white wove paper using a Rosette watermark. This was changed in 1902 to the Islamic Star and Crescent in response to strong objection to “kissing” the symbol of the Christian Cross every time a stamp was licked before being stuck to an envelope.

Stanton requested a set of the new eight definitive stamps that were issued in March 1898, and Kitchener’s responded that the Captain should pay the face value price of four shillings and sixpence should he require to own them. Stanton did indeed receive a full set and a personal letter from the General himself. Copies of the original illustration and the autographed set are held in a museum in Khartoum.

Colonel Stanton, (the rank with which he retired) a modest man, wrote in 1947:

The fact of having been more or less accidentally called upon to design the Camel Stamp hardly justifies my intrusion into the realms of Philately, and rush into print where angels (if there are any amongst philatelists) fear to make themselves known.

The design came to symbolize the country. Not only did the design feature on the general issue definitive postage stamps but handstamps were applied for the government and military and even used in the postal training school overprinted SCHOOL. There was a variety of postal stationery featuring the Camel Postman as well. Sudan did not issue anything but ‘Camel postmen’ stamps until 1931, when supplementary airmail stamps were issued, and the design did not finally lose its pre-eminence until a new pictorial set appeared in 1951. Even then, Stanton’s original concept was retained for the top value, which remained current until long after Sudan became independent in 1956. Meanwhile, in 1948 there had been two commemorative issues, one marking the Camel Postman golden jubilee, and the other for the opening of the Legislative Assembly. Both featured the same, by now inevitable, image.

I have only just received my first Camel Postman stamps, eight of the sixteen stamps released by Sudan on January 1, 1948 (Scott #79-94). These stamps were printed by typography, watermarked with SG (Sudan Government), perforated 14, and had the Arabic inscription at the base changed from Posta Sudaniye to Berid es-Sudan. Scott #92 is the 10-piastre denomination, printed in deep rose lilac and black. I hope to obtain more of these iconic stamps in the near future. For a great deal of information, I recommend reading through this thread on the StampBoards forum which includes several very informative exhibition pages.

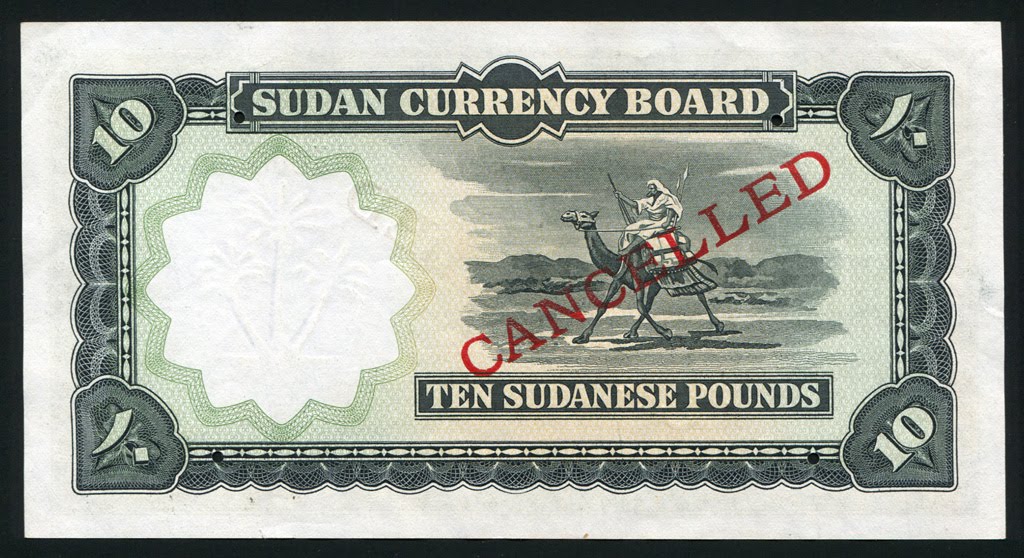

The Camel Postman was later chosen to adorn the back of Sudan’s first banknotes. These notes were printed by Waterlow and Sons of London and were to be issued under the authority of the Government of Sudan. However, there was a delay in the issue of the notes, due to difficulties with Sudan and Egypt negotiating the withdrawal of Egyptian currency, which was then circulating in Sudan. By the time negotiations were complete, the Sudan Currency Board had been established and there had been a change of government in Sudan. Because the signature of the previous Prime Minister appeared on the yet-to-be-issued notes, the new Prime Minister ordered the banknotes to be destroyed. A new series of banknotes was subsequently prepared by Thomas de la Rue and issued in April 1957 by the Sudan Currency Board.

In 1960, the Bank of Sudan was established and it soon issued banknotes under its own authority, having initially used the notes of the Currency Board. The design of the new notes was similar to those issued by the Currency Board, with only slight changes to the text. These notes remained in circulation until 1970 when the Bank of Sudan’s second series of notes was introduced. The iconic image was also featured on on coins issued by Sudan from 1956 to 1970.

![[url=https://flic.kr/p/2aJDBfu][img]https://farm2.staticflickr.com/1874/44458534012_0a0457c8fd_o.png[/img][/url][url=https://flic.kr/p/2aJDBfu]Sudan coin with camel postman[/url] by [url=https://www.flickr.com/photos/am-jochim/]Mark Jochim[/url], on Flickr](https://farm2.staticflickr.com/1874/44458534012_0a0457c8fd_o.png)

Kitchener became Governor-General of the Sudan in September 1898, and began a program of restoring good governance. The program had a strong foundation, based on education at Gordon Memorial College as its centerpiece — and not simply for the children of the local elites, for children from anywhere could apply to study. He ordered the mosques of Khartoum rebuilt, instituted reforms which recognized Friday — the Muslim holy day — as the official day of rest, and guaranteed freedom of religion to all citizens of the Sudan. He attempted to prevent evangelical Christian missionaries from trying to convert Muslims to Christianity. He was soon made Lord Kitchener of Khartoum, becoming a qualifying peer and of mid-rank as an Earl.

Kitchener would go on to win notoriety for his imperial campaigns, most especially his scorched earth policy against the Boers and his establishment of concentration camps during the Second Boer War. His term as Commander-in-Chief of the Army in India saw him quarrel with another eminent proconsul, the Viceroy Lord Curzon, who eventually resigned. Kitchener then returned to Egypt as British Agent and Consul-General (de facto administrator). In 1914, at the start of the First World War, Kitchener became Secretary of State for War, a Cabinet Minister.

One of the few to foresee a long war, lasting for at least three years, and with the authority to act effectively on that perception, Kitchener organized the largest volunteer army that Britain had seen, and oversaw a significant expansion of materials production to fight on the Western Front. Despite having warned of the difficulty of provisioning for a long war, he was blamed for the shortage of shells in the spring of 1915 — one of the events leading to the formation of a coalition government — and stripped of his control over munitions and strategy.

On June 5, 1916, Kitchener was making his way to Russia to attend negotiations, on HMS Hampshire, when it struck a German mine 1.5 miles (2.4 km) west of the Orkney Islands, Scotland, and sank. Kitchener was among 737 who died.

One thought on “Anglo-Egyptian Sudan & Its Iconic Camel Postman”