On March 2, 1933, the film King Kong opened at New York’s Radio City Music Hall to rave reviews. Directed and produced by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, the screenplay by James Ashmore Creelman and Ruth Rose was developed from an idea conceived by Cooper and Edgar Wallace. It stars Fay Wray, Bruce Cabot and Robert Armstrong. It has been ranked by Rotten Tomatoes as the greatest horror film of all time and the thirty-third greatest film of all time.

The film tells of a huge, ape-like creature dubbed Kong who perishes in an attempt to possess a beautiful young woman (Wray). King Kong is especially noted for its stop-motion animation by Willis O’Brien and a groundbreaking musical score by Max Steiner. In 1991, it was deemed “culturally, historically and aesthetically significant” by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry. A sequel quickly followed with Son of Kong (also released in 1933), with several more films made in the following decades.

Before King Kong entered production, a long tradition of jungle films existed, and, whether drama or documentary, such films (for example Stark Mad) generally adhered to a narrative pattern that followed an explorer or scientist into the jungle to test a theory only to discover some monstrous aberration in the undergrowth. In these films, scientific knowledge could be subverted at any time, and it was this that provided the genre with its vitality, appeal, and endurance.

In the early 20th century, few zoos had primate exhibits so there was popular demand to see them on film. At the turn of the 20th century, the Lumière Brothers sent film documentarians to places westerners had never seen, and Georges Méliès utilized trick photography in film fantasies that prefigured that in King Kong. Jungle films were launched in the United States in 1913 with Beasts in the Jungle, and the film’s popularity spawned similar pictures such as Tarzan of the Apes,.

In 1925, The Lost World made movie history with special effects by Willis O’Brien and a crew that later would work on King Kong. King Kong producer Ernest B. Schoedsack had earlier monkey experience directing Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness in 1927 (also with Merian C. Cooper) and Rango in 1931, both of which prominently featured monkeys in authentic jungle settings. Capitalizing on this trend, Congo Pictures released the hoax documentary Ingagi in 1930, advertising the film as “an authentic incontestable celluloid document showing the sacrifice of a living woman to mammoth gorillas.” Ingagi is now widely recognized as a racial exploitation film as it implicitly depicted black women having sex with gorillas, and baby offspring that looked more ape than human. The film was an immediate hit, and by some estimates it was one of the highest-grossing films of the 1930s at over $4 million. Although Cooper never listed Ingagi among his influences for King Kong, it has long been held that RKO green-lit Kong because of the bottom-line example of Ingagi and the formula that “gorillas plus sexy women in peril equals enormous profits”.

Merian C. Cooper’s fascination with gorillas began with his boyhood reading of Paul Du Chaillu’s Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa (1861) and was furthered in 1929 by studying a tribe of baboons in Africa while filming The Four Feathers. After reading W. Douglas Burden’s The Dragon Lizards of Komodo, he fashioned a scenario depicting African gorillas battling Komodo dragons intercut with artificial stand-ins for joint shots. He then narrowed the dramatis personae to one ferocious, lizard-battling gorilla (rather than a group) and included a lone woman on expedition to appease those critics who belabored him for neglecting romance in his films. A remote island would be the setting and the gorilla would be dealt a spectacular death in New York City.

Cooper took his concept to Paramount Studios in the first years of the Great Depression but executives shied away from a project that sent film crews on costly shoots to Africa and Komodo. In 1931, David O. Selznick brought Cooper to RKO as his executive assistant and promised him he could make his own films. Cooper began immediately developing The Most Dangerous Game, and hired Ernest B. Schoedsack to direct. A huge jungle stage set was built, with Robert Armstrong and Fay Wray as the stars. Once the film was underway, Cooper turned his attention to the studio’s big-budget-out-of-control fantasy, Creation, a project with stop motion animator Willis O’Brien about a group of travelers shipwrecked on an island of dinosaurs.

When Cooper screened O’Brien’s stop-motion Creation footage, he was unimpressed, but realized he could economically make his gorilla picture by scrapping the Komodo dragons and costly location shoots for O’Brien’s animated dinosaurs and the studio’s existing jungle set. It was at this time Cooper probably cast his gorilla as a giant named Kong, and planned to have him die at the Empire State Building. The RKO board was wary about the project, but gave its approval after Cooper organized a presentation with Wray, Armstrong, and Cabot, and O’Brien’s model dinosaurs. In his executive capacity, Cooper ordered the Creation production shelved, and put its crew to work on Kong.

Cooper assigned recently hired RKO screenwriter and best-selling British mystery/adventure writer Edgar Wallace the job of writing a screenplay and a novel based on his gorilla fantasy. Cooper understood the commercial appeal of Wallace’s name and planned to publicize the film as being “based on the novel by Edgar Wallace”. Wallace conferred with Cooper and O’Brien (who contributed, among other things, the “Ann’s dress” scene) and began work on January 1, 1932. He completed a rough draft called The Beast on January 5, 1932. Cooper thought the draft needed considerable work but Wallace died on February 10, 1932, just after beginning revisions. Despite not using any of the draft in the final production beyond the previously agreed upon plot outline, Cooper gave a screen credit to Wallace as he had promised it as a producer.

Cooper called in James Ashmore Creelman (who was working on the script of The Most Dangerous Game at the time) and the two men worked together on several drafts under the title The Eighth Wonder. Some details from Wallace’s rough draft were dropped, notably his boatload of escaped convicts. Wallace’s Danby Denham character, a big game hunter, became film director Carl Denham. His Shirley became Ann Darrow and her lover-convict John became Jack Driscoll. The ‘beauty and the beast’ angle was first developed at this time. Kong’s escape was switched from Madison Square Garden to Yankee Stadium and (finally) to a Broadway theater. Cute moments involving the gorilla in Wallace’s draft were cut because Cooper wanted Kong hard and tough in the belief that his fall would be all the more awesome and tragic.

Time constraints forced Creelman to temporarily drop The Eighth Wonder and devote his time to the Game script. RKO staff writer Horace McCoy was called in to work with Cooper, and it was he who introduced the island natives, a giant wall, and the sacrificial maidens into the plot. Leon Gordon also contributed to the screenplay in a minimal capacity; both he and McCoy went uncredited in the completed film. When Creelman returned to the script full-time, he hated McCoy’s ‘mythic elements’, believing the script already had too many over-the-top concepts, but Cooper insisted on keeping them in. RKO head Selznick and his executives wanted Kong introduced earlier in the film (believing the audience would grow bored waiting for his appearance), but Cooper persuaded them that a suspenseful build-up would make Kong’s entrance all the more exciting.

Cooper felt Creelman’s final draft was slow-paced, too full of flowery dialogue, weighted-down with long scenes of exposition, and written on a scale that would have been prohibitively expensive to film. Writer Ruth Rose (Schoedsack’s wife) was brought in to for rewrites and, although she had never written a screenplay, undertook the task with a complete understanding of Cooper’s style, streamlining the script and tightening the action. Rather than explaining how Kong would be transported to New York, for example, she simply cut from the island to the theater. She incorporated autobiographical elements into the script with Cooper mirrored in the Denham character, her husband Schoedsack in the tough but tender Driscoll character, and herself in struggling actress Ann Darrow. Rose also rewrote the dialogue and created the film’s opening sequence, showing Denham meeting Ann on the streets of New York. Cooper was delighted with Rose’s script, approving the newly re-titled Kong for production. Cooper and Schoedsack decided to co-direct scenes but their styles were different (Cooper was slow and meticulous, Schoedsack brisk) and they finally agreed to work separately, with Cooper overseeing O’Brien’s miniature work and directing the special effects sequences, and Schoedsack directing the dialogue scenes.

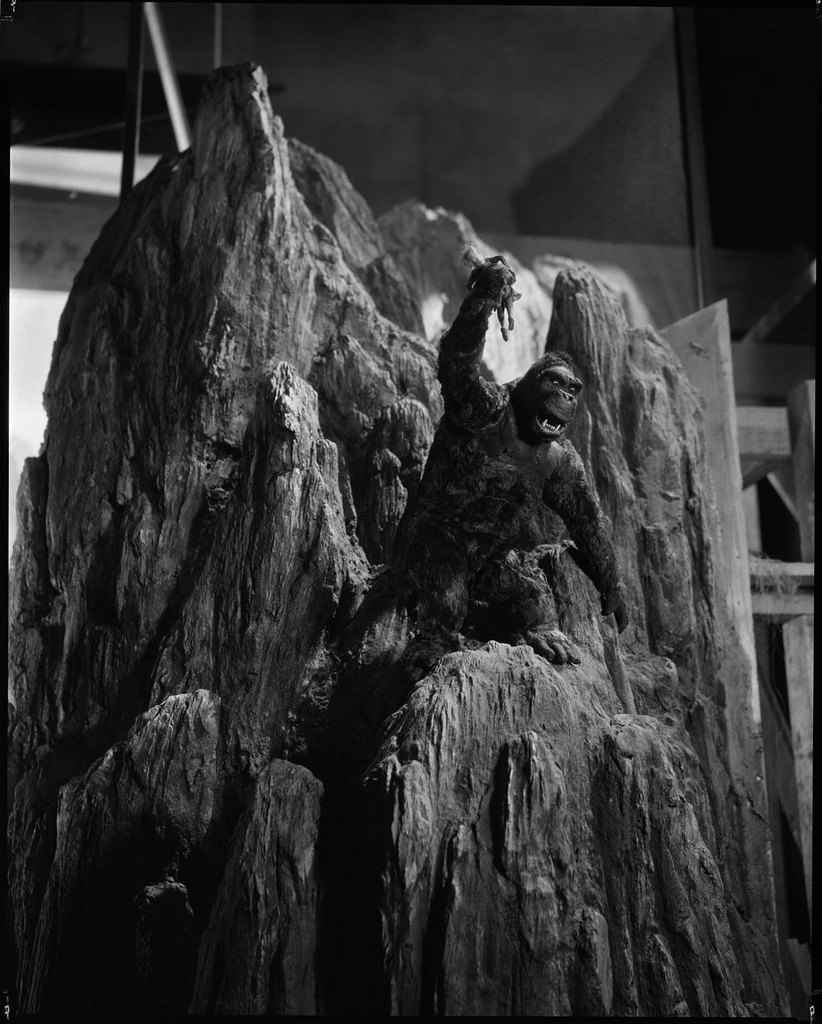

After the RKO board approved the production of a test reel, Marcel Delgado constructed Kong (or the “Giant Terror Gorilla” as he was then known) per designs and directions from Cooper and O’Brien on a one-inch-equals-one-foot scale to simulate a gorilla 18 feet tall. Four models were built: two jointed 18-inch aluminum, foam rubber, latex, and rabbit fur models (to be rotated during filming), one jointed 24-inch model of the same materials for the New York scenes, and a small model of lead and fur for the climactic plummeting-down-the-Empire-State-Building shot. At least two armatures have survived — one believed to be the original made for the test footage — and are owned by Peter Jackson and Bob Burns. In 2009, one sold for £121,000 ($200,000) at Christie’s in London.

Kong’s torso was streamlined to eliminate the comical appearance of the real world gorilla’s prominent belly and buttocks. His lips, eyebrows, and nose were fashioned of rubber, his eyes of glass, and his facial expressions controlled by thin, bendable wires threaded through holes drilled in his aluminum skull. During filming, Kong’s rubber skin dried out quickly under studio lights, making it necessary to replace it often and completely rebuild his facial features.

A huge bust of Kong’s head, neck, and upper chest was made of wood, cloth, rubber, and bearskin by Delgado, E. B. Gibson, and Fred Reefe. Inside the structure, metal levers, hinges, and an air compressor were operated by three men to control the mouth and facial expressions. Its fangs were 10 inches in length and its eyeballs 12 inches in diameter. The bust was moved from set to set on a flatcar. Its scale matched none of the models and, if fully realized, Kong would have stood thirty to forty feet tall.

Two versions of Kong’s right hand and arm were constructed of steel, sponge rubber, rubber, and bearskin. The first hand was non articulated, mounted on a crane, and operated by grips for the scene in which Kong grabs at Driscoll in the cave. The other hand and arm had articulated fingers, was mounted on a lever to elevate it, and was used in the several scenes in which Kong grasps Ann. A non articulated leg was created of materials similar to the hands, mounted on a crane, and used to stomp on Kong’s victims.

The dinosaurs were made by Delgado in the same fashion as Kong and based on Charles R. Knight’s murals in the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. All the armatures were manufactured in the RKO machine shop. Materials used were cotton, foam rubber, latex sheeting, and liquid latex. Football bladders were placed inside some models to simulate breathing. A scale of one-inch-equals-one-foot was employed and models ranged from 18 inches to 3 feet in length. Several of the models were originally built for Creation and sometimes two or three models were built of individual species. Prolonged exposure to studio lights wreaked havoc with the latex skin so John Cerasoli carved wooden duplicates of each model to be used as stand-ins for test shoots and lineups. He carved wooden models of Ann, Driscoll, and other human characters. Models of the Venture, railway cars, and war planes were built.

King Kong is well known for its groundbreaking use of special effects, such as stop-motion animation, matte painting, rear projection and miniatures, all of which were conceived decades before the digital age.

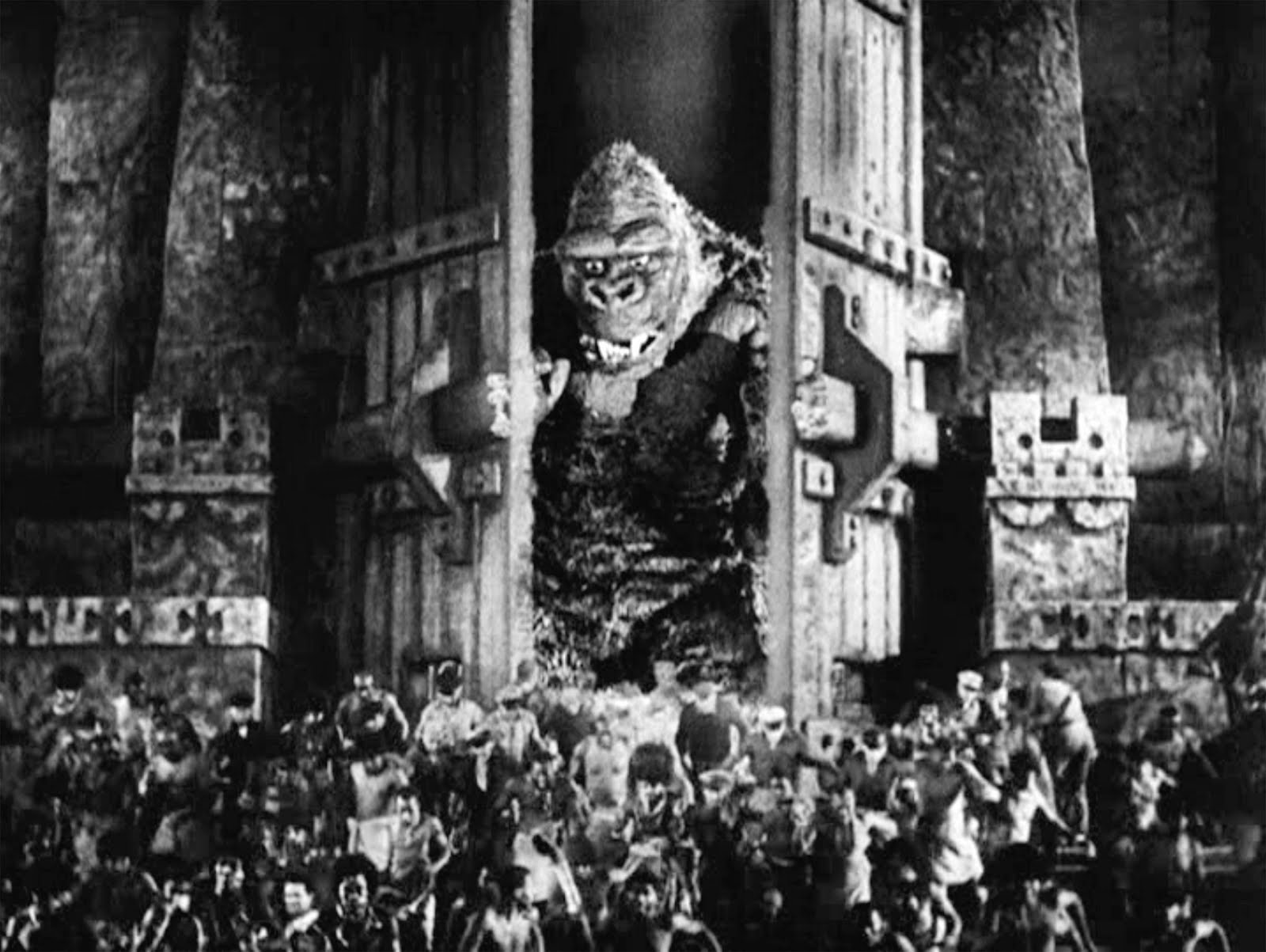

The numerous prehistoric creatures inhabiting Skull Island were brought to life through the use of stop-motion animation by Willis O’Brien and his assistant animator, Buzz Gibson. The stop-motion animation scenes were painstaking and difficult to achieve and complete after the special effects crew realized that they could not stop, because it would make the movements of the creatures seem inconsistent and the lighting would not have the same intensity over the many days it took to fully animate a finished sequence. A device called the surface gauge was used in order to keep track of the stop-motion animation performance. The iconic fight between Kong and the Tyrannosaurus took seven weeks to be completed. O’Brien’s protegé, Ray Harryhausen, who would work with him on several films and become one of the most prominent stop-motion animators in Hollywood, stated that O’Brien’s second wife noticed that there was so much of her husband in Kong.

The backdrop of Skull Island seen when the Venture crew first arrive was painted on glass by matte painters Henry Hillinck, Mario Larrinaga and Byron C. Crabbé. The scene was then composted with separate bird elements and rear projected behind the ship and the actors. The background of the scenes in the jungle (a miniature set) were also painted on several layers of glass to convey the illusion of deep and dense jungle foliage.

The most difficult task for the special effects artists to achieve was to make live-action footage interact with separately filmed stop-motion animation — to make the interaction between the humans and the creatures of the island seem believable. The most simple of these effects were accomplished by exposing part of the frame, then running the same piece of the film through the camera again by exposing the other part of the frame with a different image. The most complex shots, where the live-action actors interacted with the stop-motion animation, were achieved via two different techniques, the Dunning process and the Williams process, in order to produce the effect of a travelling matte.[40] The Dunning process, invented by cinematographer Carroll H. Dunning, employed the use of blue and yellow lighting, filtered and photographed into black-and-white film. Bi packing of the camera was used for these types of effects. With it, the special effects crew could combine two strips of different film at the same time, creating the final composite shot in the camera. It was used in the climactic scene where one of the Curtiss Helldiver planes attacking Kong crashes from the top of the Empire State Building, and in the scene where natives are running through the foreground, while Kong is fighting other natives at the wall.

On the other hand, the Williams process, invented by cinematographer Frank D. Williams, did not require a system of colored lights and could be used for wider shots. It was used in the scene where Kong is shaking the sailors off the log, as well as the scene where Kong pushes the gates open. The Williams process did not use bipacking, but rather an optical printer, the first such device that synchronized a projector with a camera, so that several strips of film could be combined into a single composited image. Through the use of the optical printer, the special effects crew could film the foreground, the stop-motion animation, the live-action footage, and the background, and combine all of those elements into one single shot. The optical printer would continue to be used for films until the late 1980s, when they were superseded by digital compositing.

Another technique that was used in combining live actors and stop-motion animation was rear-screen projection. The actor would have a translucent screen behind him where a projector would project footage onto the back of the translucent screen. The translucent screen was developed by Sidney Saunders and Fred Jackman, who received a Special Achievement Oscar. It was used in the famous scene where Kong and the Tyrannosaurus fight while Ann watches from the branches of a nearby tree. The stop-motion animation was filmed first. Fay Wray then spent a twenty-two hour period sitting in a fake tree acting out her observation of the battle, which was projected onto the translucent screen while the camera filmed her witnessing the projected stop-motion battle. She was sore for days after the shoot. The same process was also used for the scene where sailors from the Venture kill a Stegosaurus.

O’Brien and his special effects crew also devised a way to use rear-projection in miniature sets. A tiny screen was built into the miniature onto which live-action footage would then be projected. A fan pumped cool air to prevent the footage that was projected from melting or catching fire. This miniature rear projection was used in the scene where Kong is trying to grab Driscoll, who is hiding in a cave. The scene where Kong puts Ann in the top of a tree switched from a puppet in Kong’s hand to a projected footage of Ann sitting.

The scene where Kong fights the snake-like reptile in his lair was likely the most significant special effects achievement of the film, due to the way in which all of the elements in the sequence work together at the same time. The scene was accomplished through the use of a miniature set, stop-motion animation for Kong, background matte paintings, real water, foreground rocks with bubbling mud, smoke and two miniature rear screen projections of Driscoll and Ann.

Over the years, some media reports have alleged that in certain scenes Kong was played by an actor wearing a gorilla suit. However, film historians have generally agreed that all scenes involving Kong were achieved with animated models.

King Kong was filmed in several stages over an eight-month period. Some actors had so much time between their Kong periods that they were able to fully complete work on other films. Cabot completed Road House and Wray appeared in the horror films Dr. X and Mystery of the Wax Museum. She estimated she worked for ten weeks on Kong over its eight-month production.

In May and June 1932, Cooper directed the first live-action Kong scenes on the jungle set built for The Most Dangerous Game. Some of these scenes were incorporated into the test reel later exhibited for the RKO board. The script was still in revision when the jungle scenes were shot and much of the dialogue was improvised. The jungle set was scheduled to be struck after Game was completed, so Cooper filmed all of the other jungle scenes at this time. The last scene shot was that of Driscoll and Ann racing through the jungle to safety following their escape from Kong’s lair.

In July 1932, the native village was readied while Schoedsack and his crew filmed establishing shots in the harbor of New York City. Curtiss F8C-5/O2C-1 Helldiver war planes taking off and in flight were filmed at a U.S. Naval airfield on Long Island. Views of New York City were filmed from the Empire State Building for backgrounds in the final scenes and architectural plans for the mooring mast were secured from the building’s owners for a mock-up to be constructed on the Hollywood sound stage.

In August 1932, the island landing party scene and the gas bomb scene were filmed south of Los Angeles on a beach at San Pedro, California. All of the native village scenes were then filmed on the RKO-Pathé lot in Culver City with the native huts recycled from Bird of Paradise (1932). The great wall in the island scenes was a hand-me-down from DeMille’s The King of Kings (1927) and dressed up with massive gates, a gong, and primitive carvings. The scene of Ann being led through the gates to the sacrificial altar was filmed at night with hundreds of extras and 350 lights for illumination. A camera was mounted on a crane to follow Ann to the altar. The Culver City Fire Department was on hand due to concerns that the set might go up in flames from the many native torches used in the scene. The wall and gate were destroyed in 1939 for Gone With the Wind‘s burning of Atlanta sequence. Hundreds of extras were once again used for Kong’s rampage through the native village, and filming was completed with individual vignettes of mayhem and native panic.

Meanwhile, the scene depicting a New York woman being dropped to her apparent death from a hotel window was filmed on the sound stage using the articulated hand. At the same time, a scene depicting poker players surprised by Kong’s face peering through a window was filmed using the ‘big head’, although the scene was eventually dropped. When filming was completed, a break was scheduled to finish construction of the interior sets and to allow screenwriter Ruth Rose time to finish the script.

In September–October 1932, Schoedsack returned to the sound stage after completing the native village shoots in Culver City. The decks and cabins of the Venture were constructed and all the live-action shipboard scenes were then filmed. The New York scenes were filmed, including the scene of Ann being plucked from the streets by Denham, and the diner scene. Following completion of the interior scenes, Schoedsack returned to San Pedro and spent a day on a tramp steamer to film the scene of Driscoll punching Ann, and various atmospheric harbor scenes. The Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles was rented for one day to film the scenes where Kong is displayed in chains and the backstage theater scenes following his escape. Principal photography wrapped at the end of October 1932 with the filming of the climax wherein Driscoll rescues Ann at the top of the Empire State Building. Schoedsack’s work was completed and he headed to Syria to film outdoor scenes for Arabia, a project that was never completed.

In December 1932 and January 1933, the actors were called back to film a number of optical effects shots which were mostly rear-screen projections. Technical problems inherent in the process made filming difficult and time-consuming. Wray spent most of a twenty-two hour period sitting in a fake tree to witness the battle between Kong and a Tyrannosaurus. She was sore for days after. Many of the scenes featuring Wray in the articulated hand were filmed at this time. In December, Cooper re shot the scene of the female New Yorker falling to her death. Stunt doubles were filmed for the water scenes depicting Driscoll and Ann escaping from Kong. A portion of the jungle set was reconstructed to film Denham snagging his sleeve on a branch during the pursuit scene. Originally, Denham ducked behind a bush to escape danger, but this was later considered cowardly and the scene was re shot. The final scene was originally staged on the top of the Empire State Building, but Cooper was dissatisfied and re shot the scene with Kong lying dead in the street with the crowd gathered about him.

Murray Spivack provided the sound effects for the film. Kong’s roar was created by mixing the recorded roars of zoo lions and tigers, subsequently played backwards slowly. Spivak himself provided Kong’s “love grunts” by grunting into a megaphone and playing it at a slow speed. For the huge ape’s footsteps, Spivak stomped across a gravel-filled box with plungers wrapped in foam attached to his own feet, while the sounds of his chest beats were recorded by Spivak hitting his assistant (who had a microphone held to his back) on the chest with a drumstick. Spivak created the hisses and croaks of the dinosaurs with an air compressor for the former and his own vocals for the latter. The vocalizations of the Tyrannosaurus were additionally mixed in with puma screams. Bird squawks were used for the Pteranodon. Spivak also provided the numerous screams of the various sailors. Fay Wray herself provided all of her character’s screams in a single recording session.

For budget reasons, RKO decided not to have an original film score composed, instead instructing composer Max Steiner to simply reuse music from other films. Cooper thought the film deserved an original score and paid Steiner $50,000 to compose it. Steiner completed the score in six weeks and recorded it with a 46-piece orchestra. The studio later reimbursed Cooper. The score was unlike any that came before and marked a significant change in the history of film music. King Kong‘s score was the first feature-length musical score written for an American “talkie” film, the first major Hollywood film to have a thematic score rather than background music, the first to mark the use of a 46-piece orchestra, and the first to be recorded on three separate tracks (sound effects, dialogue, and music). Steiner used a number of new film scoring techniques, such as drawing upon opera conventions for his use of leitmotifs.

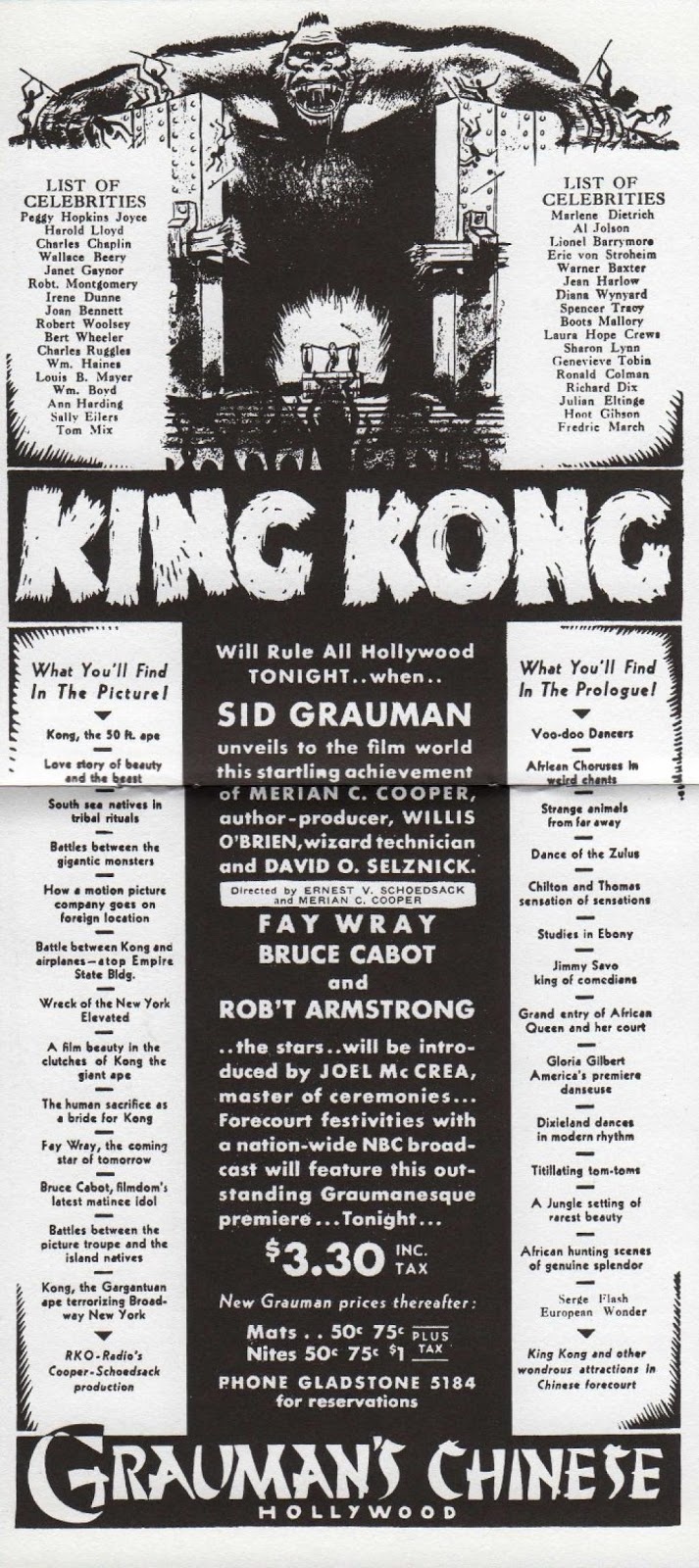

King Kong opened at the 6,200-seat Radio City Music Hall in New York City and the 3,700-seat RKO Roxy across the street on Thursday, March 2, 1933. The film was preceded by a stage show called Jungle Rhythms. Crowds lined up around the block on opening day, tickets were priced at $.35 to $.75, and, in its first four days, every one of its ten-shows-a-day were sold out — setting an all-time attendance record for an indoor event. Over the four-day period, the film grossed $89,931.

The film had its official world premiere on March 23, 1933 at Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood. The ‘big head bust’ was placed in the theater’s forecourt and a seventeen-act show preceded the film with The Dance of the Sacred Ape performed by a troupe of African American dancers the highpoint. Kong cast and crew attended and Wray thought her on-screen screams distracting and excessive. The film opened nationwide on April 10, 1933, and worldwide on Easter Day in London, England.

Variety thought the film was a powerful adventure. The New York Times gave readers an enthusiastic account of the plot and thought the film a fascinating adventure. John Mosher of The New Yorker called it “ridiculous”, but wrote that there were “many scenes in this picture that are certainly diverting”. The New York World-Telegram said it was “one of the very best of all the screen thrillers, done with all the cinema’s slickest camera tricks”. The Chicago Tribune called it “one of the most original, thrilling and mammoth novelties to emerge from a movie studio.”

On February 3, 2002, Roger Ebert included King Kong in his “Great Movies” list, writing that “In modern times the movie has aged, as critic James Berardinelli observes, and ‘advances in technology and acting have dated aspects of the production.’ Yes, but in the very artificiality of some of the special effects, there is a creepiness that isn’t there in today’s slick, flawless, computer-aided images…. Even allowing for its slow start, wooden acting and wall-to-wall screaming, there is something ageless and primeval about “King Kong” that still somehow works.”

The film was a box office success making about $2 million in worldwide rentals on its initial release, with an opening weekend estimated at $90,000. Receipts fell by up to 50% in the second week of the film’s release because of the national “bank holiday” called in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first days in office. During the film’s first run it made a profit of $650,000.

Prior to the 1952 re-release, the film is reported to have worldwide rentals of $2,847,000 including $1,070,000 from the United States and Canada and profits of $1,310,000.[3] After the 1952 re-release, Variety estimated the film had made an additional $1.6 million in the United States and Canada taking its total to $3.9 million in cumulative domestic (United States and Canada) rentals. Profits from the 1952 re-release were estimated by the studio at $2.5 million.

In the 19th and early 20th century, people of African descent were commonly visually represented as ape-like, a metaphor that fitted racist stereotypes, further bolstered by the emergence of scientific racism. Early blockbuster films frequently mirrored racial tensions. While King Kong is often compared to the story of Beauty and the Beast, many film scholars have argued that the film was a cautionary tale about interracial romance, in which the film’s “carrier of blackness is not a human being, but an ape”. Cooper and Schoedsack rejected any allegorical interpretations, insisting in interviews that the film’s story contained no hidden meanings.

Kong did not receive any Academy Awards nominations. Selznick wanted to nominate O’Brien and his crew for a special award in visual effects but the Academy declined. Such a category did not exist at the time and would not exist until 1938. Sidney Saunders and Fred Jackman received a special achievement award for the development of the translucent acetate/cellulose rear screen — the only Kong-related award.

The film has since received some significant honors. In 1975, Kong was named one of the 50 best American films by the American Film Institute, and, in 1991, the film was deemed “culturally, historically and aesthetically significant” by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry. In 1998, the AFI ranked the film #43 on its list of the 100 greatest movies of all time.

King Kong was re-released in 1938, 1942, 1946, 1952 and 1956; each time to great box office success. Stricter decency rules had been put into effect in Hollywood since its 1933 premiere and each time it was censored further, with several scenes being either trimmed or excised altogether.

These scenes were as follows:

- A Brontosaurus mauling crewmen in the water, chasing one up a tree and killing him;

- Kong undressing Ann Darrow and sniffing his fingers;

- Kong biting and stepping on natives when he attacks the village;

- Kong biting a reporter in New York;

- Kong mistaking a sleeping woman for Ann and dropping her to her death, after realizing his mistake.

- An additional scene portraying giant insects, spiders, a lizard and a tentacled creature devouring the crew members shaken off the log by Kong into the floor of the canyon below was deemed too gruesome by RKO even by pre-Code standards, and thus the scene was studio self-censored prior to original release. Though searched for, the footage is now considered “lost forever” with only a few stills and pre-production drawings.

After the 1956 re-release, the film was sold to television, first being broadcast March 5, 1956.

RKO had failed to preserve copies of film’s negative or release prints with the excised footage, and the cut scenes were considered lost for years. In 1969, a 16mm print, including the censored footage, was found in Philadelphia. The cut scenes were added to the film, restoring it to its original theatrical running time of 100 minutes. This version was re-released to art houses by Janus Films in 1970.

Over the next two decades, Universal Studios carried out further photochemical restoration on King Kong. This was based on a 1942 release print, with missing censor cuts taken from a 1937 print, which “contained heavy vertical scratches from projection.” An original release print located in the UK in the 1980s was found to contain the cut scenes in better quality.

After a 6-year worldwide search for the best surviving materials, a further, fully digital, restoration utilizing 4K resolution scanning was completed by Warner Bros. in 2005. This restoration also had a 4-minute overture added, bringing the overall running time to 104 minutes. King Kong was also, somewhat controversially, colorized in the late 1980s for television.

The 1933 King Kong film and character inspired imitations and installments. Son of Kong, a direct sequel to the 1933 film was released nine months after the first film’s release. In the early 1960s, RKO had licensed the King Kong character to Japanese studio Toho and produced two King Kong films, King Kong vs. Godzilla (a crossover with the Godzilla series) and King Kong Escapes, both directed by Ishirō Honda.

In 1976, Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis released his version of King Kong, a modern remake of the 1933 film, which was followed by a sequel in 1986 titled King Kong Lives. In 2005, Universal Pictures released another remake of King Kong, directed by Peter Jackson. Legendary Pictures and Warner Bros. released a Kong reboot film titled Kong: Skull Island in 2017 which was directed by Jordan Vogt-Roberts and is the second installment of a shared universe called the MonsterVerse, which started with Legendary’s reboot of Godzilla.

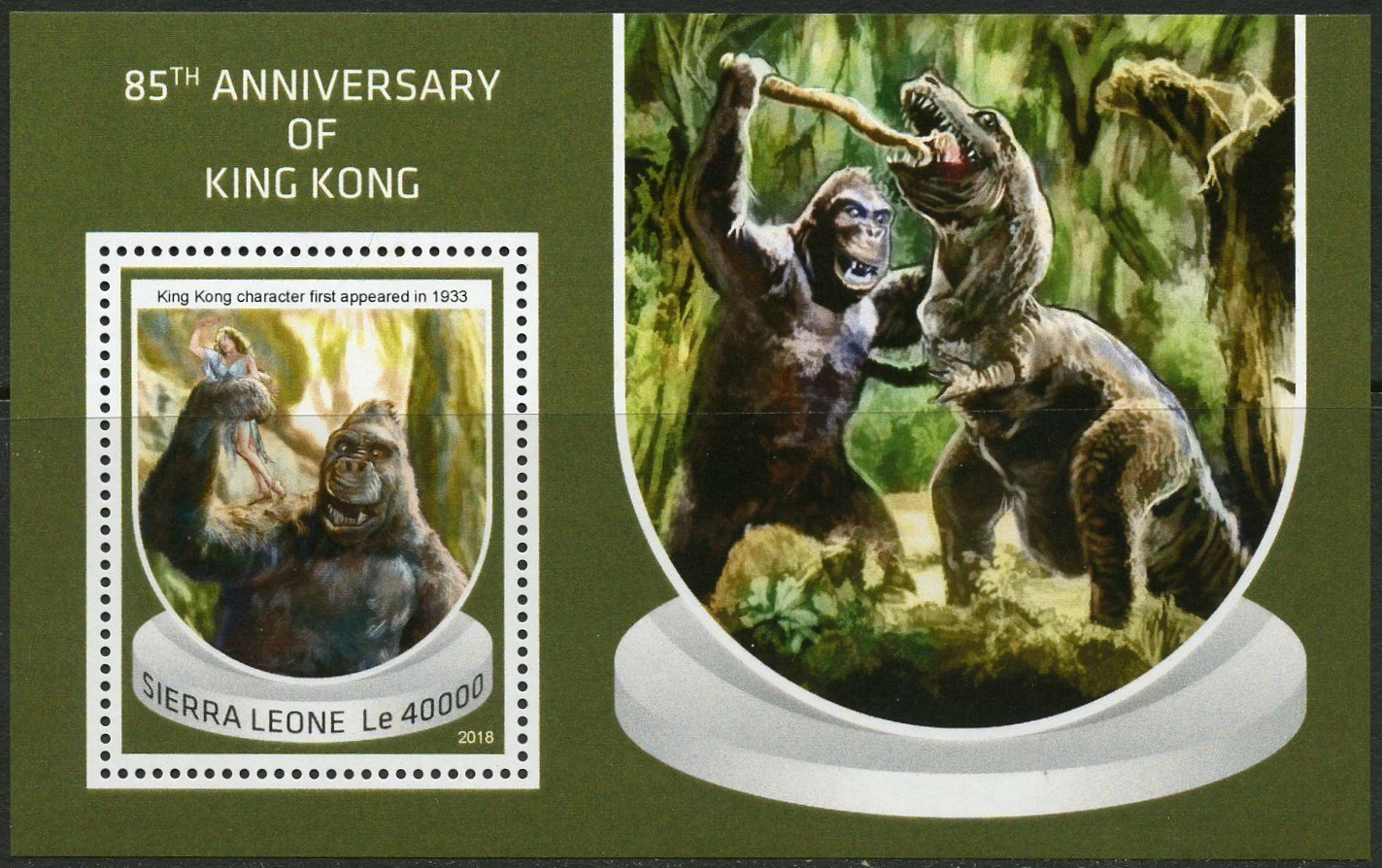

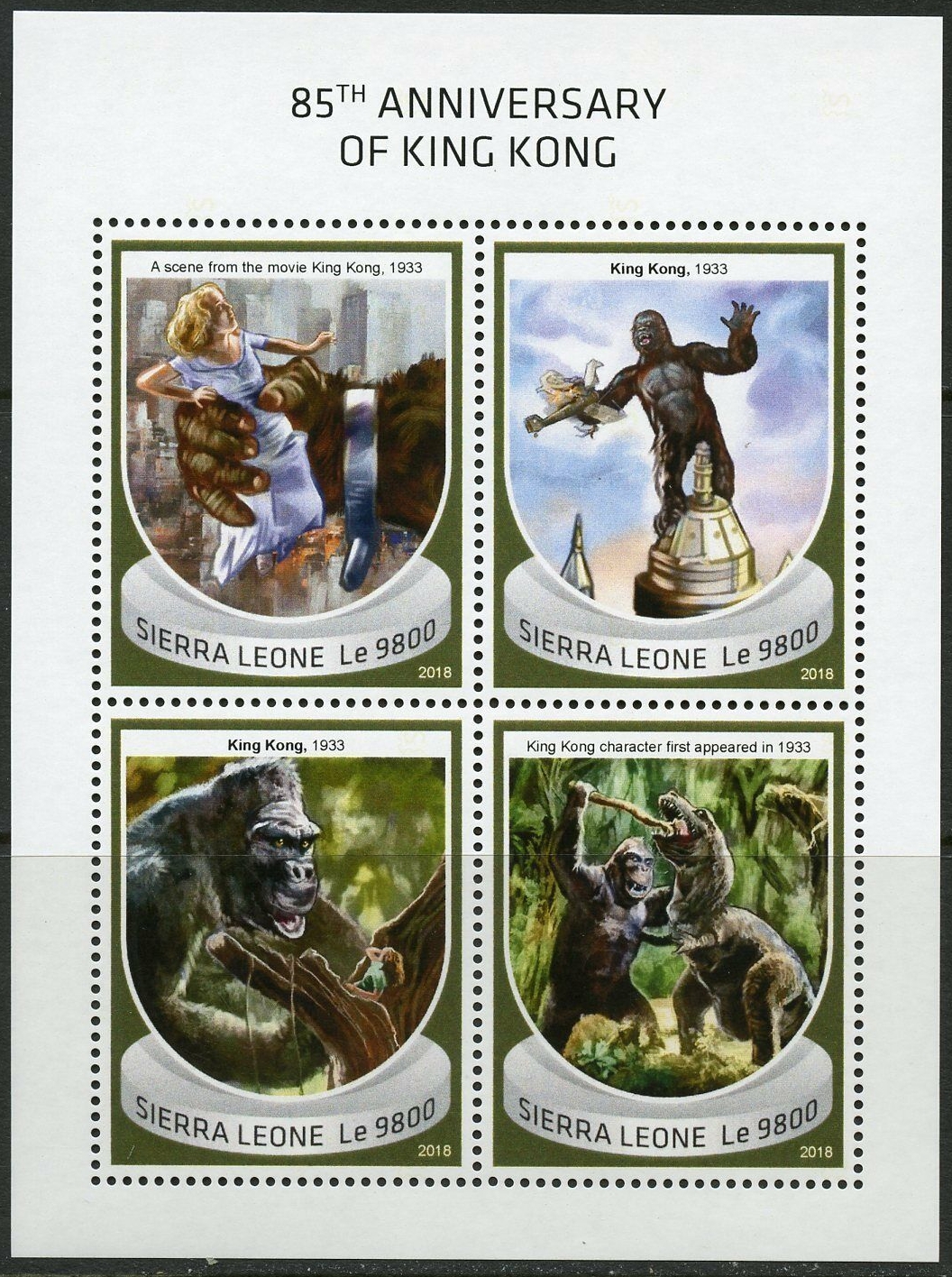

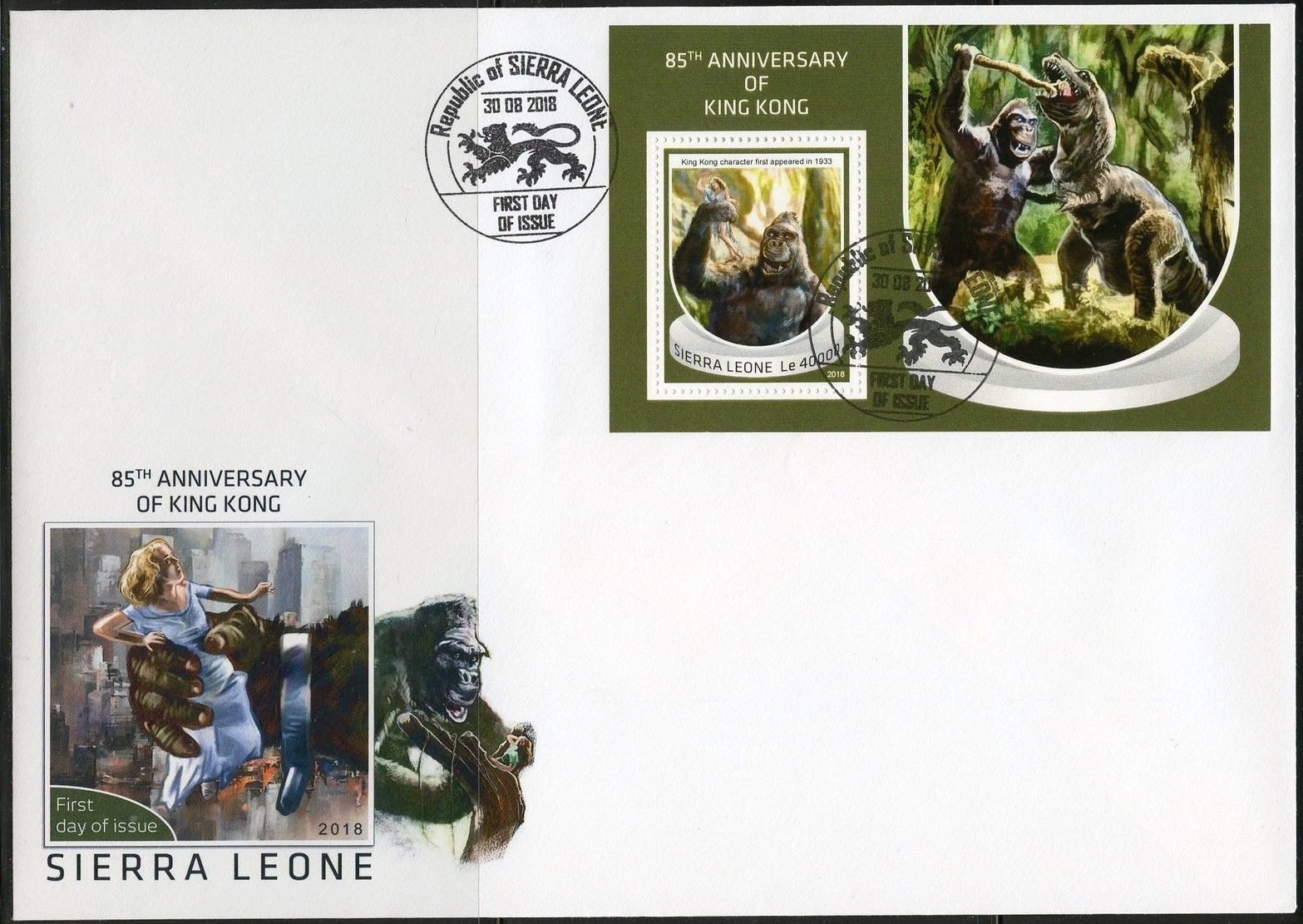

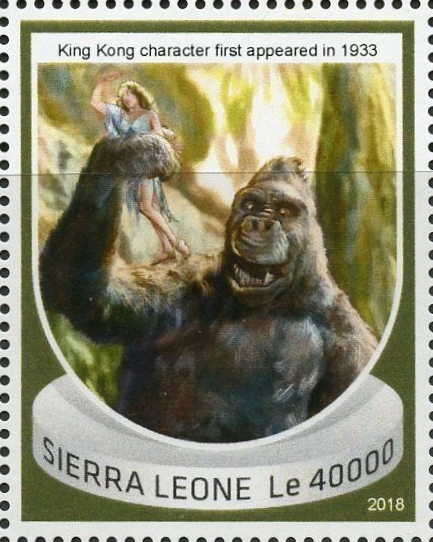

Several stamps have been issued commemorating the 1933 King Kong film. Fay Wray was included in a set of four designs in a mini-sheet released in 2006 (Scott #2153) and booklets (Scott #2153b). The Central African Republic marked the 80th anniversary of the movie with four stamps in a mini-sheet as well as a souvenir sheet of one released in 2013. Today’s featured stamp is a souvenir sheet issued by Sierra Leone on the occasion of the films’s 85th anniversary on August 25, 2018. A miniature sheet of four stamps accompanied this release.

One thought on “King Kong’s Film Debut”