Charles Dickens is right at the top of my list of favorite writers (I usually place him either even with or just below Samuel L. Clemons AKA Mark Twain). I took a look at the life of Dickens with a bit of a philatelic tribute on his birth anniversary in 2019, showcasing a few stamps and covers along with a brief biography. With 2020 marking the 150th anniversary of the author’s death, only a very few countries have yet announced stamps in commemoration including a very nice set from the Channel Island of Jersey released today.

Dickens’s approach to the novel was influenced by various things, including the picaresque novel tradition, melodrama, and the novel of sensibility. According to biographer Peter Ackroyd, other than these, perhaps the most important literary influence on him was derived from the fables of The Arabian Nights. Satire and irony are central to the picaresque novel. Comedy is also an aspect of the British picaresque novel tradition of Laurence Sterne, Henry Fielding, and Tobias Smollett. Fielding’s Tom Jones was a major influence on the 19th-century novel including Dickens, who read it in his youth, and named a son Henry Fielding Dickens in his honor. Melodrama is typically sensational and designed to appeal strongly to the emotions.

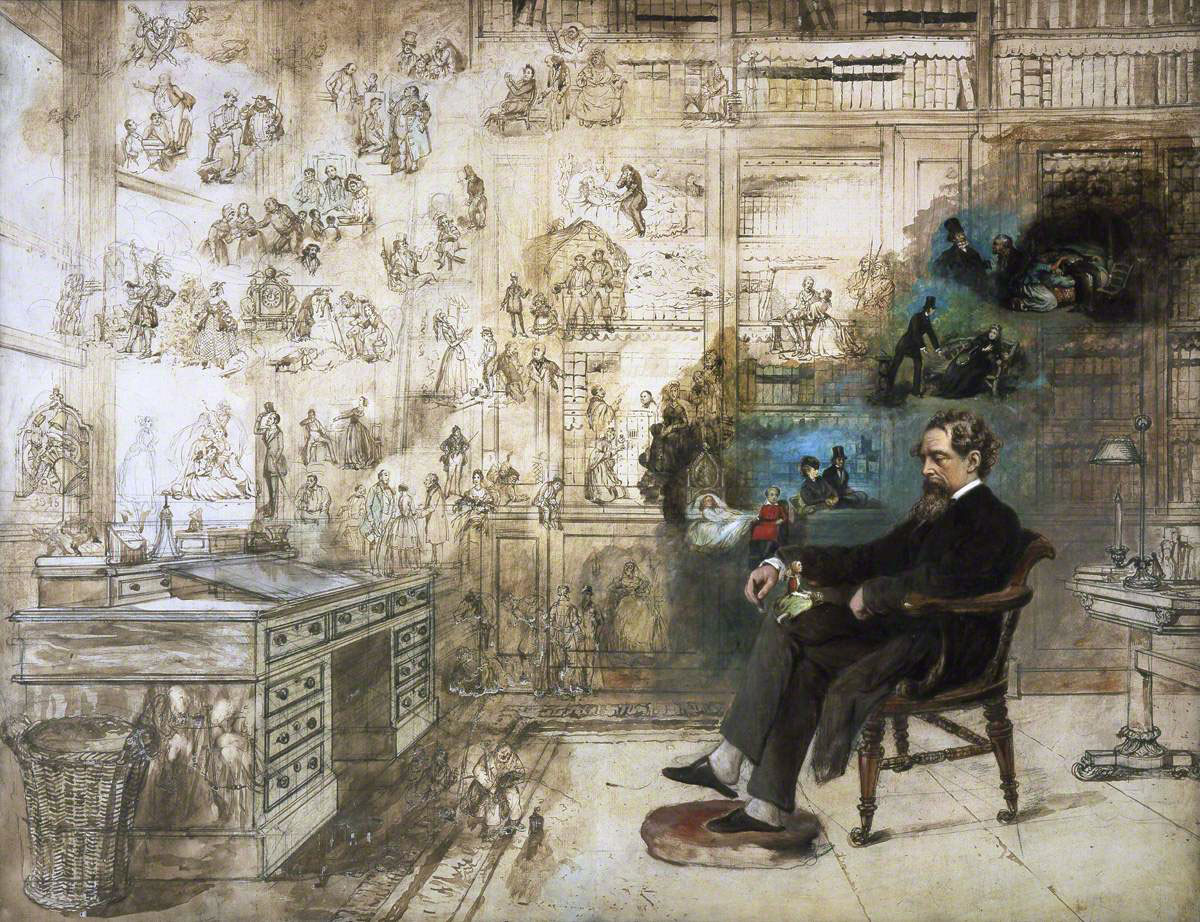

His writing style was marked by a profuse linguistic creativity. Satire, flourishing in his gift for caricature, was his forte. An early reviewer compared him to Hogarth for his keen practical sense of the ludicrous side of life, though his acclaimed mastery of varieties of class idiom may in fact mirror the conventions of contemporary popular theatre. Dickens worked intensively on developing arresting names for his characters that would reverberate with associations for his readers, and assist the development of motifs in the storyline, giving what one critic calls an “allegorical impetus” to the novels’ meanings. To cite one of numerous examples, the name Mr Murdstone in David Copperfield conjures up twin allusions to “murder” and stony coldness. His literary style is also a mixture of fantasy and realism. His satires of British aristocratic snobbery—he calls one character the “Noble Refrigerator”—are often popular. Comparing orphans to stocks and shares, people to tug boats, or dinner-party guests to furniture are just some of Dickens’s acclaimed flights of fancy.

The author worked closely with his illustrators, supplying them with a summary of the work at the outset and thus ensuring that his characters and settings were exactly how he envisioned them. He briefed the illustrator on plans for each month’s instalment so that work could begin before he wrote them. Marcus Stone, illustrator of Our Mutual Friend, recalled that the author was always “ready to describe down to the minutest details the personal characteristics, and … life-history of the creations of his fancy”.] Dickens employs Cockney English in many of his works, denoting working class Londoners. Cockney grammar appears in terms such as ain’t, and consonants in words are frequently omitted, as in ’ere (here), and wot (what). An example of this usage is in Oliver Twist. The Artful Dodger uses cockney slang which is juxtaposed with Oliver’s ‘proper’ English, when the Dodger repeats Oliver saying “seven” with “sivin”.

Dickens’s biographer Claire Tomalin regards him as the greatest creator of character in English fiction after Shakespeare. Dickensian characters are amongst the most memorable in English literature, especially so because of their typically whimsical names. The likes of Ebenezer Scrooge, Tiny Tim, Jacob Marley and Bob Cratchit (A Christmas Carol), Oliver Twist, The Artful Dodger, Fagin and Bill Sikes (Oliver Twist), Pip, Miss Havisham and Abel Magwitch (Great Expectations), Sydney Carton, Charles Darnay and Madame Defarge (A Tale of Two Cities), David Copperfield, Uriah Heep and Mr Micawber (David Copperfield), Daniel Quilp (The Old Curiosity Shop), Samuel Pickwick and Sam Weller (The Pickwick Papers), and Wackford Squeers (Nicholas Nickleby) are so well known as to be part and parcel of popular culture, and in some cases have passed into ordinary language: a scrooge, for example, is a miser – or someone who dislikes Christmas festivity.

His characters were often so memorable that they took on a life of their own outside his books. “Gamp” became a slang expression for an umbrella from the character Mrs. Gamp, and “Pickwickian”, “Pecksniffian”, and “Gradgrind” all entered dictionaries due to Dickens’s original portraits of such characters who were, respectively, quixotic, hypocritical, and vapidly factual. Many were drawn from real life: Mrs. Nickleby is based on his mother, though she didn’t recognize herself in the portrait, just as Mr. Micawber is constructed from aspects of his father’s ‘rhetorical exuberance’: Harold Skimpole in Bleak House is based on James Henry Leigh Hunt: his wife’s dwarfish chiropodist recognized herself in Miss Mowcher in David Copperfield. Perhaps Dickens’s impressions on his meeting with Hans Christian Andersen informed the delineation of Uriah Heep (a term synonymous with sycophant).

Virginia Woolf maintained that “we remodel our psychological geography when we read Dickens” as he produces “characters who exist not in detail, not accurately or exactly, but abundantly in a cluster of wild yet extraordinarily revealing remarks”. T. S. Eliot wrote that Dickens “excelled in character; in the creation of characters of greater intensity than human beings.” One “character” vividly drawn throughout his novels is London itself. Dickens described London as a magic lantern, inspiring the places and people in many of his novels. From the coaching inns on the outskirts of the city to the lower reaches of the Thames, all aspects of the capital – Dickens’ London – are described over the course of his body of work.

Authors frequently draw their portraits of characters from people they have known in real life. David Copperfield is regarded by many as a veiled autobiography of Dickens. The scenes of interminable court cases and legal arguments in Bleak House reflect Dickens’s experiences as a law clerk and court reporter, and in particular his direct experience of the law’s procedural delay during 1844 when he sued publishers in Chancery for breach of copyright. Dickens’s father was sent to prison for debt, and this became a common theme in many of his books, with the detailed depiction of life in the Marshalsea prison in Little Dorrit resulting from Dickens’s own experiences of the institution. Lucy Stroughill, a childhood sweetheart, may have affected several of Dickens’s portraits of girls such as Little Em’ly in David Copperfield and Lucie Manette in A Tale of Two Cities. Dickens may have drawn on his childhood experiences, but he was also ashamed of them and would not reveal that this was where he gathered his realistic accounts of squalor. Very few knew the details of his early life until six years after his death, when John Forster published a biography on which Dickens had collaborated.

Dickens’s novels were, among other things, works of social commentary. He was a fierce critic of the poverty and social stratification of Victorian society. In a New York address, he expressed his belief that “Virtue shows quite as well in rags and patches as she does in purple and fine linen”. Dickens’s second novel, Oliver Twist (1839), shocked readers with its images of poverty and crime: it challenged middle class polemics about criminals, making impossible any pretense to ignorance about what poverty entailed.

At a time when Britain was the major economic and political power of the world, Dickens highlighted the life of the forgotten poor and disadvantaged within society. Through his journalism he campaigned on specific issues—such as sanitation and the workhouse—but his fiction probably demonstrated its greatest prowess in changing public opinion in regard to class inequalities. He often depicted the exploitation and oppression of the poor and condemned the public officials and institutions that not only allowed such abuses to exist, but flourished as a result. His most strident indictment of this condition is in Hard Times (1854), Dickens’s only novel-length treatment of the industrial working class. In this work, he uses vitriol and satire to illustrate how this marginalized social stratum was termed “Hands” by the factory owners; that is, not really “people” but rather only appendages of the machines they operated. His writings inspired others, in particular journalists and political figures, to address such problems of class oppression. For example, the prison scenes in The Pickwick Papers are claimed to have been influential in having the Fleet Prison shut down.

Karl Marx asserted that Dickens “issued to the world more political and social truths than have been uttered by all the professional politicians, publicists and moralists put together”. George Bernard Shaw even remarked that Great Expectations was more seditious than Marx’s Das Kapital. The exceptional popularity of Dickens’s novels, even those with socially oppositional themes (Bleak House, 1853; Little Dorrit, 1857; Our Mutual Friend, 1865), not only underscored his ability to create compelling storylines and unforgettable characters, but also ensured that the Victorian public confronted issues of social justice that had commonly been ignored. It has been argued that his technique of flooding his narratives with an ‘unruly superfluity of material’ that, in the gradual dénouement, yields up an unsuspected order, influenced the organization of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species.

Dickens was the most popular novelist of his time, and remains one of the best-known and most-read of English authors. His works have never gone out of print, and have been adapted continually for the screen since the invention of cinema, with at least 200 motion pictures and TV adaptations based on Dickens’s works documented. Many of his works were adapted for the stage during his own lifetime, and as early as 1913, a silent film of The Pickwick Papers was made.

Dickens created some of the world’s best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest British novelist of the Victorian era. His literary reputation, however began to decline with the publication of Bleak House in 1852–53. Philip Collins calls Bleak House ‘a crucial item in the history of Dickens’s reputation. Reviewers and literary figures during the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s, saw a “drear decline” in Dickens, from a writer of “bright sunny comedy … to dark and serious social” commentary. The Spectator called Bleak House “a heavy book to read through at once … dull and wearisome as a serial”; Richard Simpson, in The Rambler, characterized Hard Times as ‘this dreary framework’; Fraser’s Magazine thought Little Dorrit ‘decidedly the worst of his novels’. All the same, despite these “increasing reservations amongst reviewers and the chattering classes, ‘the public never deserted its favourite’”. Dickens’s popular reputation remained unchanged, sales continued to rise, and Household Words and later All the Year Round were highly successful.

Later in his career, Dickens’ fame and the demand for his public readings were unparalleled. In 1868 The Times wrote, “Amid all the variety of ‘readings’, those of Mr Charles Dickens stand alone.” A Dickens biographer, Edgar Johnson, wrote in the 1950s: “It was [always] more than a reading; it was an extraordinary exhibition of acting that seized upon its auditors with a mesmeric possession.” Comparing his reception at public readings to those of a contemporary pop star, The Guardian states, “People sometimes fainted at his shows. His performances even saw the rise of that modern phenomenon, the “speculator” or ticket tout (scalpers) – the ones in New York City escaped detection by borrowing respectable-looking hats from the waiters in nearby restaurants.”

Among fellow writers, there was a range of opinions on Dickens. Poet laureate, William Wordsworth (1770–1850), thought him a “very talkative, vulgar young person”, adding he had not read a line of his work, while novelist George Meredith (1828–1909), found Dickens “intellectually lacking”. In 1888 Leslie Stephen commented in the Dictionary of National Biography that “if literary fame could be safely measured by popularity with the half-educated, Dickens must claim the highest position among English novelists”. Anthony Trollope’s Autobiography famously declared Thackeray, not Dickens, to be the greatest novelist of the age. However, both Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoyevsky were admirers. Dostoyevsky commented: “We understand Dickens in Russia, I am convinced, almost as well as the English, perhaps even with all the nuances. It may well be that we love him no less than his compatriots do. And yet how original is Dickens, and how very English!” Tolstoy referred to David Copperfield as his favorite book, and he later adopted the novel as “a model for his own autobiographical reflections.”

French writer Jules Verne called Dickens his favorite writer, writing his novels “stand alone, dwarfing all others by their amazing power and felicity of expression.” Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh was inspired by Dickens’s novels in several of his paintings like Vincent’s Chair and in an 1889 letter to his sister stated that reading Dickens, especially A Christmas Carol, was one of the things that was keeping him from committing suicide. Oscar Wilde generally disparaged his depiction of character, while admiring his gift for caricature. Henry James denied him a premier position, calling him “the greatest of superficial novelists”: Dickens failed to endow his characters with psychological depth and the novels, “loose baggy monsters”, betrayed a “cavalier organisation”. Joseph Conrad described his own childhood in bleak Dickensian terms, and noted he had “an intense and unreasoning affection” for Bleak House, dating back to his boyhood. The novel influenced his own gloomy portrait of London in The Secret Agent (1907). Virginia Woolf had a love-hate relationship with his works, finding his novels “mesmerizing” while reproving him for his sentimentalism and a commonplace style.

Dickens was a favorite author of Roald Dahl’s; the best-selling children’s author would include three of Dickens’ novels among those read by the title character in his 1988 novel Matilda. An avid reader of Dickens, in 2005, Paul McCartney named Nicholas Nickleby his favorite novel. On Dickens he states, “I like the world that he takes me to. I like his words; I like the language”, adding, “A lot of my stuff – it’s kind of Dickensian.” Screenwriter Jonathan Nolan’s screenplay for The Dark Knight Rises (2012) was inspired by A Tale of Two Cities, with Nolan calling the depiction of Paris in the novel “one of the most harrowing portraits of a relatable, recognisable civilisation that completely folded to pieces”. On 7 February 2012, the 200th anniversary of Dickens’s birth, Philip Womack wrote in The Telegraph: “Today there is no escaping Charles Dickens. Not that there has ever been much chance of that before. He has a deep, peculiar hold upon us”.

Between 1868 and 1869, Dickens gave a series of “farewell readings” in England, Scotland, and Ireland, beginning on 6 October. He managed, of a contracted 100 readings, to deliver 75 in the provinces, with a further 12 in London. As he pressed on he was affected by giddiness and fits of paralysis. He suffered a stroke on 18 April 1869 in Chester. He collapsed on 22 April 1869, at Preston in Lancashire, and on doctor’s advice, the tour was cancelled. After further provincial readings were cancelled, he began work on his final novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. It was fashionable in the 1860s to ‘do the slums’ and, in company, Dickens visited opium dens in Shadwell, where he witnessed an elderly addict known as “Laskar Sal”, who formed the model for the “Opium Sal” subsequently featured in his final novel.

After Dickens had regained sufficient strength, he arranged, with medical approval, for a final series of readings to partially make up to his sponsors what they had lost due to his illness. There were 12 performances, running between 11 January and 15 March 1870, the last at 8:00 pm at St. James’s Hall in London. Although in grave health by this time, he read A Christmas Carol and The Trial from Pickwick. On 2 May, he made his last public appearance at a Royal Academy Banquet in the presence of the Prince and Princess of Wales, paying a special tribute on the death of his friend, the illustrator Daniel Maclise.

On 8 June 1870, Dickens suffered another stroke at his home after a full day’s work on Edwin Drood. He never regained consciousness, and the next day, he died at Gads Hill Place. Biographer Claire Tomalin has suggested Dickens was actually in Peckham when he suffered the stroke, and his mistress Ellen Ternan and her maids had him taken back to Gad’s Hill so the public would not know the truth about their relationship. Contrary to his wish to be buried at Rochester Cathedral “in an inexpensive, unostentatious, and strictly private manner”, he was laid to rest in the Poets’ Corner of Westminster Abbey. A printed epitaph circulated at the time of the funeral reads:

To the Memory of Charles Dickens (England’s most popular author) who died at his residence, Higham, near Rochester, Kent, 9 June 1870, aged 58 years. He was a sympathiser with the poor, the suffering, and the oppressed; and by his death, one of England’s greatest writers is lost to the world.

In his will, drafted more than a year before his death, Dickens left the care of his £80,000 estate to his longtime colleague John Forster and his “best and truest friend” Georgina Hogarth who, along with Dickens’s two sons, also received a tax-free sum of £8,000 (about £800,000 in present terms). Although Dickens and his wife had been separated for several years at the time of his death, he provided her with an annual income of £600 and made her similar allowances in his will. He also bequeathed £19 19s to each servant in his employment at the time of his death.

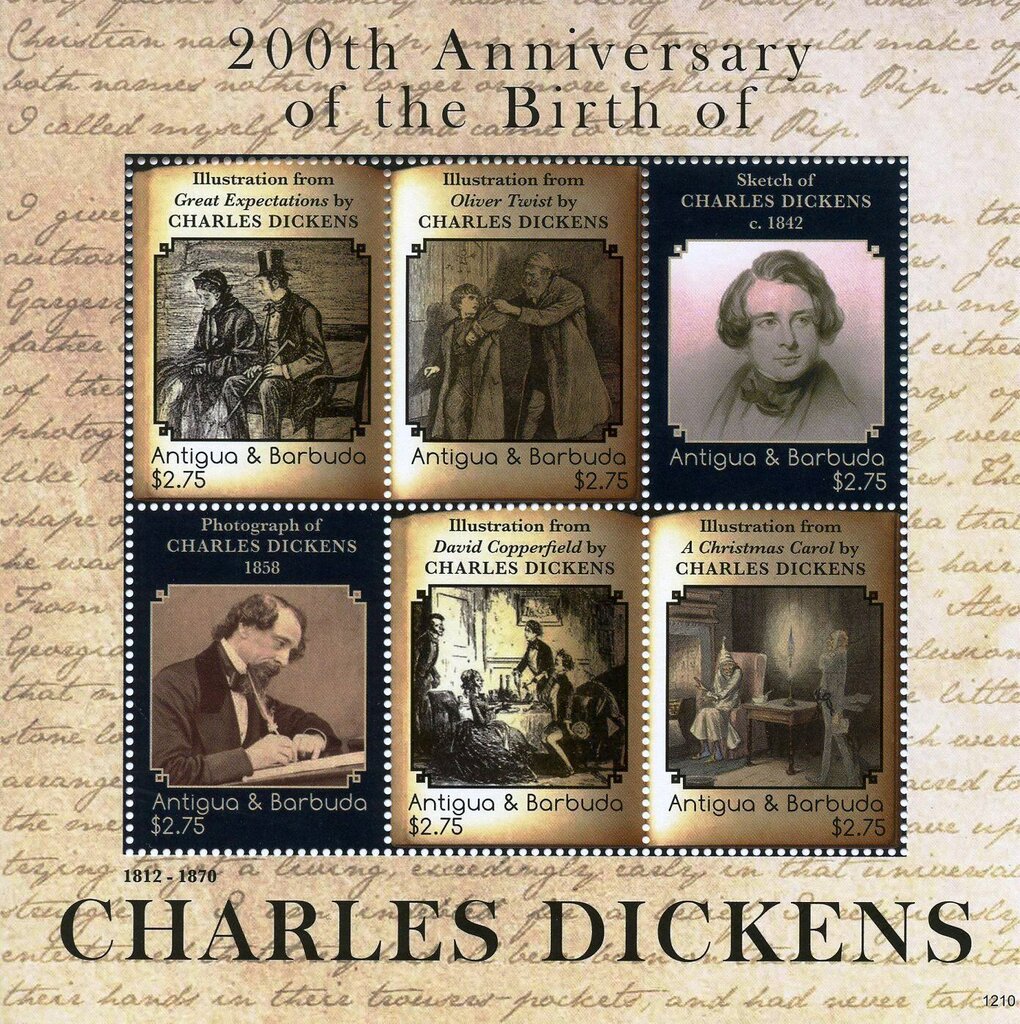

Dickens and his characters have appeared on a number of postage stamps. Although there was a label printed in 1912 to commemorate the centenary of his birth (and meant to benefit Dickens’s descendants), I believe the earliest postage stamp was released by the Soviet Union on 29 April 1962 (Scott #2588). The next was issued just over eight years later, by Saint Kitts-Nevis-Antigua on 1 May 1970 (Scott #226) which kicked-off a plethora of British Commonwealth issues commemorating the 100th anniversary of the author’s death.

Today’s featured stamp was issued by Saint Lucia a day before Dickens’s death anniversary, 8 June 1970. Scott #278 is the low value in a set of four issued by the Caribbean island, the stamps differing only in denomination (1, 25, 35, and 50 East Caribbean cents) and color. They were printed using offset lithography and are perforated 14.

Entities that have issued stamps portraying Charles Dickens or characters from his works include: Soviet Union (1962); Botswana, Cameroon, Dubai, Fujairah, St Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla, St Lucia, and Turks and Caicos Islands (1970); Great Britain (1970, 1993, 2011 and 2012); St. Helena (1970 and 2006); St Vincent and the Grenadines (1987); Nevis (2007); Guinea (2008); Sierra Leone (2010); Antigua & Barbuda, Ascension Island, Gibraltar, Mozambique, and Pitcairn Islands (2012), Austria (2013), Mozambique (2014), Alderney (2018); Bosnia Herzegovina (BH Pošta) and Jersey (2020). The Philatelic Database includes a nice write-up on this particular theme.

Today’s issues come from Bosnia and Herzegovina (the BH Pošta administration in a nation that includes three separate postal services) and Jersey in the British Channel Islands. The latter features eight stamps portraying characters from Dickens’s novels along with a matching miniature sheet and a set of postcards. A full write-up appears on my sister site, Philatelic Pursuits.

I can’t say I’m a huge fans of Dickens but boy, some country made beautiful stamps about him!

LikeLike