On August 17, 1807, a 150-foot (46 meter) long boat developed by American engineer and inventor Robert Fulton sailed from New York City on a voyage up the Hudson River — at that time often called the North River —to Albany, 150 miles away, That boat was the North River Steamboat but now remembered as the Clermont and is widely regarded as he world’s first vessel to demonstrate the viability of using steam propulsion for commercial water transportation. Previously, in 1800, Fulton had been commissioned by Napoleon Bonaparte to attempt to design the Nautilus, the first practical submarine in history. He is also credited with inventing some of the world’s earliest naval torpedoes for use by the British Royal Navy.

Fulton had become interested in steam engines and the idea of steamboats in 1777 when he was around age 12 and visited state delegate William Henry of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, who himself had earlier learned about inventor James Watt and his Watt steam engine on a visit to England.

Robert Fulton was born on a farm in Little Britain, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, on November 14, 1765. He had three sisters — Isabella, Elizabeth, and Mary — and a younger brother, Abraham. He married Harriet Livingston and had four children, Julia, Mary, Cornelia, and Robert. His father, Robert, had been a close friend to the father of painter Benjamin West. Fulton later met West in England and they became friends.

Fulton stayed in Philadelphia for six years, where he painted portraits and landscapes, drew houses and machinery, and was able to send money home to help support his mother. In 1785, he bought a farm at Hopewell Township in Washington County for £80 Sterling and moved his mother and family into it. While in Philadelphia, he met Benjamin Franklin, then known not only for his political and writing abilities but his scientific and inventing knowledge. At age 23, Fulton decided to visit Europe.

Fulton came to England in 1786, carrying several letters of introduction to Americans abroad from the individuals he had met in Philadelphia. He had already corresponded with Benjamin West, and West took Fulton into his home, where Fulton lived for several years. Fulton gained many commissions painting portraits and landscapes, which allowed him to support himself, but he continually experimented with mechanical inventions.

He became caught up in the enthusiasm of the “Canal Mania” and in 1793 began developing his ideas for tub-boat canals with inclined planes instead of locks. Fulton obtained a patent for this idea in 1794 and also began working on ideas for the steam power of boats. He published a pamphlet about canals and patented a dredging machine and several other inventions. In 1794, he moved to Manchester to gain practical knowledge of English canal engineering. Whilst there he became friendly with Robert Owen, the cotton manufacturer and early socialist. Owen agreed to finance the development and promotion of Fulton’s designs for inclined planes and earth-digging machines and was instrumental in introducing him to a canal company where he was awarded a sub-contract. However, this practical experience was not a success and he gave up the contract after a short time.

In 1797, Fulton went to Paris where his fame as an inventor was well known. In Paris, then along with London, the scientific centers of the 18th century world, he studied languages — French and German — along with mathematics and chemistry. He began to design torpedoes and submarines. In Paris, Fulton met James Rumsey, who sat for a portrait in West’s studio, where Fulton was an apprentice. Rumsey was an inventor from Virginia who ran his own first steamboat up the Potomac River near Shepherdstown, then in Virginia in 1786.

As early as 1793, Fulton proposed plans for steam-powered vessels to both the United States and British governments, and in England he met the Duke of Bridgewater Francis Egerton, whose canal, the first to be constructed in Britain, was being used for trials of a steam tug. Fulton became very enthusiastic about the canals and in 1796 wrote a treatise on canal construction, suggesting improvements to locks and other features. Working for the Duke of Bridgewater between 1796 and 1799, he had a boat constructed in the Duke’s timber yard, under the supervision of Benjamin Powell. After installation of the machinery supplied by the engineers Bateman and Sherratt of Salford, the boat was duly christened Bonaparte in honor of Fulton having served under Napoleon. After expensive trials, because of the configuration of the design, it was feared the paddles may damage the clay lining of the canal and the experiment was eventually abandoned. In 1801 the Duke, impressed by the Charlotte Dundas constructed by William Symington, decided to order eight of such vessels for his canal, but when he died in 1803, the order was cancelled. Symington had successfully tried steamboats in 1788, and it seems probable that Fulton was aware of these developments.

The first successful trial run of a steamboat had been made several years earlier by inventor John Fitch, on the Delaware River on August 22, 1787, in the presence of delegates from the Constitutional Convention, then observing and taking a break from its summer-long sessions at Independence Hall. It was propelled by a bank of oars on either side of the boat. The following year, Fitch launched a 60-foot (18 m) boat powered by a steam engine driving several stern mounted oars. These oars paddled in a manner similar to the motion of a swimming duck’s feet. With this boat he carried up to thirty passengers on numerous round-trip voyages on the upper Delaware River between Philadelphia and Burlington, New Jersey.

Fitch was granted a patent on August 26, 1791, after a battle with Rumsey, who had created a similar invention. Unfortunately, the newly created Patent Commission did not award the broad monopoly patent that Fitch had asked for, but a patent of the modern kind, for the new design of Fitch’s steamboat. It also awarded patents to Rumsey and John Stevens for their steamboat designs, and the loss of a monopoly caused many of Fitch’s investors to leave his company. While his boats were mechanically successful, Fitch failed to pay sufficient attention to construction and operating costs and was unable to justify the economic benefits of steam navigation. It was Fulton who would turn Fitch’s idea into a more profitable proposition decades later.

In 1797, Fulton went to France, where Claude de Jouffroy had made a working paddle steamer in 1783, and commenced experimenting with submarine torpedoes and torpedo boats. Fulton is the exhibitor of the first panorama painting to be shown in Paris, “Vue de Paris depuis les Tuilerie” painted by Pierre Prévost, Jean Mouchet, and Denis Fontaine and completed by 1800. The street where his panorama was shown is still called Rue des Panoramas (Panorama Street) today.

Fulton designed the first working submarine, the Nautilus between 1793 and 1797, while living in France. When tested his submarine went underwater for 17 minutes in 25 feet of water. He asked the government to subsidize its construction but he was turned down twice. Eventually he approached the Minister of Marine himself and in 1800 was granted permission to build. The shipyard Perrier in Rouen built it and it sailed first in July 1800 on the Seine River in the same city.

In France, Fulton also met Robert R. Livingston, who was appointed U.S. Ambassador to France in 1801, who was also of a scientifically curious mind, and they decided to build a steamboat together and try running it on the Seine. Fulton experimented with the water resistance of various hull shapes, made drawings and models, and had a steamboat constructed. At the first trial the boat ran perfectly, but the hull was later rebuilt and strengthened, and on August 9, 1803, this boat steamed up the River Seine, but sank. The boat was 66 feet (20.1 m) long, 8 feet (2.4 m) beam, and made between 3 and 4 miles per hour (4.8 and 6.4 km/h) against the current.

In 1804, Fulton switched allegiance and moved to England, where he was commissioned by the Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger to build a range of weapons for use by the Royal Navy during Napoleon’s invasion scares. Among his inventions were the world’s first modern naval “torpedoes” (modern “mines”), which were tested, along with several other of his inventions, during the 1804 Raid on Boulogne, but met with limited success. Although he continued to develop his inventions with the British until 1806, the decisive naval victory by Admiral Horatio Nelson at the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar greatly reduced the risk of French invasion, and Fulton found himself being increasingly ignored.

In 1806, Fulton returned to America and married Harriet Livingston, the niece of Robert Livingston and daughter of Walter Livingston. They had four children — Robert, Julia, Mary and Cornelia.

Livingston had obtained from the New York legislature the exclusive right to steam navigation on the Hudson River. With the success of the small paddle steamer they had tested on the Seine, Livingston contracted with Fulton to take advantage of his Hudson River monopoly and build a larger version for commercial service.

Their larger steamer was built at the Charles Browne shipyard in New York and was fitted with Fulton’s innovative steam engine design, manufactured for Livingston and Fulton by Boulton and Watt in Birmingham, England. Before she was later widened, the vessel’s original dimensions were 150 feet (46 m) long × 12 feet (3.7 m) wide × 7 feet (2.1 m) deep; she drew a little more than 2 feet (60 cm) of water when launched. The steamer was equipped with two paddle wheels, one each to a side, each paddle wheel assembly was equipped with two sets of eight spokes. She also carried two masts with spars, rigging, and sails, likely a foremast with square sail and a mizzen mast with fore-and-aft sail (spanker), with the steam engine placed amidships, directly behind the paddle wheel’s drive gear machinery.

Robert Fulton described the vessel by writing:

“My first steamboat on the Hudson’s River was 150 feet long, 13 feet wide, drawing 2 ft. of water, bow and stern 60 degrees: she displaced 36.40 [sic] cubic feet, equal 100 tons of water; her bow presented 26 ft. to the water, plus and minus the resistance of 1 ft. running 4 miles an hour.”

In the Nautical Gazette the editor, Mr. Samuel Ward Stanton, gave the following additional details:

“The bottom of the boat was formed of yellow pine plank 1.5 in. thick, tongued and grooved, and set together with white lead. This bottom or platform was laid in a transverse platform and molded out with batten and nails. The shape of the bottom being thus formed, the floors of oak and spruce were placed across the bottom; the spruce floors being 4×8 inches and 2 feet apart. The oak floors were reserved for the ends, and were both sided and molded 8 inches. Her top timbers (which were of spruce and extended from a log that formed the bridge to the deck) were sided 6 inches and molded at heel, and both sided and molded 4 inches at the head. She had no guards when first built and was steered by a tiller. Her draft of water was 28 inches.”

The boat had three cabins with 54 berths, kitchen, larder, pantry, bar, and steward’s room. The paddle wheels were 4 feet (1.2 m) wide and 15 feet (4.6 m) in diameter.

The steamer’s inaugural run was helmed by Captain Andrew Brink, and left New York City on August 17, 1807, with a complement of invited guests aboard. Notable passengers on the maiden voyage included infant Alexandria Jones, the daughter of a prominent lawyer from Bethlemem, PA. who later would serve on a steamboat hospital as a nurse for the Union in the Civil War. In the early afternoon of August 18, as the steamboat docked at Livingston’s estate, Clermont Manor, Livingston came down from his mansion to give a short speech. He tried to speak over the ominous noise of the steamboat to announce the betrothal of Harriet Livingston to Fulton, but to no avail. The steamboat managed to steal the spotlight by billowing thick smoke and a loud monstrous sound. Livingston’s speech was engulfed by the billowing beast that stood behind him. The steamboat arrived upstream at the state capital of Albany, New York, after 32 hours of travel time. They were greeted with onlookers galore and a cheer from the growing crowds. The return trip was uneventful, with fewer onlookers and was completed in 30 hours; the average speed of the steamer was 5 mph (8 km/h).

Fulton wrote to a friend, Joel Barlow:

“I had a light breeze against me the whole way, both going and coming, and the voyage has been performed wholly by the power of the steam engine. I overtook many sloops and schooners, beating to the windward, and parted with them as if they had been at anchor. The power of propelling boats by steam is now fully proved. The morning I left New York, there were not perhaps thirty persons in the city who believed that the boat would ever move one mile an hour, or be of the least utility, and while we were putting off from the wharf, which was crowded with spectators, I heard a number of sarcastic remarks. This is the way in which ignorant men compliment what they call philosophers and projectors. Having employed much time, money and zeal in accomplishing this work, it gives me, as it will you, great pleasure to see it fully answer my expectations.”

The 1870 book Great Fortunes quotes a former resident of Poughkeepsie who described the scene:

“It was in the early autumn of the year 1807 that a knot of villagers was gathered on a high bluff just opposite Poughkeepsie, on the west bank of the Hudson, attracted by the appearance of a strange, dark-looking craft, which was slowly making its way up the river. Some imagined it to be a sea-monster, while others did not hesitate to express their belief that it was a sign of the approaching judgment. What seemed strange in the vessel was the substitution of lofty and straight black smoke-pipes, rising from the deck, instead of the gracefully tapered masts that commonly stood on the vessels navigating the stream, and, in place of the spars and rigging, the curious play of the working-beam and pistons, and the slow turning and splashing of the huge and naked paddle-wheels, met the astonished gaze. The dense clouds of smoke, as they rose wave upon wave, added still more to the wonderment of the rustics.“

Scheduled passenger service began on September 4, 1807. The steamboat left New York on Saturdays at 6:00 pm, and returned from Albany on Wednesdays at 8:00 am, taking about 36 hours for each journey. Stops were made at West Point, Newburgh, Poughkeepsie, Esopus, and Hudson; other stops were sometimes made, such as Red Hook and Catskill. In the company’s publicity the ship was called North River Steamboat or just Steamboat (there being no other in operation at the time). The misnomer Clermont first appeared in Cadwallader D. Colden’s biography of Fulton, published in 1817, two years after Fulton’s death. Since Colden was a friend of both Fulton and Livingston, his book was considered an authoritative source, and his errors were perpetuated in later accounts up to the present day. The vessel is now nearly always referred to as Clermont, but no contemporary account called her by that name.

The steamer’s original 1807 federal government enrollment (registration) was lost, but because the vessel was rebuilt during the winter of 1807-1808, she had to be enrolled again. The second document lists the owners as Livingston and Fulton, and the ship’s name as North River Steamboat of Clermont.

The rebuilding of the ship was substantial: she was widened by six feet to increase navigation stability, and her simple stern tiller steering was moved forward and changed to a ship’s wheel, steering ropes, and rudder system. A poop deck and other topside additions were made or rebuilt entirely. Her exposed mid-ships engine compartment had an overhead weather deck/roof added to increase the topside deck area. Anticipating future passenger requirements, her twin paddle wheels were enclosed above the waterline to quiet their loud splashing noise, reducing heavy river mist, while also preventing floating debris from being kicked up into the vessel’s mid-hull area. Later, the ship’s long name was shortened to North River.

In its first year, the steamer differentiated itself from all of its predecessors by turning a tidy profit. The quick commercial success of North River Steamboat led Livingston and Fulton to commission in 1809 a second, very similar steamboat, Car of Neptune, followed in 1811 by Paragon. An advertisement for the passenger service in 1812 lists the three boats’ schedules, using the name North River for the firm’s first vessel. The North River was retired in 1814, and its ultimate fate remains unknown. By the time of Fulton’s death in 1815, he had built a total of seventeen steamboats, and a half-dozen more were constructed by other ship builders using his plans.

From October 1811 to January 1812, Fulton, along with Livingston and Nicholas Isaac Roosevelt, worked together on a joint project to build and travel from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on their specially designed new steamboat New Orleans. This boat was solid enough for a long trip down the mid-western Ohio River, with stops at Wheeling, Virginia, Cincinnati, Ohio, past the “Falls of the Ohio” at Louisville, Kentucky, to near Cairo, Illinois and the juncture with the Mississippi River, past St. Louis and follow the “Big Muddy” as it was acquiring the nickname, all the way down past Memphis, Tennessee and Natchez, Mississippi to the city of New Orleans on the Gulf of Mexico coast. This occurred just a decade after the United States had acquired the Louisiana Territory from France and the rivers were not well settled, mapped or protected. By achieving this first breaking voyage and also proving the ability of the boat to reverse and go back upstream, changed the entire transportation outlook for the American heartland.

Fulton’s final design was the floating battery Demologos — the world’s first steam-driven warship built for the United States Navy for the War of 1812. The heavy vessel was not completed until after his death and was renamed the Fulton in his honor.

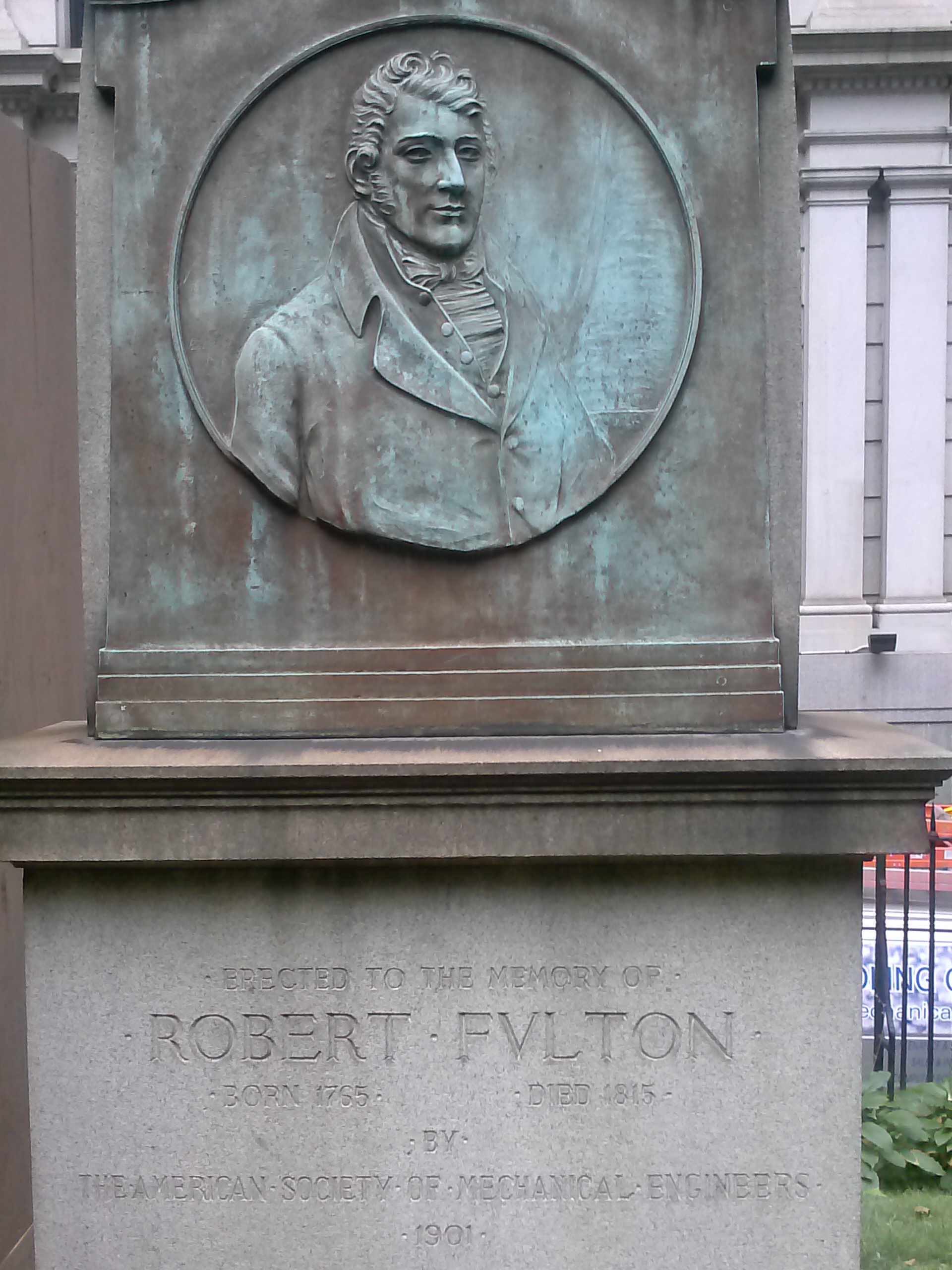

Fulton died on February 24, 1815, in New York City from tuberculosis (then known as “consumption”). He had been walking home on the frozen Hudson River when one of his friends, Addis Emmet, fell through the ice. In the attempt to rescue his friend, Fulton got soaked with icy water and on the journey home he caught pneumonia. When he got home his sickness worsened. He contracted consumption and died at 49 years old. He is buried in the Trinity Church Cemetery for Trinity Church (Episcopal) at Wall Street in New York City, alongside other famous Americans such as former U.S. Secretaries of the Treasury, Alexander Hamilton and Albert Gallatin. His descendants include former Major League Baseball pitcher Cory Lidle.

Livingston had died in 1813 and passed his shares of the steamboat company on to his sons-in-law. With Fulton’s death two years later, the original power behind the partnership dissolved. This left the company with its monopoly in New York waters prey to other ambitious American businessmen. Livingston’s heirs later granted an exclusive license to Aaron Ogden to run a ferry between New York and New Jersey, while Thomas Gibbons and Cornelius Vanderbilt established a competing service. The Livingston Fulton monopoly was dissolved in 1824 following the landmark Gibbons v. Ogden Supreme Court case, opening New York waters to all competitive steam navigation companies. In 1819, there were only nine steamboats in operation on the Hudson River; by 1840, customers could choose from more than 100 in service. The Steamboat Era had arrived.

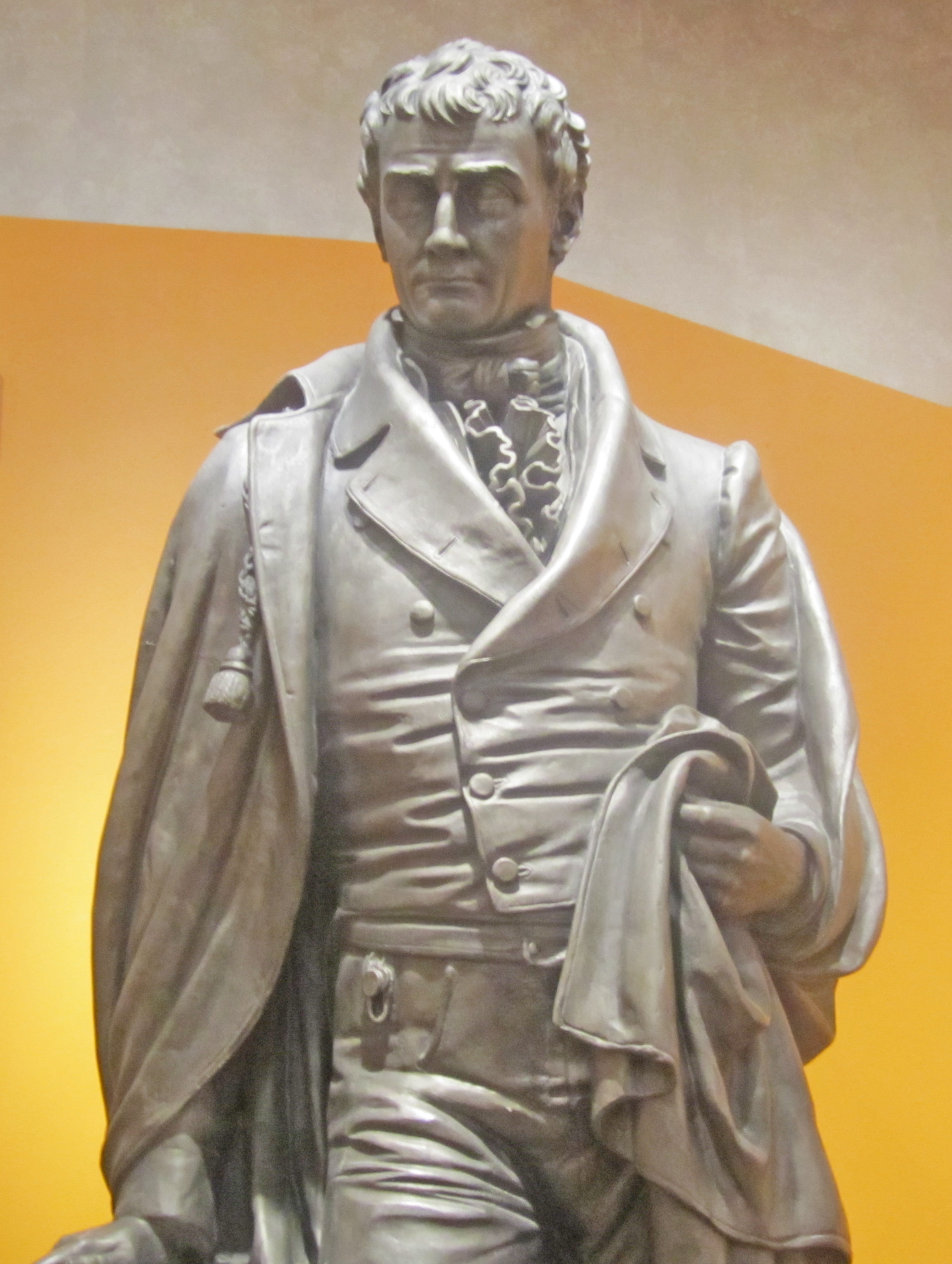

In 1816, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania donated a marble statue of Fulton to the National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol. Fulton was also honored for his development of steamship technology in New York City’s Hudson-Fulton Celebration of the Centennial in 1909. A replica of his first steam-powered steam vessel, named the Clermont, was built for the occasion.

This full-sized, 150 foot long by 16 foot wide steam-powered replica was built by the Staten Island Shipbuilding Company. The replica’s design and final appearance was decided by an appointed commission who carefully researched Fulton’s steamer from what evidence and word-of-mouth had survived to the early 20th century. Their replica was launched with great fanfare in 1909 at Staten Island, New York. In 1910, following the large celebration, Clermont was sold by her owners, the Hudson-Fulton Celebration Commission, to defray their losses. She was purchased by the Hudson River Day Line and served the company as a moored river transportation museum at their two locations in New York harbor.

In 1911, the Clermont was moved to Poughkeepsie, New York, and served Day Line as a New York state historic ship attraction. The company eventually lost interest in the steamboat as a money-making attraction and placed her in a tidal lagoon on the inner side of their landing at Kingston Point, New York. For many years, Day Line kept Clermont in presentable condition but as their business and profits slowed during the Great Depression, they voted to stop maintaining her. Clermont was eventually broken up for scrap in 1936, 27 years after her launching.

In 1940, a full-sized mock-up of the steamboat, as well as a 12-foot shooting miniature, was constructed for the Twentieth Century Fox historical film Little Old New York, The movie, based on a play by Rida Johnson Young, was a highly fictional telling of Fulton’s life from his arrival in New York to the first sailing of his steamboat. It was directed by Henry King, produced by Darryl F. Zanuck, and stars Alice Faye, Fred MacMurray, and British actor Richard Greene starring as Fulton with Brenda Joyce as Harriet Livingston. Much attention is given to Alice Faye and Fred MacMurray as wharf friends who help Fulton realize his dream amid problem after problem. The models of the steamboat constructed were based on the full-sized 1909 Clermont reproduction that had been broken up several years before.

Many places in the United States have been named for Robert Fulton and five U.S. Navy ships have borne the name USS Fulton. Bronze statues of Fulton and Christopher Columbus represent commerce on the balustrade of the galleries of the Main Reading Room in the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C. They are two of 16 historical figures, each pair representing one of the 8 pillars of civilization. In 2006, Robert Fulton was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in Alexandria, Virginia.

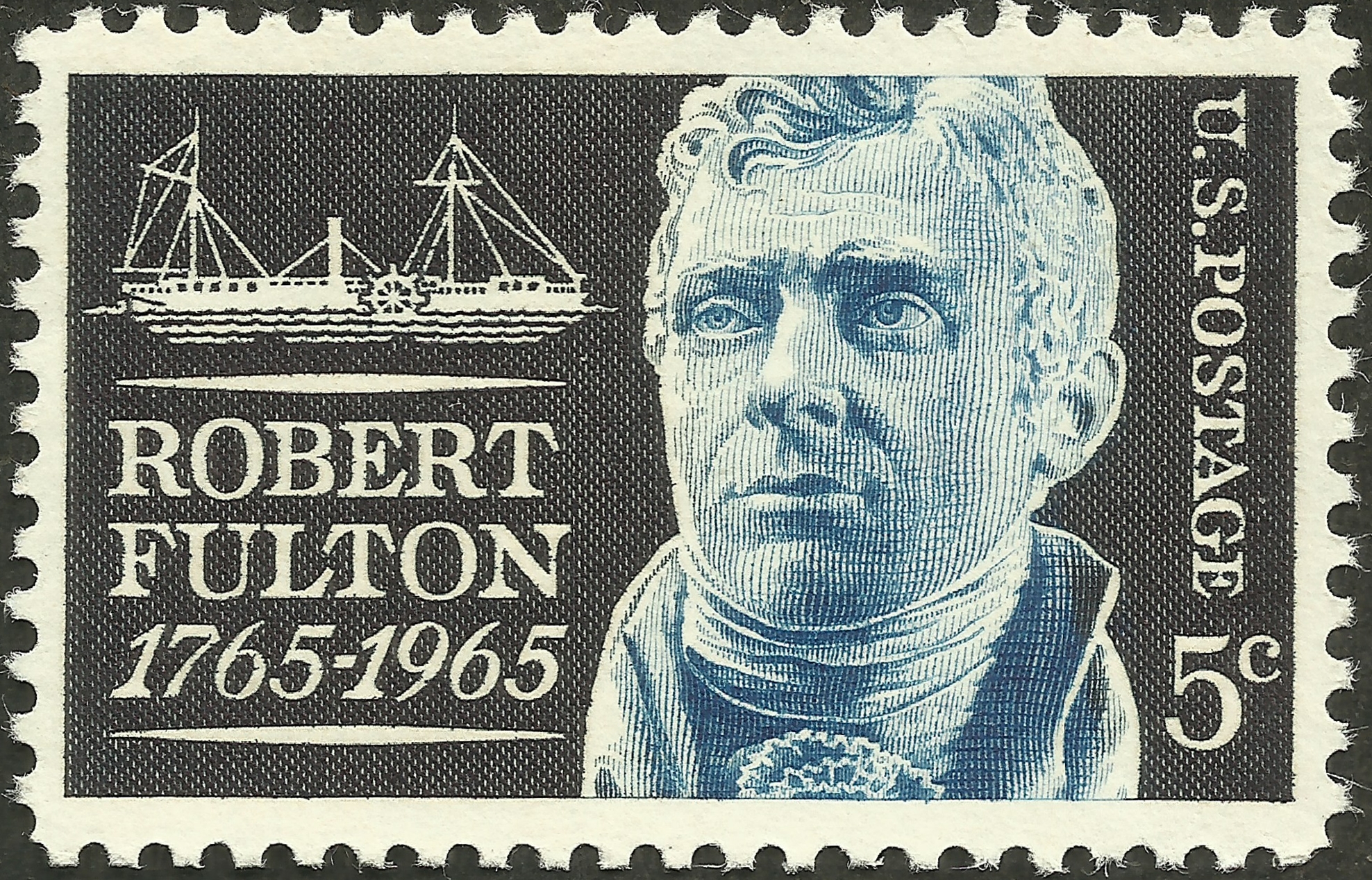

Scott #1270 was released on August 19, 1965, commemorating the 200th birth anniversary of Robert Fulton. Designed by John Maass, the 5-cent black and blue stamp features an image of a bust of Fulton sculptured by Jean Antoine Houdon and a drawing of North River Steamboat sketched to simulate wood engraving. The stamp was printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing on the Giori press and issued in panes of fifty, perforated 11. An initial printing of 114 million stamps was authorized and a total of 116,140,000 were actually issued.