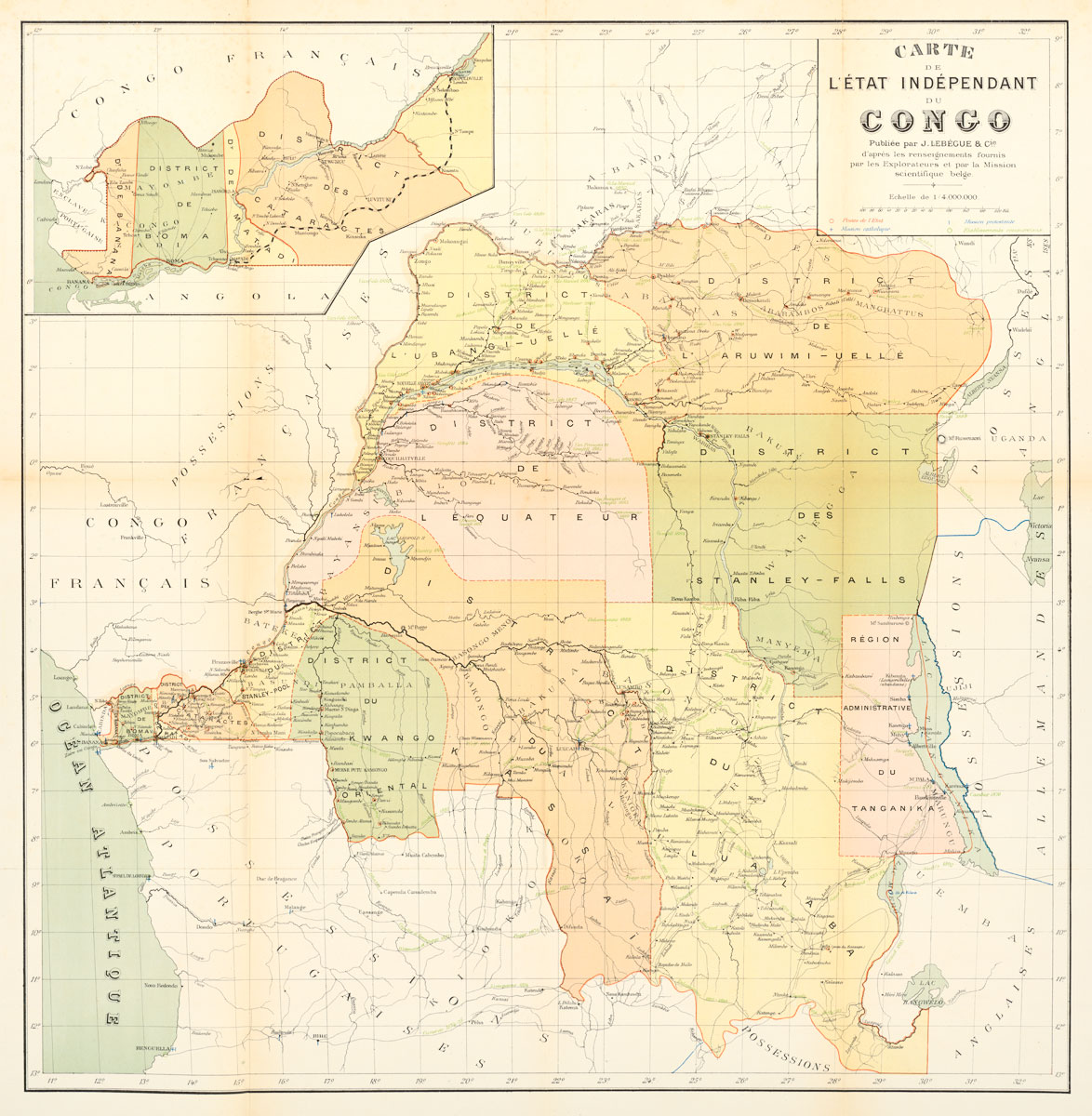

The Congo Free State (État indépendant du Congo, meaning “Independent State of the Congo”, in French, or Kongo-Vrijstaat in Dutch) was a large state in Central Africa from 1885 to 1908, which was in personal union with the Kingdom of Belgium under Leopold II. Leopold was able to procure the region by convincing the European community that he was involved in humanitarian and philanthropic work and would not tax trade. Via the International Association of the Congo he was able to lay claim to most of the Congo basin. On May 29, 1885, the king named his new colony the Congo Free State. The state would eventually include an area now held by the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Leopold’s reign in the Congo eventually earned infamy due to the increasing mistreatment of the indigenous peoples. Leopold extracted ivory, rubber, and minerals in the upper Congo basin for sale on the world market, even though his ostensible purpose in the region was to uplift the local people and develop the area. Under Leopold II’s administration, the Congo Free State became one of the greatest international scandals of the early 20th century. The report of the British Consul Roger Casement led to the arrest and punishment of white officials who had been responsible for killings during a rubber-collecting expedition in 1903.

The loss of life and atrocities inspired literature such as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, and raised an international outcry. Debate has been ongoing about the high death rate in this period. The boldest estimate concludes that the forced labor system led directly and indirectly to the deaths of 20 percent of the population. During the Congo Free State propaganda war, European and U.S. reformers exposed atrocities in the Congo Free State to the public through the Congo Reform Association, founded by Casement and the fervent humanitarian journalist E. D. Morel. Also active in exposing the activities of the Congo Free State was the author Arthur Conan Doyle, whose book The Crime of the Congo was widely read in the early 1900s.

By 1908, public pressure and diplomatic maneuvers led to the end of Leopold II’s rule and to the annexation of the Congo as a colony of Belgium. It became known thenceforth as the Belgian Congo. In addition, a number of major Belgian investment companies pushed the Belgian government to take over the Congo and develop the mining sector as it was virtually untapped.

Diogo Cão traveled around the mouth of the Congo River in 1482, leading Portugal to claim the region as England did with River Victoria. Until the middle of the 19th century, the Congo was at the heart of independent Africa, as European colonialists seldom entered the interior. Along with fierce local resistance, the rainforest, swamps, and attendant malaria, and other diseases such as sleeping sickness made it a difficult environment for Europeans to settle. Western states were at first reluctant to colonize the area in the absence of obvious economic benefits.

In 1876, Leopold II of Belgium hosted a geographic conference in Brussels, inviting famous explorers, philanthropists, and members of geographic societies to stir up interest in a “humanitarian” endeavor for Europeans to take in central Africa to “improve” and “civilize” the lives of the indigenous peoples. At the conference, Leopold organized the International African Association with the cooperation of European and American explorers and the support of several European governments, and was himself elected chairman. Leopold used the association to promote plans to seize independent central Africa under this philanthropic guise.

Henry Morton Stanley, famous for making contact with British missionary David Livingstone in Africa in 1871, later explored the region during a journey that ended in 1877 and was described in Stanley’s 1878 novel Through the Dark Continent. Failing to enlist British interest in developing the Congo region, Stanley took up service with Leopold II, who hired him to help gain a foothold in the region and annex the region for himself.

From August 1879 to June 1884, Stanley was in the Congo basin, where he built a road from the lower Congo up to Stanley Pool and launched steamers on the upper river. While exploring the Congo for Leopold, Stanley set up treaties with the local chiefs and with native leaders. Few to none of these tribal leaders had a realistic idea of what they were signing, and, in essence, the documents gave over all rights of their respective pieces of land to King Leopold II. With Stanley’s help, Leopold was able to claim a great area along the Congo River, and military posts were established.

Christian de Bonchamps, a French explorer who served Leopold in Katanga, expressed attitudes towards such treaties shared by many Europeans, saying, “The treaties with these little African tyrants, which generally consist of four long pages of which they do not understand a word, and to which they sign a cross in order to have peace and to receive gifts, are really only serious matters for the European powers, in the event of disputes over the territories. They do not concern the black sovereign who signs them for a moment.”

Leopold began to create a plan to convince other European powers of the legitimacy of his claim to the region, all the while maintaining the guise that his work was for the benefit of the native peoples under the name of a philanthropic “association”.

The king launched a publicity campaign in Britain to distract critics, drawing attention to Portugal’s record of slavery, and offering to drive slave traders from the Congo basin. He also secretly told British merchant houses that if he was given formal control of the Congo for this and other humanitarian purposes, he would then give them the same most favored nation (MFN) status Portugal had offered them. At the same time, Leopold promised Bismarck he would not give any one nation special status, and that German traders would be as welcome as any other.

Leopold then offered France the support of the association for French ownership of the entire northern bank of the Congo, and sweetened the deal by proposing that, if his personal wealth proved insufficient to hold the entire Congo, as seemed utterly inevitable, that it should revert to France.

He also enlisted the aid of the United States, sending President Chester A. Arthur carefully edited copies of the cloth-and-trinket treaties British explorer Henry Morton Stanley claimed to have negotiated with various local authorities, and proposing that, as an entirely disinterested humanitarian body, the association would administer the Congo for the good of all, handing over power to the locals as soon as they were ready for that responsibility.

Leopold was able to attract scientific and humanitarian backing for the International African Association (Association internationale africaine, or AIA), which he formed during a Brussels Geographic Conference of geographic societies, explorers, and dignitaries he hosted in 1876. At the conference, Leopold proposed establishing an international benevolent committee for the propagation of civilization among the peoples of central Africa (the Congo region). Originally conceived as a multi-national, scientific, and humanitarian assembly, the AIA eventually became a development company controlled by Leopold.

After 1879 and the crumbling of the International African Association, Leopold’s work was done under the auspices of the “Committee for Studies of the Upper Congo” (Comité d’Études du Haut-Congo). The committee, supposedly an international commercial, scientific, and humanitarian group, was in fact made of a group of businessmen who had shares in the Congo, with Leopold holding a large block by proxy. The committee itself eventually disintegrated, but Leopold continued to refer to it and use the defunct organization as a smokescreen for his operations in laying claim to the Congo region.

Determined to look for a colony for himself and inspired by recent reports from central Africa, Leopold began patronizing a number of leading explorers, including Henry Morton Stanley. Leopold established the International African Association, a charitable organization to oversee the exploration and surveying of a territory based around the Congo River, with the stated goal of bringing humanitarian assistance and civilization to the natives. In the Berlin Conference of 1884–85, European leaders officially noted Leopold’s control over the 1,000,000 square miles (2,600,000 km²) of the notionally-independent Congo Free State.

To give his African operations a name that could serve for a political entity, Leopold created, between 1879 and 1882, the International Association of the Congo (Association internationale du Congo, or AIC) as a new umbrella organization. This organization sought to combine the numerous small territories acquired into one sovereign state and asked for recognition from the European powers. On April 22, 1884, thanks to the successful lobbying of businessman Henry Shelton Sanford at Leopold’s request, President Chester A. Arthur of the United States decided that the cessions claimed by Leopold from the local leaders were lawful and recognized the International Association of the Congo’s claim on the region, becoming the first country to do so. In 1884, the U.S. Secretary of State said, “The Government of the United States announces its sympathy with and approval of the humane and benevolent purposes of the International Association of the Congo.”

In November 1884, Otto von Bismarck convened a 14-nation conference to submit the Congo question to international control and to finalize the colonial partitioning of the African continent. Most major powers (including Austria-Hungary, Belgium, France, Germany, Portugal, Italy, Great Britain, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, and the United States) attended the Berlin Conference, and drafted an international code governing the way that European countries should behave as they acquired African territory. The conference officially recognized the International Congo Association, and specified that it should have no connection with Belgium or any other country, but would be under the personal control of King Leopold, i.e., personal union.

It drew specific boundaries and specified that all nations should have access to do business in the Congo with no tariffs. The slave trade would be suppressed. In 1885, Leopold emerged triumphant. France was given 257,000 square miles (666,000 km²) on the north bank (the modern Congo-Brazzaville and Central African Republic), Portugal 351,000 square miles (909,000 km²) to the south (modern Angola), and Leopold’s personal organisation received the balance: 905,000 square miles (2,344,000 km²), with about 30 million people. However, it still remained for these territories to be occupied under the conference’s “Principle of Effective Occupation”.

Following the United States’s recognition of Leopold’s colony, other European powers deliberated on the news. Portugal flirted with the French at first, but the British offered to support Portugal’s claim to the entire Congo in return for a free trade agreement and to spite their French rivals. Britain was uneasy at French expansion and had a technical claim on the Congo via Lieutenant Cameron’s 1873 expedition from Zanzibar to bring home Livingstone’s body, but was reluctant to take on yet another expensive, unproductive colony. Bismarck of Germany had vast new holdings in southwest Africa, and had no plans for the Congo, but was happy to see rivals Britain and France excluded from the colony.

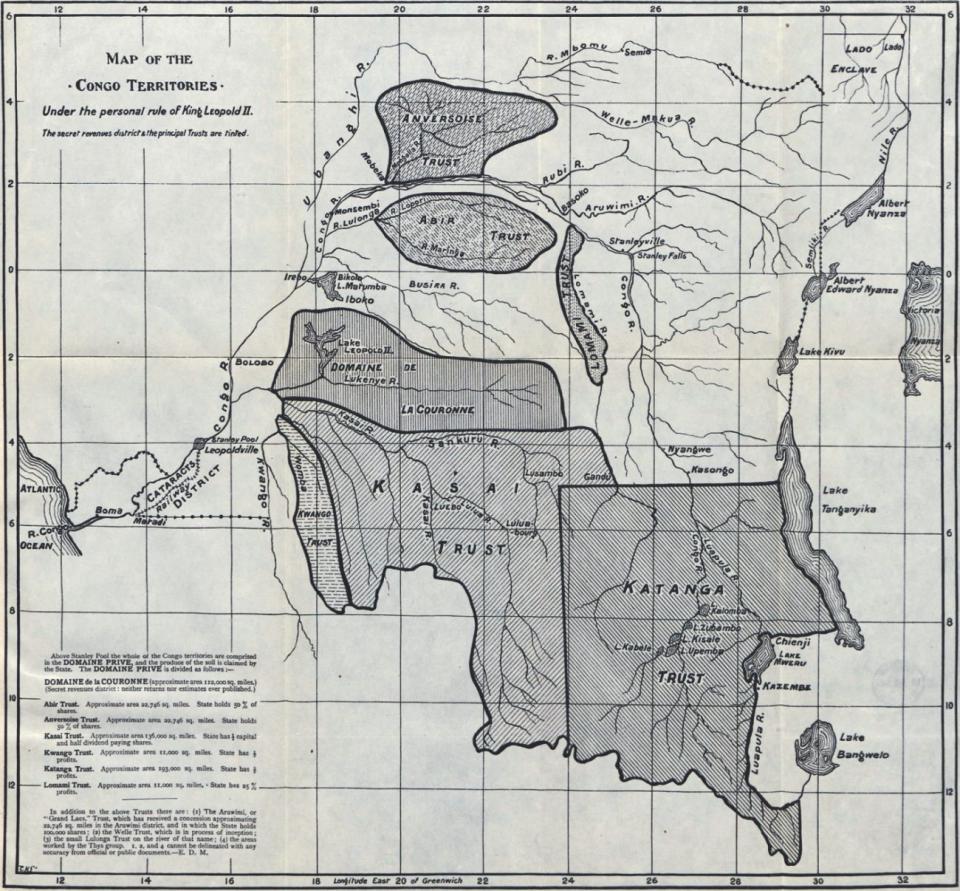

In 1885, Leopold’s efforts to establish Belgian influence in the Congo Basin were awarded with the État Indépendant du Congo (CFS, Congo Free State). By a resolution passed in the Belgian parliament, Leopold became roi souverain, sovereign king, of the newly formed CFS, over which he enjoyed nearly absolute control. The CFS became Leopold’s personal property, the Domaine Privé.

Leopold used the title Sovereign King as ruler of the Congo Free State. He appointed the heads of the three departments of state: interior, foreign affairs and finances. Each was headed by an administrator-general (administrateur-général), later a secretary-general (secrétaire-général), who was obligated to enact the policies of the sovereign or else resign. Below the secretaries-general were a series of bureaucrats of decreasing rank: directors general (directeurs généraux), directors (directeurs), chefs de divisions (division chiefs) and chefs de bureaux (bureau chiefs). The departments were headquartered in Brussels.

Finance was in charge of accounting for income and expenditure and tracking the public debt. Besides diplomacy, foreign affairs was in charge of shipping, education, religion and commerce. The department of the interior was responsible for defense, police, public health and public works. It was also charged with overseeing the exploitation of the Congo’s natural resources and plantations. In 1904, the secretary-general of the interior set up a propaganda office, the Bureau central de la presse (“Central Press Bureau”), in Frankfurt under the auspices of the Comité pour la représentation des intérêts coloniaux en Afrique (in German, Komitee zur Wartung der Interessen in Afrika, “Committee for the Representation of Colonial Interests in Africa”).

The oversight of all the departments was nominally in the hands of the Governor-General (Gouverneur général), but this office was at times more honorary than real. When the governor-general was in Belgium he was represented in the Congo by a vice governor-general (vice-gouverneur général), who was nominally equal in rank to a secretary-general but in fact was beneath them in power and influence. A Comité consultatif (consultative committee) made up of civil servants was set up in 1887 to assist the governor-general, but he was not obliged to consult it. The vice governor-general on the ground had a state secretary through whom he communicated with his district officers.

The Free State had an independent judiciary headed by a minister of justice at Boma. The minister was equal in rank to the vice governor-general and initially answered to the governor-general, but was eventually made responsible to the sovereign alone. There was a supreme court composed of three judges, which heard appeals, and below it a high court of one judge. These sat at Boma. In addition to these, there were district courts and public prosecutors (procureurs d’état). Justice, however, was slow and the system ill-suited to a frontier society.

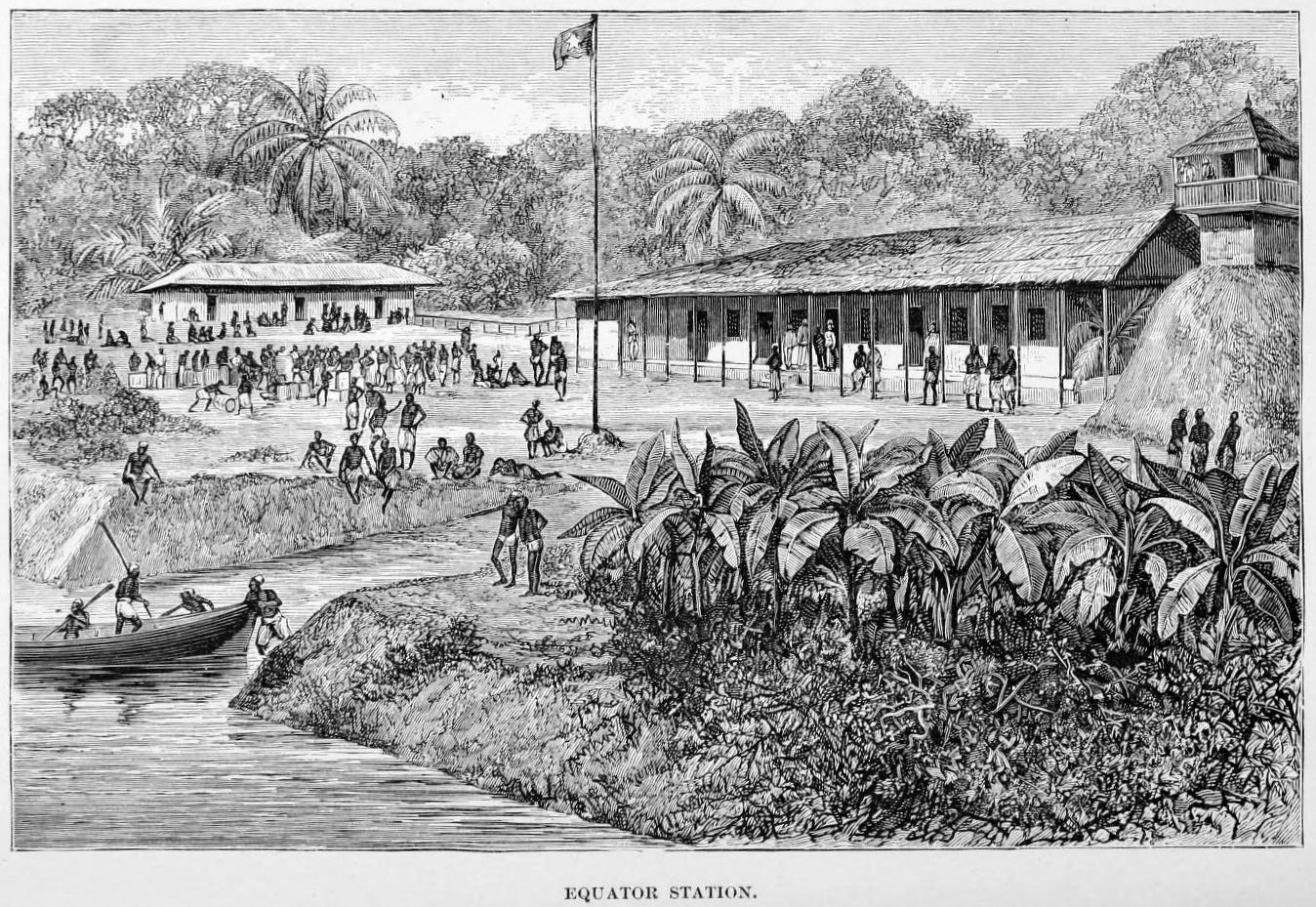

Leopold no longer needed the façade of the association, and replaced it with an appointed cabinet of Belgians who would do his bidding. To the temporary new capital of Boma, he sent a governor-general and a chief of police. The vast Congo basin was split up into 14 administrative districts, each district into zones, each zone into sectors, and each sector into posts. From the district commissioners down to post level, every appointed head was European. However, with little financial means the Free State mainly relied on local elites to rule and tax the vast and hard-to-reach Congolese interior.

Leopold pledged to suppress the east African slave trade; promote humanitarian policies; guarantee free trade within the colony; impose no import duties for twenty years; and encourage philanthropic and scientific enterprises. Beginning in the mid-1880s, Leopold first decreed that the state asserted rights of proprietorship over all vacant lands throughout the Congo territory. In three successive decrees, Leopold promised the rights of the Congolese in their land to native villages and farms, essentially making nearly all of the CFS terres domainales (state-owned land). Leopold further decreed that merchants should limit their commercial operations in rubber trade with the natives. Additionally, the colonial administration liberated thousands of slaves.

Leopold could not meet the costs of running the Congo Free State. Desperately, he set in motion a system to maximize revenue. The first change was the introduction of the concept of terres vacantes, “vacant” land, which was any land that did not contain a habitation or a cultivated garden plot. All of this land (i.e., most of the country) was therefore deemed to belong to the state. Servants of the state (namely any men in Leopold’s employ) were encouraged to exploit it.

Shortly after the anti-slavery conference he held in Brussels in 1889, Leopold issued a new decree which said that Africans could only sell their harvested products (mostly ivory and rubber) to the state in a large part of the Free State. This law grew out of the earlier decree which had said that all “unoccupied” land belonged to the state. Any ivory or rubber collected from the state-owned land, the reasoning went, must belong to the state; creating a de facto state-controlled monopoly. Suddenly, the only outlet a large share of the local population had for their products was the state, which could set purchase prices and therefore could control the amount of income the Congolese could receive for their work. However, for local elites this system presented new opportunities as the Free State and concession companies paid them with guns to tax their subjects in kind.

Trading companies began to lose out to the free state government, which not only paid no taxes but also collected all the potential income. These companies were outraged by the restrictions on free trade, which the Berlin Act had so carefully protected years before.[21] Their protests against the violation of free trade prompted Leopold to take another, less obvious tack to make money.

A decree in 1892 divided the terres vacantes into a domainal system, which privatized extraction rights over rubber for the state in certain private domains, allowing Leopold to grant vast concessions to private companies. In other areas, private companies could continue to trade but were highly restricted and taxed. The domainal system enforced an in-kind tax on the Free State’s Congolese subjects. As essential intermediaries, local rulers forced their men, women and children to collect rubber, ivory and foodstuffs. Depending on the power of local rulers, the Free State paid below rising market prices. In October 1892, Leopold granted concessions to a number of companies. Each company was given a large amount of land in the Congo Free State on which to collect rubber and ivory for sale in Europe. These companies were allowed to detain Africans who did not work hard enough, to police their vast areas as they saw fit and to take all the products of the forest for themselves. In return for their concessions, these companies paid an annual dividend to the Free State. At the height of the rubber boom, from 1901 until 1906, these dividends also filled the royal coffers.

The Free Trade Zone in the Congo was open to entrepreneurs of any European nation, who were allowed to buy 10- and 15-year monopoly leases on anything of value: ivory from a district or the rubber concession, for example. The other zone — almost two-thirds of the Congo — became the Domaine Privé, the exclusive private property of the state.

In 1893, Leopold excised the most readily accessible 100,000 square mile (259,000 km²) portion of the Free Trade Zone and declared it to be the Domaine de la Couronne, literally, “fief of the crown”. Rubber revenue went directly to Leopold who paid the Free State for the high costs of exploitation. The same rules applied as in the Domaine Privé. In 1896, global demand for rubber soared. From that year onwards, the Congolese rubber sector started to generated vast sums of money at an immense cost for the local population.

While the war against African powers was ending, the quest for income was increasing, fueled by the aire policy. By 1890, Leopold was facing considerable financial difficulty. District officials’ salaries were reduced to a bare minimum, and made up with a commission payment based on the profit that their area returned to Leopold. After widespread criticism, this “primes system” was substituted for the allocation de retraite in which a large part of the payment was granted, at the end of the service, only to those territorial agents and magistrates whose conduct was judged “satisfactory” by their superiors. This meant in practice that nothing changed. Congolese communities in the Domaine Privé were not merely forbidden by law to sell items to anyone but the state; they were required to provide state officials with set quotas of rubber and ivory at a fixed, government-mandated price and to provide food to the local post.

In direct violation of his promises of free trade within the CFS under the terms of the Berlin Treaty, not only had the state become a commercial entity directly or indirectly trading within its dominion, but also, Leopold had been slowly monopolizing a considerable amount of the ivory and rubber trade by imposing export duties on the resources traded by other merchants within the CFS. In terms of infrastructure, Leopold’s regime began construction of the railway that ran from the coast to the capital of Leopoldville (now Kinshasa). This project, known today as the Matadi–Kinshasa Railway, took years to complete.

By the final decade of the 19th century, John Boyd Dunlop’s 1887 invention of inflatable, rubber bicycle tubes and the growing popularity of the automobile dramatically increased global demand for rubber. To monopolize the resources of the entire Congo Free State, Leopold issued three decrees in 1891 and 1892 that reduced the native population to serfs. Collectively, these forced the natives to deliver all ivory and rubber, harvested or found, to state officers thus nearly completing Leopold’s monopoly of the ivory and rubber trade. The rubber came from wild vines in the jungle, unlike the rubber from Brazil (Hevea brasiliensis), which was tapped from trees. To extract the rubber, instead of tapping the vines, the Congolese workers would slash them and lather their bodies with the rubber latex. When the latex hardened, it would be scraped off the skin in a painful manner, as it took off the worker’s hair with it.

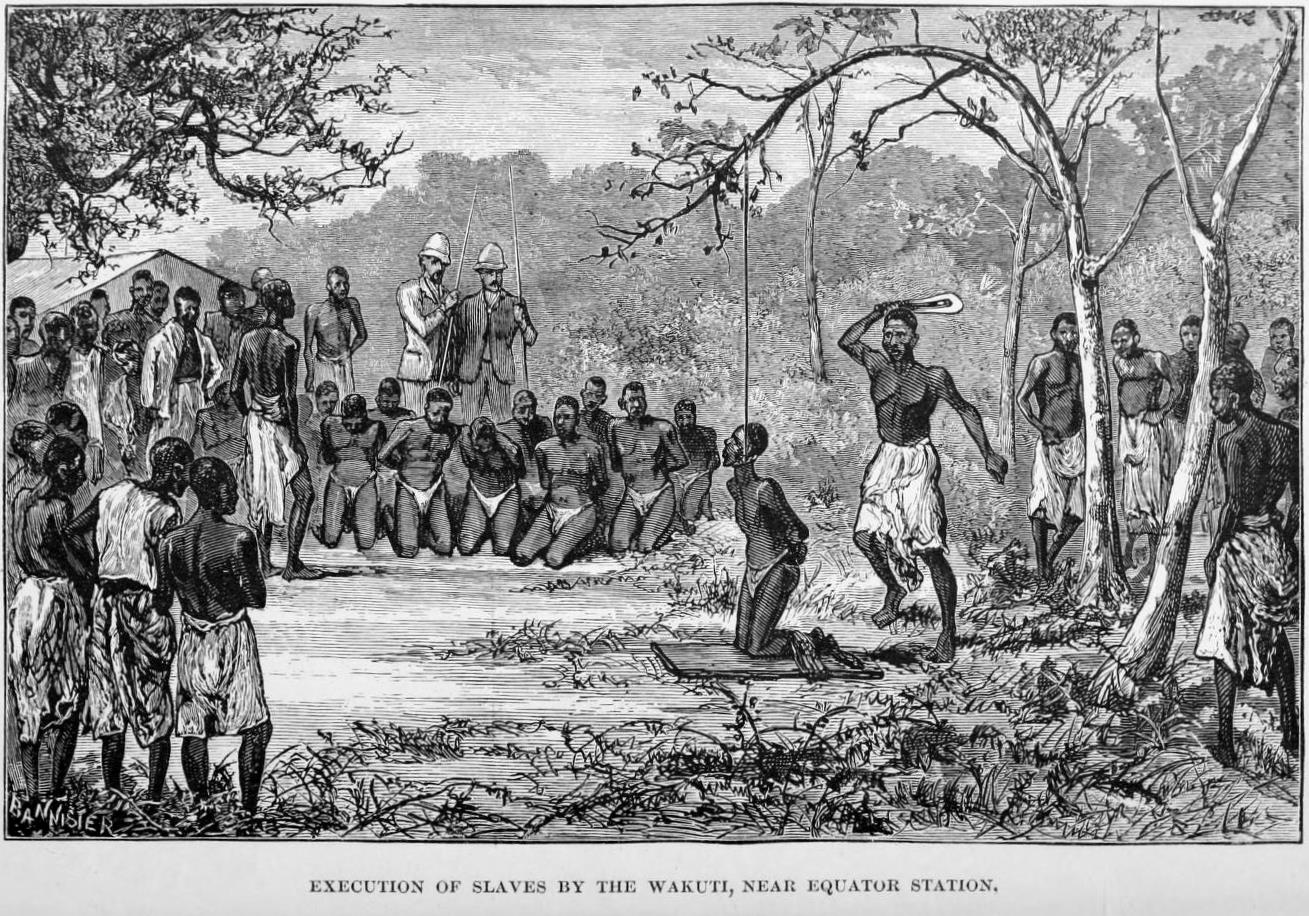

The Force Publique (FP), Leopold’s private army, was used to enforce the rubber quotas. Early on, the FP was used primarily to campaign against the Arab slave trade in the Upper Congo, protect Leopold’s economic interests, and suppress the frequent uprisings within the state. The Force Publique‘s officer corps included only white Europeans (Belgian regular soldiers and mercenaries from other countries). On arriving in the Congo, these recruited men from Zanzibar and west Africa, and eventually from the Congo itself. In addition, Leopold had been actually encouraging the slave trade among Arabs in the Upper Congo in return for slaves to fill the ranks of the FP. During the 1890s, the FP’s primary role was to exploit the natives as corvée laborers to promote the rubber trade.

Many of the black soldiers were from far-off peoples of the Upper Congo, while others had been kidnapped in raids on villages in their childhood and brought to Roman Catholic missions, where they received a military training in conditions close to slavery. Armed with modern weapons and the chicotte — a bull whip made of hippopotamus hide — the Force Publique routinely took and tortured hostages, slaughtered families of rebels, and flogged and raped Congolese people. They also burned recalcitrant villages, and above all, cut off the hands of Congolese natives, including children. The human hands were collected as trophies on the orders of their officers to show that bullets hadn’t been wasted. Officers were concerned that their subordinates might waste their ammunition on hunting animals for sport, so they required soldiers to submit one hand for every bullet spent. These mutilations also served to further terrorize the Congolese into submission. This was all contrary to the promises of uplift made at the Berlin Conference which had recognized the Congo Free State.

Failure to meet the rubber collection quotas was punishable by death. Meanwhile, the Force Publique were required to provide the hand of their victims as proof when they had shot and killed someone, as it was believed that they would otherwise use the munitions (imported from Europe at considerable cost) for hunting. As a consequence, the rubber quotas were in part paid off in chopped-off hands. Sometimes the hands were collected by the soldiers of the Force Publique, sometimes by the villages themselves. There were even small wars where villages attacked neighboring villages to gather hands, since their rubber quotas were too unrealistic to fill. A Catholic priest quotes a man, Tswambe, speaking of the hated state official Léon Fiévez, who ran a district along the river 300 miles (500 km) north of Stanley Pool:

“All blacks saw this man as the devil of the Equator…From all the bodies killed in the field, you had to cut off the hands. He wanted to see the number of hands cut off by each soldier, who had to bring them in baskets…A village which refused to provide rubber would be completely swept clean. As a young man, I saw [Fiévez’s] soldier Molili, then guarding the village of Boyeka, take a net, put ten arrested natives in it, attach big stones to the net, and make it tumble into the river…Rubber causes these torments; that’s why we no longer want to hear its name spoken. Soldiers made young men kill or rape their own mothers and sisters.“

One junior European officer described a raid to punish a village that had protested. The European officer in command “ordered us to cut off the heads of the men and hang them on the village palisades … and to hang the women and the children on the palisade in the form of a cross.” After seeing a Congolese person killed for the first time, a Danish missionary wrote, “The soldier said ‘Don’t take this to heart so much. They kill us if we don’t bring the rubber. The Commissioner has promised us if we have plenty of hands he will shorten our service.'” In Forbath’s words:

“The baskets of severed hands, set down at the feet of the European post commanders, became the symbol of the Congo Free State. … The collection of hands became an end in itself. Force Publique soldiers brought them to the stations in place of rubber; they even went out to harvest them instead of rubber… They became a sort of currency. They came to be used to make up for shortfalls in rubber quotas, to replace… the people who were demanded for the forced labour gangs; and the Force Publique soldiers were paid their bonuses on the basis of how many hands they collected.“

In theory, each right hand proved a killing. In practice, soldiers sometimes “cheated” by simply cutting off the hand and leaving the victim to live or die. More than a few survivors later said that they had lived through a massacre by acting dead, not moving even when their hands were severed, and waiting till the soldiers left before seeking help. In some instances a soldier could shorten his service term by bringing more hands than the other soldiers, which led to widespread mutilations and dismemberment.

A reduction of the population of the Congo is noted by all who have compared the country at the beginning of Leopold’s control with the beginning of Belgian state rule in 1908, but estimates of the death toll vary considerably. Estimates of contemporary observers suggest that the population decreased by half during this period and these are supported by some modern scholars such as Jan Vansina. Others dispute this. Scholars at the Royal Museum for Central Africa which Leopold II founded argue a decrease of 20 percent over the first forty years of colonial rule (up to the census of 1924).

According to British diplomat Roger Casement, this depopulation had four main causes: “indiscriminate war”, starvation, reduction of births, and disease. Sleeping sickness was also a major cause of fatality at the time. Opponents of Leopold’s rule stated, however, that the administration itself was to be considered responsible for the spreading of the epidemic.

In the absence of a census providing even an initial idea of the size of population of the region at the inception of the Congo Free State (the first was taken in 1924), it is impossible to quantify population changes in the period. Despite this, Forbath claimed the loss was at least five million Adam Hochschild, and Isidore Ndaywel è Nziem, 10 million; no verifiable records exist. Louis and Stengers state that population figures at the start of Leopold’s control are only “wild guesses”, while calling E.D. Morel’s attempt and others at coming to a figure for population losses “but figments of the imagination”.

Nevertheless, Hochschild cites several recent independent lines of investigation, by anthropologist Jan Vansina and others, that examine local sources (police records, religious records, oral traditions, genealogies, personal diaries), which generally agree with the assessment of the 1919 Belgian government commission: roughly half the population perished during the Free State period. Since the first official census by the Belgian authorities in 1924 put the population at about 10 million, these various approaches suggest a rough estimate of a total of 10 million dead. To put these population changes in context, sourced references state that in 1900 Africa as a whole had between 90 million and 133 million people.

Leopold ran up high debts with his Congo investments before the beginning of the worldwide rubber boom in the 1890s. Prices increased throughout the decade as industries discovered new uses for rubber in tires, hoses, tubing, insulation for telegraph and telephone cables and wiring. By the late-1890s, wild rubber had far surpassed ivory as the main source of revenue from the Congo Free State. The peak year was 1903, with rubber fetching the highest price and concessionary companies raking in the highest profits.

However, the boom sparked efforts to find lower-cost producers. Congolese concessionary companies started facing competition from rubber cultivation in Southeast Asia and Latin America. As plantations were begun in other tropical areas — mostly under the ownership of the rival British firms — world rubber prices started to dip. Competition heightened the drive to exploit forced labor in the Congo in order to lower production costs. Meanwhile, the cost of enforcement was eating away at profit margins, along with the toll taken by the increasingly unsustainable harvesting methods. As competition from other areas of rubber cultivation mounted, Leopold’s private rule was left increasingly vulnerable to international scrutiny.

Missionaries were allowed only on sufferance, and Leopold was able to silence the Belgian Catholics. Rumors circulated so Leopold attempted to discredit them, even creating a Commission for the Protection of the Natives. Publishers were bribed, critics accused of running secret campaigns to further other nations’ colonial ambitions, and eyewitness reports from missionaries such as William Henry Sheppard dismissed as attempts by Protestants to smear Catholic priests. For at least a decade, criticism was largely contained.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, originally published in 1899 as a three-part series in Blackwood’s Magazine, based on a brief experience as a steamer captain on the Congo 12 years before, sparked an organized international opposition to Leopold’s genocidal activities, which mobilized. In 1900, Edmund Dene Morel, a part-time journalist and head of trade with Congo for the Liverpool shipping firm Elder Dempster, noticed that ships that brought vast loads of rubber from the Congo only ever returned there loaded with guns and ammunition for the Force Publique. Morel became a journalist and then a publisher, attempting to discredit Leopold’s regime. In 1902, Morel retired from his position at Elder Dempster to focus on campaigning. He founded his own magazine, The West African Mail, and conducted speaking tours in Britain.

Increasing public outcry over the atrocities in the CFS moved the British government to launch an official investigation. In 1903, Morel and those who agreed with him in the House of Commons succeeded in passing a resolution calling on the British government to conduct an inquiry into alleged violations of the Berlin Agreement. Roger Casement, then the British Consul at Boma (at the mouth of the Congo River), was sent to the Congo Free State to investigate. Reporting back to the Foreign Office in 1900, Casement wrote

“The root of the evil lies in the fact that the government of the Congo is above all a commercial trust, that everything else is orientated towards commercial gain...”

The Congo Reform Association (CRA) was established in Great Britain by Morel as a direct result of Casement’s 1904 detailed, eyewitness Congo report, known as the Casement Report. The Congo Reform movement’s members included Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Mark Twain, Joseph Conrad, Booker T. Washington, and Bertrand Russell.

The mass deaths in the Congo Free State became a cause célèbre in the last years of the 19th century. The Congo reform movement led a vigorous international movement against the maltreatment of the Congolese population. The British Parliament demanded a meeting of the 14 signatory powers to review the 1885 Berlin Agreement. The Belgian Parliament, pushed by Emile Vandervelde and other critics of the king’s Congolese policy, forced Leopold to set up an independent commission of inquiry, and despite the king’s efforts, in 1905 it confirmed Casement’s report.

Leopold offered to reform his regime, but international opinion supported an end to the king’s rule, and no nation was willing to accept this responsibility. Belgium was the obvious European candidate to run the Congo. For two years, it debated the question and held new elections on the issue.

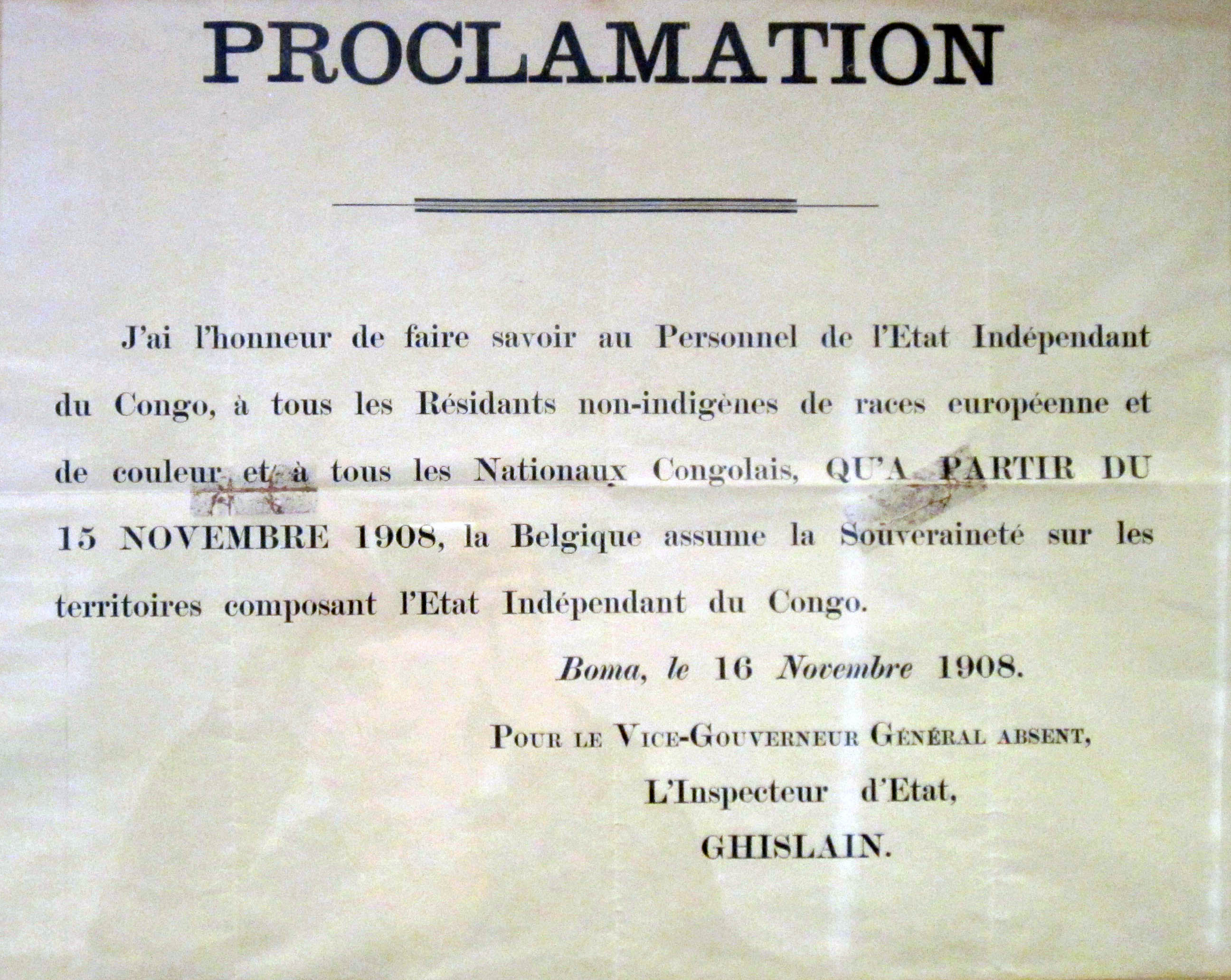

Yielding to international pressure, the parliament of Belgium annexed the Congo Free State and took over its administration on November 15, 1908, as the colony of the Belgian Congo. Despite being effectively removed from power, the international scrutiny was no major loss to Leopold or the concessionary companies in the Congo. By then Southeast Asia and Latin America had become lower-cost producers of rubber. Along with the effects of resource depletion in the Congo, international commodity prices had fallen to a level that rendered Congolese extraction unprofitable. Just prior to releasing sovereignty over the CFS, Leopold had all evidence of his activities in the CFS destroyed, including the archives of the departments of finance and of the interior. Leopold lost the absolute power he had had there, but the population still had a Belgian colonial regime, which had become heavily paternalistic, with church, state, and private companies all instructed to oversee the welfare of the inhabitants.

The first stamps of the Congo Free State were issued on January 1, 1896, a set of five featuring the left-facing profile of King Leopold II, copying the Belgian definitives of 1869 (Scott #1-5). These are listed in the Scott catalogue at the beginning of the Belgian Congo listings, designated “Independent State”. Only 4800 copies of the 5-franc lilac high value (Scott #5) were printed, many of which were overprinted COLIS POSTAUX Fr 3.50 for parcel post usage (Scott #Q1).

Between 1887 and 1894, a set of eight definitives were released with the slightly right-facing ¾ profile of Leopold II, his huge beard prominent (Scott #6-13). The 5-franc violet stamps of this issue were also overprinted for parcel post use and are quite scarce (Scott #Q3-Q4) as was the 5-franc grey (Scott #Q6). Inverted surcharges also exist of each of the parcel post stamps and counterfeits abound. The 10-franc buff stamp was largely used for fiscal purposes, although occasionally there was some postage usage. Counterfeits exist for all of these early CFS stamps including genuine stamps with faked cancels and counterfeit stamps with genuine cancels.

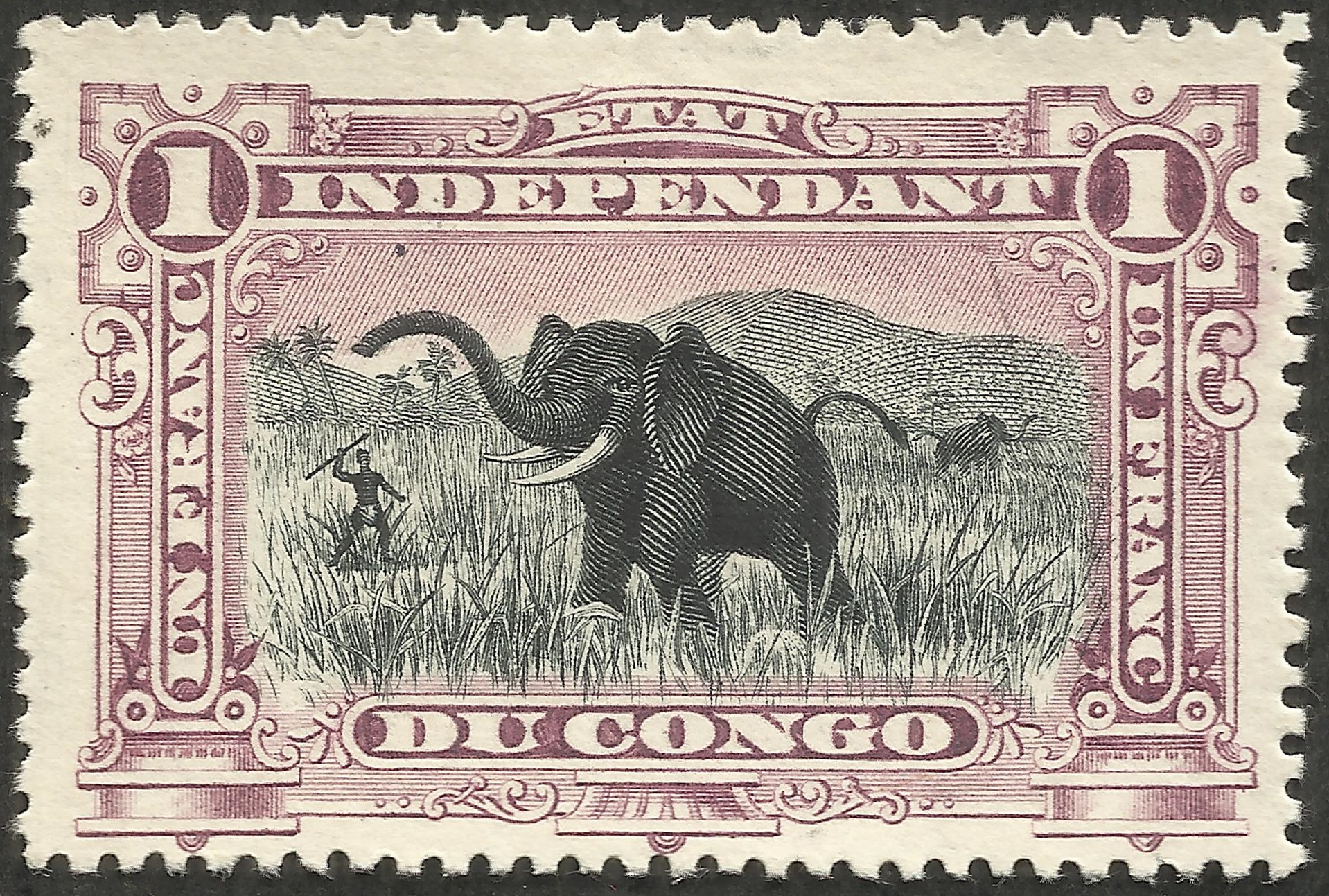

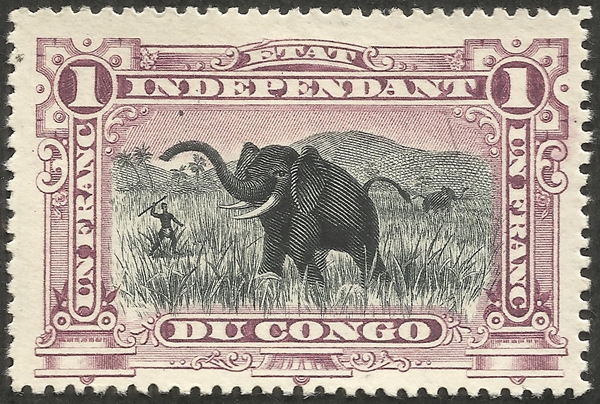

A set of 17 beautifully-engraved bicolored stamps showing scenes of the Congo was released beginning in November 1894 and continuing until 1901. (Scott #14-30). These are collectively known as the “Mols” issue because the designs were based on a diorama exhibition created by Robert Mols and Piet van Engelen for the Antwerp Exposition of 1894. The Mol stamps all have brightly colored frames with black vignettes.

Most of the Mols were printed by Waterlow and Sons of London, England, but the two high value stamps issued in 1898 were printed by Waterlow Bros & Layton of London (Scott #29-30). The perforations gauge in a range from 12½ to 15. Both the 5- and 10-centimes stamps were bought up by stamp dealers in Belgium and saw very little actual postal usage.

The 5-centime stamps with a black center and frames of pale blue portrayed Port Matadi (Scott #14) while the 10-centime stamps had black centers and frames printed in red brown featured a river scene on the Congo with Stanley Falls in the background (Scott #17). Inkissi Falls was pictured on the 25-centime stamps with yellow orange frames (Scott #20). The 50-centime values with green frames (Scott #22) — bear a railroad bridge on the M’pozo River while “hunting elephants” is the image featured on the 1 franc stamps of 1894 with a lilac frame (Scott #24); a rose lilac frame variety also exists (Scott #24a). The 5-franc stamp with lake frame and black vignette portrays a Bangala chief and his wife (Scott #26). A carmine rose frame variety has been relegated to a sub-number in Scott (#26a).

The 15- and 40-centime stamps were issued in November 1896 and picture “climbing oit palms” (ocher frame) and a Congo canoe (bluish green frame), respectively (Scott #27-28). The 5- and 10-centime values were issued in new frame colors (red brown and greenish blue) in January 1895 (Scott #15 and #18).

In May 1898, the 3.50-franc stamp was issued primarily for parcel post usage; it had a red frame and pictured a Bantu village (Scott #29). At the same time, the high value of 10 francs was released with a yellow green frame and described by Scott as a “river steamer on the Congo” (Scott #30). This is the Deliverance, an iron-decked, 65-foot paddle wheel steamer with a draft of just three feet that allowed it to travel far up the Congo River’s many tributaries. There was a tiny two-berth passenger cabin amidships. The wood stoked furnaces and boiler were forward, and the engines were in the stern. The upper deck at the bow of the ship held the captain’s cabin and the bridge. This combination served as the dining area for both the captain and the passengers. The Deliverance inverted center error stamp is one of the most spectacular and valuable classic stamps (Scott #30a). In 2008, the Scott Classic Specialized Catalogue valued this stamp at U.S. $25,000 in unused, hinged condition.

In May 1900, all of the centime values originally issued in 1894 were released in new colors to conform with the guidelines of the Universal Postal Union. The 5 centimes stamp now had a frame of green (Scott #16), the 10 centimes denomination had a carmine frame (Scott #19), the frame of the 25 centimes value was changed to light blue (Scott #21) while the 50-centime stamp sported a olive green frame (Scott #23). The final release of the Congo Free State was a frame color change to carmine on the 1-franc stamp appearing in 1901 (Scott #25).

Beginning on January 1, 1900, existing stocks of the Congo Free State “Mols” inscribed Etat Independent du Congo were overprinted CONGO BELGE by handstamp (Scott #31-40). Eight different handstamps were in use in Brussels but few of these actually found their way to the newly-named Belgian Congo and are scarce postally used. Using the “type V” handstamp as a model, a typographed overprint was prepared and applied, also in Belgium, Additionally, there were eight different handstamps applied in the Congo. An official reprint of several of these handstamps was released in March 1909 with slight differences to the originals; many of these were postally used. That June, four designs of the “Mol” stamps were released inscribed CONGO BELGE and known as the “Monlingual Issue” (Scott #41-44). Additional stamps using the same designs as the original Congo Free Stamp “Mols” were released between 1910 and 1915 inscribed CONGO BELGE / BELGISCH CONGO or the “Bilingual Issue” (Scott #45-62). The stamps released in 1915 included a retouching of the center plates of all the centimes values.

The stamps appeared again in 1918 with blue centers and a surcharge for the benefit of the Red Cross (Scott #B1-B9). The position of the cross and the added value varies on the different stamps. These also exist imperforate without gum.

When Belgium was invaded in World War I, considerable quantities of the 1915 issue Belgian Congo stamps were confiscated by the Germans. Most were returned when hostilities had concluded. The stamps were demonetized and overprinted with new denominations for the centimes values and with “1921” added on the francs values (Scott #64-73). These are known as the “Recovery” or “Recuperation” issue. Since the order to overprint said “all stocks”, some stamps remaining of pre-1915 issues were also overprinted. As supplies of the 1921 issue were depleted, a new overprint was applied in Belgium for the centime values to conform to new postal rates in 1922 (Scott #74-78). Later that year, the “Boma” surcharge was applied in the Congo to four values (Scott #80-81, #84-85). There were several printings.

The last appearance of the “Mols” originally designed for use by the Congo Free State back in 1894 were released by Belgian Congo in 1923. These were further surcharges made at Elizabethville on 1921 and 1922 stamps that had been previously overprinted: the 30 centime overprint on 10 centime stamp received an additional 25-centime surcharge in two versions (Scott #86-87). These were for the use of the Union Miniere due Haut Katanga, the mining combine.

For more on the region, please see my blog entry about Belgian Congo; my entry on the Belgian Occupation of German East Africa (Scott #N17) also features a stamp of the “Mols” design as the Belgian forces originated in the Congo. I have yet to obtain stamps from the Republic of the Congo (République du Congo, also called Congo-Léopoldville) which was the nation formed when Belgian Congo achieved independence in 1960, This name lasted until 1964 when it changed to Democratic Republic of the Congo (République démocratique du Congo) to distinguish it from the neighboring Republic of the Congo (Congo-Brazzaville) which was the former colony of French Congo (Congo français) and later Middle Congo (Moyen-Congo) before becoming part of the confederation of French Equatorial Africa (Afrique équatoriale française). I do not yet have stamps from the Democratic Republic of the Congo either. This was renamed the Republic of Zaire (République du Zaïre) in 1971 but reverted back to the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1997.

Scott #24 was engraved and printed by Waterlow & Sons Ltd. of London and released in November 1894. The lilac and black 1-franc stamp features a lone native hunter with a spear preparing to throw it at a elephant while another elephant remains in the distance. This is one of my all-time favorite stamp designs and epitomizes the “heart of Africa” to me. The entire “Mols” series is a fascinating area for study; all of the stamps are similarly striking and there are a large number of plate varieties, retouches, re-entries, etc. for both the center plates and the frames. There are also many perforation and overprint varieties, including missing letters, double letters, and inverted overprints. Additionally, the 10-centime and 10-franc inverted centers add some challenge (and great expense!) to completing this series.

2 thoughts on “Congo Free State #24 (1894)”