I am a patriot. A Son of the American Revolution with familial links not only to the battlefields of that initial war with Great Britain but to a pallbearer of George Washington himself. As such, I have a deep and abiding interest in the history of the United States of America and continue to promote it even afar, as an expatriate living in southern Thailand for more than fourteen years. This blog, over the course of two years, has detailed the American experience and her story on numerous occasions and, yet, has only mentioned in passing the origin document itself, that grand Declaration of Independence that cast sought to “dissolve the political bands” with Britain that had become increasingly oppressive and to declare the formation of a new nation based on the truth “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

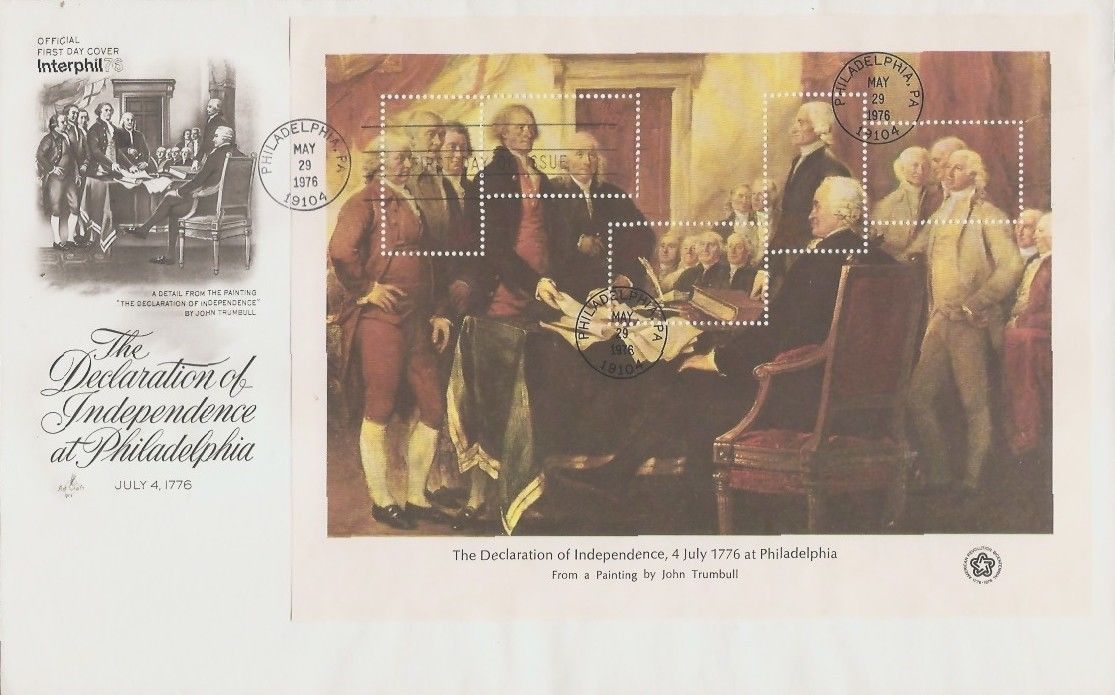

This blog’s first Independence Day entry — 733 articles ago on July 4, 2016 — numbered just 160 words and featured, for a reason I’m still scratching my head over, a stamp from the Republic of San Marino. I did mention, however, that I didn’t have a copy of the 1976 set based on John Trumbell’s painting (Scott #1691-1694). I still don’t own mint copies of the stamps. I do have a copy of the souvenir sheet depicting a the right-side portion of the painting released during that same Bicentennial year (Scott #1687) as featured today. I profiled all of the souvenir sheets in this particular set during the massive stamp issuers article on the United States of America. but always felt that it deserved its own entry. Last year’s July 4th article dispensed with the national day altogether with an entry about the Erie Canal which was celebrating it’s bicentennial in 2017. Today’s article deals exclusively with the background and composition of the Declaration of Independence as well as the document’s legacy.

The United States Declaration of Independence is the statement adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at the Pennsylvania State House (now known as Independence Hall) in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776. The Declaration announced that the thirteen American colonies then at war with the Kingdom of Great Britain would regard themselves as thirteen independent sovereign states no longer under British rule. With the Declaration, these new states took a collective first step toward forming the United States of America. The declaration was signed by representatives from New Hampshire, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia.

The Declaration was passed on July 2 with no opposing votes. A committee of five had drafted it to be ready when Congress voted on independence. John Adams, a leader in pushing for independence, had persuaded the committee to select Thomas Jefferson to compose the original draft of the document, which Congress edited to produce the final version. The Declaration was a formal explanation of why Congress had voted on July 2 to declare independence from Great Britain, more than a year after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War. Adams wrote to his wife Abigail, “The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America” — although Independence Day is actually celebrated on July 4, the date that the wording of the Declaration of Independence was approved.

After ratifying the text on July 4, Congress issued the Declaration of Independence in several forms. It was initially published as the printed Dunlap broadside that was widely distributed and read to the public. The source copy used for this printing has been lost and may have been a copy in Thomas Jefferson’s hand. Jefferson’s original draft is preserved at the Library of Congress, complete with changes made by John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, as well as Jefferson’s notes of changes made by Congress. The best-known version of the Declaration is a signed copy that is displayed at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., and which is popularly regarded as the official document. This engrossed copy was ordered by Congress on July 19 and signed primarily on August 2.

The sources and interpretation of the Declaration have been the subject of much scholarly inquiry. The Declaration justified the independence of the United States by listing colonial grievances against King George III and by asserting certain natural and legal rights, including a right of revolution. Having served its original purpose in announcing independence, references to the text of the Declaration were few in the following years. Abraham Lincoln made it the centerpiece of his policies and his rhetoric, as in the Gettysburg Address of 1863. Since then, it has become a well-known statement on human rights, particularly its second sentence:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

This has been called “one of the best-known sentences in the English language”, containing “the most potent and consequential words in American history”. The passage came to represent a moral standard to which the United States should strive. This view was notably promoted by Lincoln, who considered the Declaration to be the foundation of his political philosophy and argued that it is a statement of principles through which the United States Constitution should be interpreted.

The U.S. Declaration of Independence inspired many similar documents in other countries, the first being the 1789 Declaration of Flanders issued during the Brabant Revolution in the Austrian Netherlands (modern-day Belgium). It also served as the primary model for numerous declarations of independence in Europe and Latin America, as well as Africa (Liberia) and Oceania (New Zealand) during the first half of the 19th century.

Believe me, dear Sir: there is not in the British empire a man who more cordially loves a union with Great Britain than I do. But, by the God that made me, I will cease to exist before I yield to a connection on such terms as the British Parliament propose; and in this, I think I speak the sentiments of America.

— Thomas Jefferson, November 29, 1775

By the time that the Declaration of Independence was adopted in July 1776, the Thirteen Colonies and Great Britain had been at war for more than a year. Relations had been deteriorating between the colonies and the mother country since 1763. Parliament enacted a series of measures to increase revenue from the colonies, such as the Stamp Act of 1765 and the Townshend Acts of 1767. Parliament believed that these acts were a legitimate means of having the colonies pay their fair share of the costs to keep them in the British Empire.

Many colonists, however, had developed a different conception of the empire. The colonies were not directly represented in Parliament, and colonists argued that Parliament had no right to levy taxes upon them. This tax dispute was part of a larger divergence between British and American interpretations of the British Constitution and the extent of Parliament’s authority in the colonies. The orthodox British view, dating from the Glorious Revolution of 1688, was that Parliament was the supreme authority throughout the empire, and so, by definition, anything that Parliament did was constitutional. In the colonies, however, the idea had developed that the British Constitution recognized certain fundamental rights that no government could violate, not even Parliament. After the Townshend Acts, some essayists even began to question whether Parliament had any legitimate jurisdiction in the colonies at all. Anticipating the arrangement of the British Commonwealth, by 1774 American writers such as Samuel Adams, James Wilson, and Thomas Jefferson were arguing that Parliament was the legislature of Great Britain only, and that the colonies, which had their own legislatures, were connected to the rest of the empire only through their allegiance to the Crown.

The issue of Parliament’s authority in the colonies became a crisis after Parliament passed the Coercive Acts (known as the Intolerable Acts in the colonies) in 1774 to punish the Province of Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party of 1773. Many colonists saw the Coercive Acts as a violation of the British Constitution and thus a threat to the liberties of all of British America. In September 1774, the First Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia to coordinate a response. Congress organized a boycott of British goods and petitioned the king for repeal of the acts. These measures were unsuccessful because King George and the ministry of Prime Minister Lord North were determined not to retreat on the question of parliamentary supremacy. As the king wrote to North in November 1774, “blows must decide whether they are to be subject to this country or independent”.

Most colonists still hoped for reconciliation with Great Britain, even after fighting began in the American Revolutionary War at Lexington and Concord in April 1775. The Second Continental Congress convened at the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia in May 1775, and some delegates hoped for eventual independence, but no one yet advocated declaring it. Many colonists no longer believed that Parliament had any sovereignty over them, yet they still professed loyalty to King George, who they hoped would intercede on their behalf. They were disappointed in late 1775, when the king rejected Congress’s second petition, issued a Proclamation of Rebellion, and announced before Parliament on October 26 that he was considering “friendly offers of foreign assistance” to suppress the rebellion. A pro-American minority in Parliament warned that the government was driving the colonists toward independence.

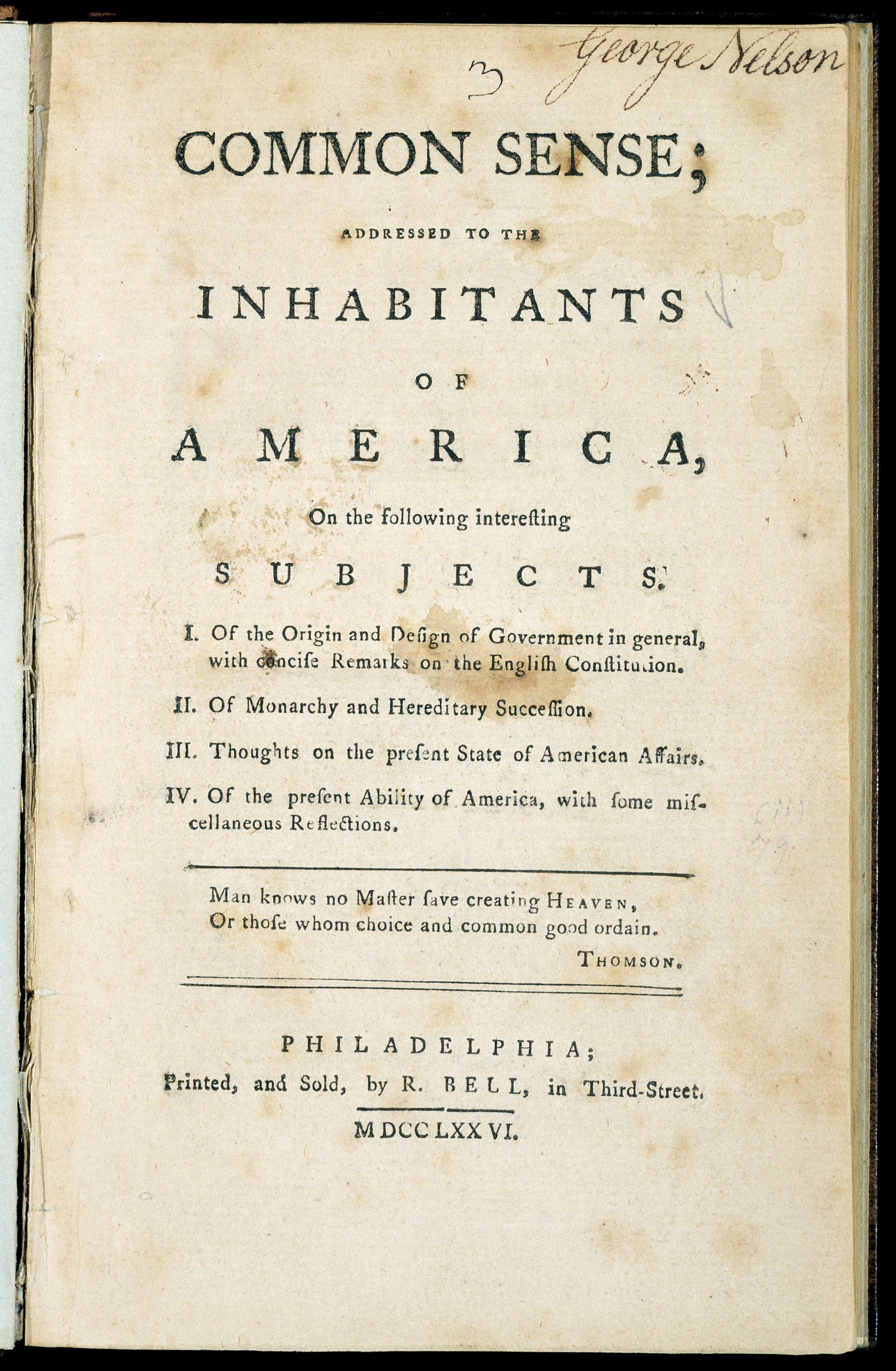

Thomas Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense was published in January 1776, just as it became clear in the colonies that the king was not inclined to act as a conciliator. Paine had only recently arrived in the colonies from England, and he argued in favor of colonial independence, advocating republicanism as an alternative to monarchy and hereditary rule. Common Sense made a persuasive and impassioned case for independence, which had not yet been given serious intellectual consideration in the American colonies. Paine connected independence with Protestant beliefs as a means to present a distinctly American political identity, thereby stimulating public debate on a topic that few had previously dared to openly discuss, and public support for separation from Great Britain steadily increased after its publication.

Some colonists still held out hope for reconciliation, but developments in early 1776 further strengthened public support for independence. In February 1776, colonists learned of Parliament’s passage of the Prohibitory Act, which established a blockade of American ports and declared American ships to be enemy vessels. John Adams, a strong supporter of independence, believed that Parliament had effectively declared American independence before Congress had been able to. Adams labeled the Prohibitory Act the “Act of Independency”, calling it “a compleat Dismemberment of the British Empire”. Support for declaring independence grew even more when it was confirmed that King George had hired German mercenaries to use against his American subjects.

Despite this growing popular support for independence, Congress lacked the clear authority to declare it. Delegates had been elected to Congress by 13 different governments, which included extralegal conventions, ad hoc committees, and elected assemblies, and they were bound by the instructions given to them. Regardless of their personal opinions, delegates could not vote to declare independence unless their instructions permitted such an action. Several colonies, in fact, expressly prohibited their delegates from taking any steps towards separation from Great Britain, while other delegations had instructions that were ambiguous on the issue; consequently, advocates of independence sought to have the Congressional instructions revised. For Congress to declare independence, a majority of delegations would need authorization to vote for it, and at least one colonial government would need to specifically instruct its delegation to propose a declaration of independence in Congress. Between April and July 1776, a “complex political war” was waged to bring this about.

In the campaign to revise Congressional instructions, many Americans formally expressed their support for separation from Great Britain in what were effectively state and local declarations of independence. Historian Pauline Maier identifies more than ninety such declarations that were issued throughout the Thirteen Colonies from April to July 1776. These “declarations” took a variety of forms. Some were formal written instructions for Congressional delegations, such as the Halifax Resolves of April 12, with which North Carolina became the first colony to explicitly authorize its delegates to vote for independence. Others were legislative acts that officially ended British rule in individual colonies, such as the Rhode Island legislature declaring its independence from Great Britain on May 4, the first colony to do so. Many “declarations” were resolutions adopted at town or county meetings that offered support for independence. A few came in the form of jury instructions, such as the statement issued on April 23, 1776, by Chief Justice William Henry Drayton of South Carolina: “the law of the land authorizes me to declare…that George the Third, King of Great Britain…has no authority over us, and we owe no obedience to him.” Most of these declarations are now obscure, having been overshadowed by the declaration approved by Congress on July 2, and signed July 4.

Some colonies held back from endorsing independence. Resistance was centered in the middle colonies of New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. Advocates of independence saw Pennsylvania as the key; if that colony could be converted to the pro-independence cause, it was believed that the others would follow. On May 1, however, opponents of independence retained control of the Pennsylvania Assembly in a special election that had focused on the question of independence. In response, Congress passed a resolution on May 10 which had been promoted by John Adams and Richard Henry Lee, calling on colonies without a “government sufficient to the exigencies of their affairs” to adopt new governments. The resolution passed unanimously, and was even supported by Pennsylvania’s John Dickinson, the leader of the anti-independence faction in Congress, who believed that it did not apply to his colony.

As was the custom, Congress appointed a committee to draft a preamble to explain the purpose of the resolution. John Adams wrote the preamble, which stated that because King George had rejected reconciliation and was hiring foreign mercenaries to use against the colonies, “it is necessary that the exercise of every kind of authority under the said crown should be totally suppressed”. Adams’s preamble was meant to encourage the overthrow of the governments of Pennsylvania and Maryland, which were still under proprietary governance. Congress passed the preamble on May 15 after several days of debate, but four of the middle colonies voted against it, and the Maryland delegation walked out in protest. Adams regarded his May 15 preamble effectively as an American declaration of independence, although a formal declaration would still have to be made.

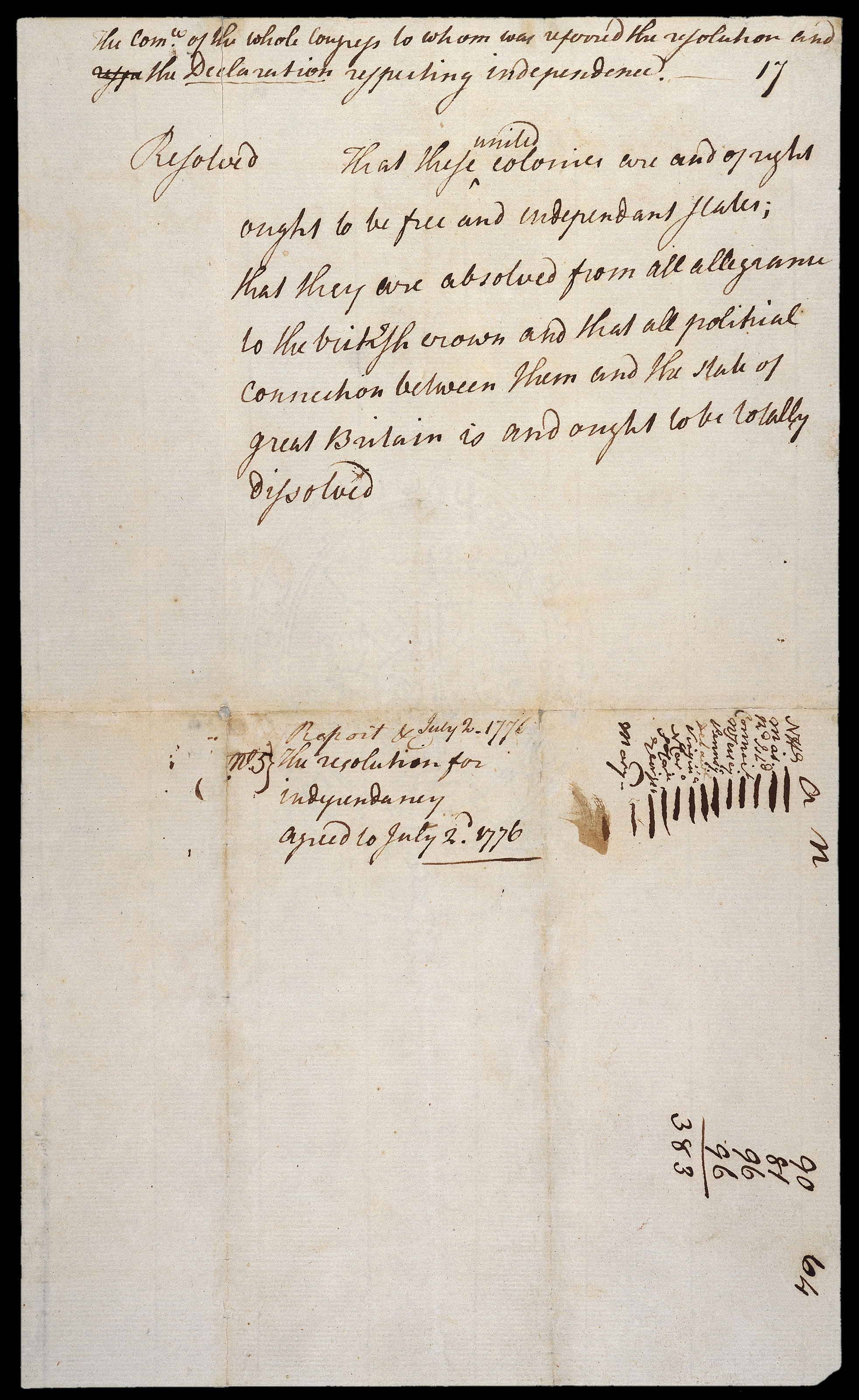

On the same day that Congress passed Adams’s radical preamble, the Virginia Convention set the stage for a formal Congressional declaration of independence. On May 15, the Convention instructed Virginia’s congressional delegation “to propose to that respectable body to declare the United Colonies free and independent States, absolved from all allegiance to, or dependence upon, the Crown or Parliament of Great Britain”. In accordance with those instructions, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia presented a three-part resolution to Congress on June 7. The motion was seconded by John Adams, calling on Congress to declare independence, form foreign alliances, and prepare a plan of colonial confederation. The part of the resolution relating to declaring independence read:

Resolved, that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

Lee’s resolution met with resistance in the ensuing debate. Opponents of the resolution conceded that reconciliation was unlikely with Great Britain, while arguing that declaring independence was premature, and that securing foreign aid should take priority. Advocates of the resolution countered that foreign governments would not intervene in an internal British struggle, and so a formal declaration of independence was needed before foreign aid was possible. All Congress needed to do, they insisted, was to “declare a fact which already exists”. Delegates from Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, Maryland, and New York were still not yet authorized to vote for independence, however, and some of them threatened to leave Congress if the resolution were adopted. Congress, therefore, voted on June 10 to postpone further discussion of Lee’s resolution for three weeks. Until then, Congress decided that a committee should prepare a document announcing and explaining independence in the event that Lee’s resolution was approved when it was brought up again in July.

Support for a Congressional declaration of independence was consolidated in the final weeks of June 1776. On June 14, the Connecticut Assembly instructed its delegates to propose independence and, the following day, the legislatures of New Hampshire and Delaware authorized their delegates to declare independence. In Pennsylvania, political struggles ended with the dissolution of the colonial assembly, and a new Conference of Committees under Thomas McKean authorized Pennsylvania’s delegates to declare independence on June 18. The Provincial Congress of New Jersey had been governing the province since January 1776; they resolved on June 15 that Royal Governor William Franklin was “an enemy to the liberties of this country” and had him arrested. On June 21, they chose new delegates to Congress and empowered them to join in a declaration of independence.

Only Maryland and New York had yet to authorize independence towards the end of June. Previously, Maryland’s delegates had walked out when the Continental Congress adopted Adams’s radical May 15 preamble, and had sent to the Annapolis Convention for instructions. On May 20, the Annapolis Convention rejected Adams’s preamble, instructing its delegates to remain against independence. Samuel Chase went to Maryland and, thanks to local resolutions in favor of independence, was able to get the Annapolis Convention to change its mind on June 28. Only the New York delegates were unable to get revised instructions. When Congress had been considering the resolution of independence on June 8, the New York Provincial Congress told the delegates to wait. But on June 30, the Provincial Congress evacuated New York as British forces approached, and would not convene again until July 10. This meant that New York’s delegates would not be authorized to declare independence until after Congress had made its decision.

Political maneuvering was setting the stage for an official declaration of independence even while a document was being written to explain the decision. On June 11, 1776, Congress appointed a “Committee of Five” to draft a declaration, consisting of John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut. The committee left no minutes, so there is some uncertainty about how the drafting process proceeded; contradictory accounts were written many years later by Jefferson and Adams, too many years to be regarded as entirely reliable — although their accounts are frequently cited.

What is certain is that the committee discussed the general outline which the document should follow and decided that Jefferson would write the first draft. The committee in general, and Jefferson in particular, thought that Adams should write the document, but Adams persuaded the committee to choose Jefferson and promised to consult with him personally. Considering Congress’s busy schedule, Jefferson probably had limited time for writing over the next seventeen days, and likely wrote the draft quickly. He then consulted the others and made some changes, and then produced another copy incorporating these alterations. The committee presented this copy to the Congress on June 28, 1776. The title of the document was “A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress assembled.”

Congress ordered that the draft “lie on the table”. For two days, Congress methodically edited Jefferson’s primary document, shortening it by a fourth, removing unnecessary wording, and improving sentence structure. They removed Jefferson’s assertion that Britain had forced slavery on the colonies in order to moderate the document and appease persons in Britain who supported the Revolution. Jefferson wrote that Congress had “mangled” his draft version, but the Declaration that was finally produced was “the majestic document that inspired both contemporaries and posterity,” in the words of his biographer John Ferling.

Congress tabled the draft of the declaration on Monday, July 1, and resolved itself into a committee of the whole, with Benjamin Harrison of Virginia presiding, and they resumed debate on Lee’s resolution of independence. John Dickinson made one last effort to delay the decision, arguing that Congress should not declare independence without first securing a foreign alliance and finalizing the Articles of Confederation. John Adams gave a speech in reply to Dickinson, restating the case for an immediate declaration.

A vote was taken after a long day of speeches, each colony casting a single vote, as always. The delegation for each colony numbered from two to seven members, and each delegation voted amongst themselves to determine the colony’s vote. Pennsylvania and South Carolina voted against declaring independence. The New York delegation abstained, lacking permission to vote for independence. Delaware cast no vote because the delegation was split between Thomas McKean (who voted yes) and George Read (who voted no). The remaining nine delegations voted in favor of independence, which meant that the resolution had been approved by the committee of the whole. The next step was for the resolution to be voted upon by Congress itself. Edward Rutledge of South Carolina was opposed to Lee’s resolution but desirous of unanimity, and he moved that the vote be postponed until the following day.

On July 2, South Carolina reversed its position and voted for independence. In the Pennsylvania delegation, Dickinson and Robert Morris abstained, allowing the delegation to vote three-to-two in favor of independence. The tie in the Delaware delegation was broken by the timely arrival of Caesar Rodney, who voted for independence. The New York delegation abstained once again since they were still not authorized to vote for independence, although they were allowed to do so a week later by the New York Provincial Congress. The resolution of independence had been adopted with twelve affirmative votes and one abstention. With this, the colonies had officially severed political ties with Great Britain.

John Adams predicted in a famous letter, written to his wife on the following day, that July 2 would become a great American holiday. He thought that the vote for independence would be commemorated; he did not foresee that Americans — including himself — would instead celebrate Independence Day on the date when the announcement of that act was finalized.

“I am apt to believe that [Independence Day] will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.”

After voting in favor of the resolution of independence, Congress turned its attention to the committee’s draft of the declaration. Over several days of debate, they made a few changes in wording and deleted nearly a fourth of the text and, on July 4, 1776, the wording of the Declaration of Independence was approved and sent to the printer for publication.

There is a distinct change in wording from this original broadside printing of the Declaration and the final official engrossed copy. The word “unanimous” was inserted as a result of a Congressional resolution passed on July 19, 1776:

Resolved, That the Declaration passed on the 4th, be fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile of “The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America,” and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress.

Historian George Billias says:

Independence amounted to a new status of interdependence: the United States was now a sovereign nation entitled to the privileges and responsibilities that came with that status. America thus became a member of the international community, which meant becoming a maker of treaties and alliances, a military ally in diplomacy, and a partner in foreign trade on a more equal basis.

The Declaration became official when Congress voted for it on July 4; signatures of the delegates were not needed to make it official. The handwritten copy of the Declaration of Independence that was signed by Congress is dated July 4, 1776. The signatures of fifty-six delegates are affixed; however, the exact date when each person signed it has long been the subject of debate. Jefferson, Franklin, and Adams all wrote that the Declaration had been signed by Congress on July 4. In 1796, signer Thomas McKean disputed that the Declaration had been signed on July 4, pointing out that some signers were not then present, including several who were not even elected to Congress until after that date.

The Declaration was transposed on paper, adopted by the Continental Congress, and signed by John Hancock, President of the Congress, on July 4, 1776, according to the 1911 record of events by the U.S. State Department under Secretary Philander C. Knox. On August 2, 1776, a parchment paper copy of the Declaration was signed by 56 persons. Many of these signers were not present when the original Declaration was adopted on July 4. Signer Matthew Thornton from New Hampshire was seated in the Continental Congress in November; he asked for and received the privilege of adding his signature at that time, and signed on November 4, 1776.

Historians have generally accepted McKean’s version of events, arguing that the famous signed version of the Declaration was created after July 19, and was not signed by Congress until August 2, 1776. In 1986, legal historian Wilfred Ritz argued that historians had misunderstood the primary documents and given too much credence to McKean, who had not been present in Congress on July 4. According to Ritz, about thirty-four delegates signed the Declaration on July 4, and the others signed on or after August 2. Historians who reject a July 4 signing maintain that most delegates signed on August 2, and that those eventual signers who were not present added their names later.

Two future U.S. presidents were among the signatories: Thomas Jefferson and John Adams. The most famous signature on the engrossed copy is that of John Hancock, who presumably signed first as President of Congress. Hancock’s large, flamboyant signature became iconic, and the term John Hancock emerged in the United States as an informal synonym for “signature”. A commonly circulated but apocryphal account claims that, after Hancock signed, the delegate from Massachusetts commented, “The British ministry can read that name without spectacles.” Another apocryphal report indicates that Hancock proudly declared, “There! I guess King George will be able to read that!”

Various legends emerged years later about the signing of the Declaration, when the document had become an important national symbol. In one famous story, John Hancock supposedly said that Congress, having signed the Declaration, must now “all hang together”, and Benjamin Franklin replied: “Yes, we must indeed all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately.” The quotation did not appear in print until more than fifty years after Franklin’s death.

The Syng inkstand used at the signing was also used at the signing of the United States Constitution in 1787.

After Congress approved the final wording of the Declaration on July 4, a handwritten copy was sent a few blocks away to the printing shop of John Dunlap. Through the night, Dunlap printed about 200 broadsides for distribution. Before long, it was being read to audiences and reprinted in newspapers throughout the 13 states. The first formal public readings of the document took place on July 8, in Philadelphia (by John Nixon in the yard of Independence Hall), Trenton, New Jersey, and Easton, Pennsylvania; the first newspaper to publish it was the Pennsylvania Evening Post on July 6. A German translation of the Declaration was published in Philadelphia by July 9.

President of Congress John Hancock sent a broadside to General George Washington, instructing him to have it proclaimed “at the Head of the Army in the way you shall think it most proper”. Washington had the Declaration read to his troops in New York City on July 9, with thousands of British troops on ships in the harbor. Washington and Congress hoped that the Declaration would inspire the soldiers, and encourage others to join the army. After hearing the Declaration, crowds in many cities tore down and destroyed signs or statues representing royal authority. An equestrian statue of King George in New York City was pulled down and the lead used to make musket balls.

British officials in North America sent copies of the Declaration to Great Britain. It was published in British newspapers beginning in mid-August, it had reached Florence and Warsaw by mid-September, and a German translation appeared in Switzerland by October. The first copy of the Declaration sent to France got lost, and the second copy arrived only in November 1776. It reached Portuguese America by Brazilian medical student “Vendek” José Joaquim Maia e Barbalho, who had met with Thomas Jefferson in Nîmes.

The Spanish-American authorities banned the circulation of the Declaration, but it was widely transmitted and translated: by Venezuelan Manuel García de Sena, by Colombian Miguel de Pombo, by Ecuadorian Vicente Rocafuerte, and by New Englanders Richard Cleveland and William Shaler, who distributed the Declaration and the United States Constitution among Creoles in Chile and Indians in Mexico in 1821.

The government of Great Britain led by Lord North did not give an official answer to the Declaration, but instead secretly commissioned pamphleteer John Lind to publish a response entitled Answer to the Declaration of the American Congress. British Tories denounced the signers of the Declaration for not applying the same principles of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” to African Americans. Thomas Hutchinson, the former royal governor of Massachusetts, also published a rebuttal. These pamphlets challenged various aspects of the Declaration. Hutchinson argued that the American Revolution was the work of a few conspirators who wanted independence from the outset, and who had finally achieved it by inducing otherwise loyal colonists to rebel. Lind’s pamphlet had an anonymous attack on the concept of natural rights written by Jeremy Bentham, an argument that he repeated during the French Revolution. Both pamphlets asked how the American slaveholders in Congress could proclaim that “all men are created equal” without freeing their own slaves.

William Whipple, a signer of the Declaration of Independence who had fought in the war, freed his slave Prince Whipple because of revolutionary ideals. In the postwar decades, other slaveholders also freed their slaves; from 1790 to 1810, the percentage of free blacks in the Upper South increased to 8.3 percent from less than one percent of the black population. All Northern states abolished slavery by 1804.

The official copy of the Declaration of Independence was the one printed on July 4, 1776, under Jefferson’s supervision. It was sent to the states and to the Army and was widely reprinted in newspapers. The slightly different engrossed or parchment copy was made later for members to sign. It was probably engrossed (that is, carefully handwritten) by clerk Timothy Matlack. The opening lines differ between the two versions.

A facsimile made in 1823 has become the basis of most modern reproductions rather than the original because of poor conservation of the engrossed copy through the 19th century. In 1921, custody of the engrossed copy of the Declaration was transferred from the State Department to the Library of Congress, along with the United States Constitution. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the documents were moved for safekeeping to the United States Bullion Depository at Fort Knox in Kentucky, where they were kept until 1944. In 1952, the engrossed Declaration was transferred to the National Archives and is now on permanent display at the National Archives in the “Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom”.

The document signed by Congress and enshrined in the National Archives is usually regarded as the Declaration of Independence, but historian Julian P. Boyd argued that the Declaration, like Magna Carta, is not a single document. Boyd considered the printed broadsides ordered by Congress to be official texts, as well. The Declaration was first published as a broadside that was printed the night of July 4 by John Dunlap of Philadelphia. Dunlap printed about 200 broadsides, of which 26 are known to survive. The 26th copy was discovered in The National Archives in England in 2009.

In 1777, Congress commissioned Mary Katherine Goddard to print a new broadside that listed the signers of the Declaration, unlike the Dunlap broadside. Nine copies of the Goddard broadside are known to still exist. A variety of broadsides printed by the states are also extant.

Several early handwritten copies and drafts of the Declaration have also been preserved. Jefferson kept a four-page draft that late in life he called the “original Rough draught”. It is not known how many drafts Jefferson wrote prior to this one, and how much of the text was contributed by other committee members. In 1947, Boyd discovered a fragment of an earlier draft in Jefferson’s handwriting. Jefferson and Adams sent copies of the rough draft to friends, with slight variations.

During the writing process, Jefferson showed the rough draft to Adams and Franklin, and perhaps to other members of the drafting committee,[132] who made a few more changes. Franklin, for example, may have been responsible for changing Jefferson’s original phrase “We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable” to “We hold these truths to be self-evident”. Jefferson incorporated these changes into a copy that was submitted to Congress in the name of the committee. The copy that was submitted to Congress on June 28 has been lost and was perhaps destroyed in the printing process, or destroyed during the debates in accordance with Congress’s secrecy rule.

On April 21, 2017, it was announced that a second engrossed copy had been discovered in an archive in Sussex, England. Named by its finders the “Sussex Declaration”, it differs from the National Archives copy (which the finders refer to as the “Matlack Declaration”) in that the signatures on it are not grouped by States. How it came to be in England is not yet known, but the finders believe that the randomness of the signatures points to an origin with signatory James Wilson, who had argued strongly that the Declaration was made not by the States but by the whole people.

The Declaration was given little attention in the years immediately following the American Revolution, having served its original purpose in announcing the independence of the United States. Early celebrations of Independence Day largely ignored the Declaration, as did early histories of the Revolution. The act of declaring independence was considered important, whereas the text announcing that act attracted little attention. The Declaration was rarely mentioned during the debates about the United States Constitution, and its language was not incorporated into that document. George Mason’s draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights was more influential, and its language was echoed in state constitutions and state bills of rights more often than Jefferson’s words. “In none of these documents”, wrote Pauline Maier, “is there any evidence whatsoever that the Declaration of Independence lived in men’s minds as a classic statement of American political principles.”

Many leaders of the French Revolution admired the Declaration of Independence but were also interested in the new American state constitutions. The inspiration and content of the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen (1789) emerged largely from the ideals of the American Revolution. Its key drafts were prepared by Lafayette, working closely in Paris with his friend Thomas Jefferson. It also borrowed language from George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights. The declaration also influenced the Russian Empire. The document had a particular impact on the Decembrist revolt and other Russian thinkers.

According to historian David Armitage, the Declaration of Independence did prove to be internationally influential, but not as a statement of human rights. Armitage argued that the Declaration was the first in a new genre of declarations of independence that announced the creation of new states.

Other French leaders were directly influenced by the text of the Declaration of Independence itself. The Manifesto of the Province of Flanders (1790) was the first foreign derivation of the Declaration; others include the Venezuelan Declaration of Independence (1811), the Liberian Declaration of Independence (1847), the declarations of secession by the Confederate States of America (1860–61), and the Vietnamese Proclamation of Independence (1945). These declarations echoed the United States Declaration of Independence in announcing the independence of a new state, without necessarily endorsing the political philosophy of the original.

Other countries have used the Declaration as inspiration or have directly copied sections from it. These include the Haitian declaration of January 1, 1804, during the Haitian Revolution, the United Provinces of New Granada in 1811, the Argentine Declaration of Independence in 1816, the Chilean Declaration of Independence in 1818, Costa Rica in 1821, El Salvador in 1821, Guatemala in 1821, Honduras in (1821), Mexico in 1821, Nicaragua in 1821, Peru in 1821, Bolivian War of Independence in 1825, Uruguay in 1825, Ecuador in 1830, Colombia in 1831, Paraguay in 1842, Dominican Republic in 1844, Texas Declaration of Independence in March 1836, California Republic in November 1836, Hungarian Declaration of Independence in 1849, Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand in 1835, and the Czechoslovak declaration of independence from 1918 drafted in Washington D.C. with Gutzon Borglum among the drafters. The Rhodesian declaration of independence, ratified in November 1965, is based on the American one as well; however, it omits the phrases “all men are created equal” and “the consent of the governed”. The South Carolina declaration of secession from December 1860 also mentions the U.S. Declaration of Independence, though it, like the Rhodesian one, omits references to “all men are created equal” and “consent of the governed”.

![Federalist poster about 1800. Washington (in heaven) tells partisans to keep the pillars of Federalism, Republicanism and Democracy. Another source: A 1795 [¿? Washington died in 1799] cartoon depicting Washington warning party men to let all three pillars of Federalism, Republicanism, and Democracy stand to hold up Peace and Plenty, Liberty and Independence. At the left a Democrat says](https://farm2.staticflickr.com/1808/42282062305_413e3fda7b_o.jpg)

Interest in the Declaration was revived in the 1790s with the emergence of the United States’s first political parties. Throughout the 1780s, few Americans knew or cared who wrote the Declaration. In the next decade, Jeffersonian Republicans sought political advantage over their rival Federalists by promoting both the importance of the Declaration and Jefferson as its author. Federalists responded by casting doubt on Jefferson’s authorship or originality, and by emphasizing that independence was declared by the whole Congress, with Jefferson as just one member of the drafting committee. Federalists insisted that Congress’s act of declaring independence, in which Federalist John Adams had played a major role, was more important than the document announcing it. This view faded away, like the Federalist Party itself, and, before long, the act of declaring independence became synonymous with the document.

A less partisan appreciation for the Declaration emerged in the years following the War of 1812, thanks to a growing American nationalism and a renewed interest in the history of the Revolution. In 1817, Congress commissioned John Trumbull’s famous painting of the signers, which was exhibited to large crowds before being installed in the Capitol. The earliest commemorative printings of the Declaration also appeared at this time, offering many Americans their first view of the signed document. Collective biographies of the signers were first published in the 1820s, giving birth to what Garry Wills called the “cult of the signers”. In the years that followed, many stories about the writing and signing of the document were published for the first time.

When interest in the Declaration was revived, the sections that were most important in 1776 were no longer relevant: the announcement of the independence of the United States and the grievances against King George. But the second paragraph was applicable long after the war had ended, with its talk of self-evident truths and unalienable rights. The Constitution and the Bill of Rights lacked sweeping statements about rights and equality, and advocates of groups with grievances turned to the Declaration for support. Starting in the 1820s, variations of the Declaration were issued to proclaim the rights of workers, farmers, women, and others. In 1848, for example, the Seneca Falls Convention of women’s rights advocates declared that “all men and women are created equal”.

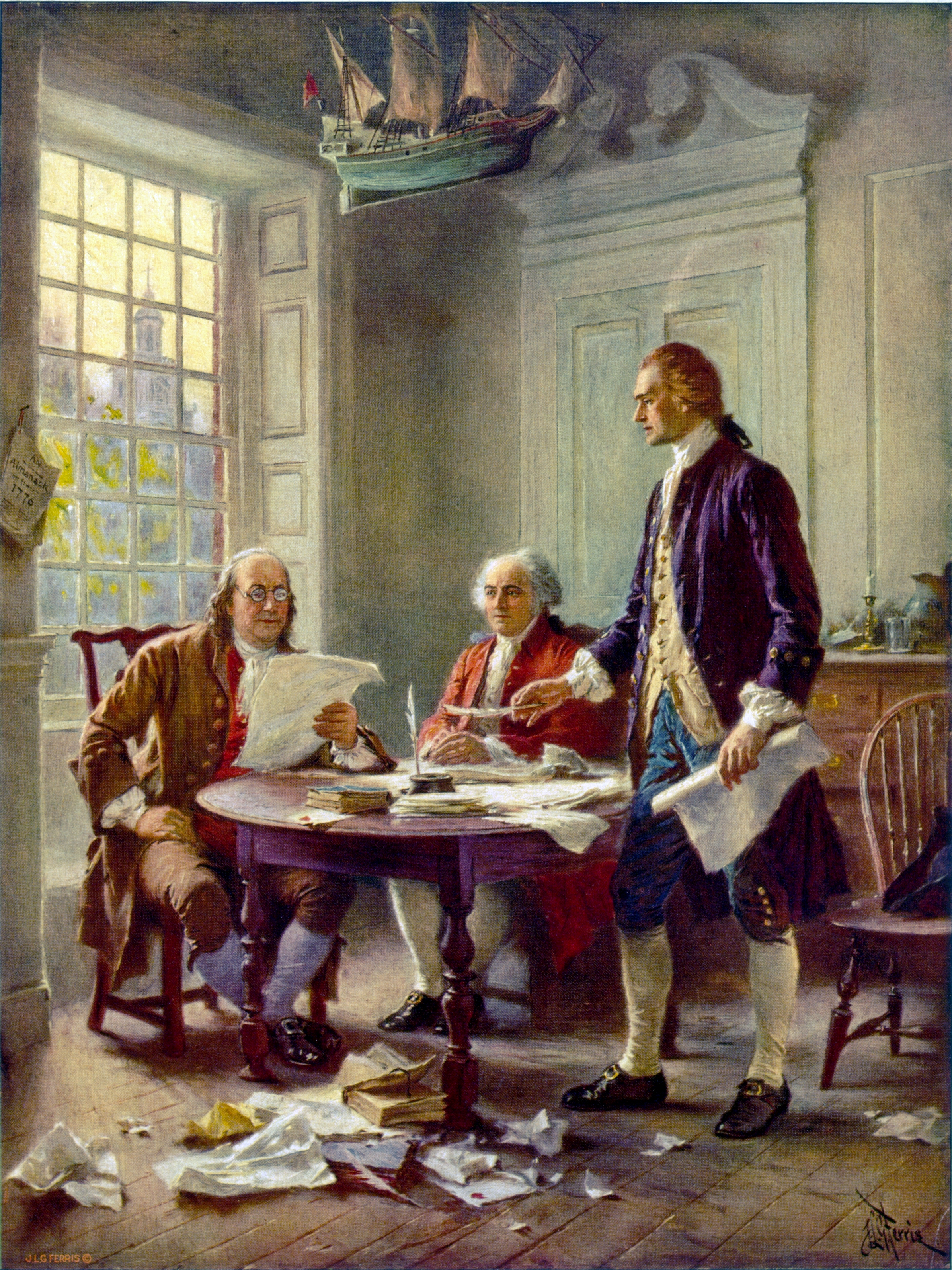

John Trumbull’s painting Declaration of Independence has played a significant role in popular conceptions of the Declaration of Independence. The painting is 12-by-18-foot (3.7 by 5.5 m) in size and was commissioned by the United States Congress in 1817; it has hung in the United States Capitol Rotunda since 1826. It is sometimes described as the signing of the Declaration of Independence, but it actually shows the Committee of Five presenting their draft of the Declaration to the Second Continental Congress on June 28, 1776, and not the signing of the document, which took place later.

Trumbull painted the figures from life whenever possible, but some had died and images could not be located; hence, the painting does not include all the signers of the Declaration. One figure had participated in the drafting but did not sign the final document; another refused to sign. In fact, the membership of the Second Continental Congress changed as time passed, and the figures in the painting were never in the same room at the same time. It is, however, an accurate depiction of the room in Independence Hall, the centerpiece of the Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Trumbull’s painting has been depicted multiple times on U.S. currency and postage stamps. Its first use was on the reverse side of the $100 National Bank Note issued in 1863. A few years later, the steel engraving used in printing the bank notes was used to produce a 24-cent stamp, issued as part of the 1869 Pictorial Issue. An engraving of the signing scene has been featured on the reverse side of the United States two-dollar bill since 1976.

Independence Day, also referred to as the Fourth of July or July Fourth, is a federal holiday in the United States commemorating the adoption of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. Coincidentally, both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, the only signers of the Declaration of Independence later to serve as Presidents of the United States, died on the same day: July 4, 1826, which was the 50th anniversary of the Declaration. Although not a signer of the Declaration of Independence, James Monroe, another Founding Father who was elected as President, also died on July 4, 1831. He was the third President who died on the anniversary of independence. Calvin Coolidge, the 30th President, was born on July 4, 1872; so far he is the only U.S. President to have been born on Independence Day.

Independence Day is commonly associated with fireworks, parades, barbecues, carnivals, fairs, picnics, concerts, baseball games, family reunions, and political speeches and ceremonies, in addition to various other public and private events celebrating the history, government, and traditions of the United States. Independence Day is the National Day of the United States.

In 1777, thirteen gunshots were fired in salute, once at morning and once again as evening fell, on July 4 in Bristol, Rhode Island. Philadelphia celebrated the first anniversary in a manner a modern American would find familiar: an official dinner for the Continental Congress, toasts, 13-gun salutes, speeches, prayers, music, parades, troop reviews, and fireworks. Ships in port were decked with red, white, and blue bunting.

In 1778, from his headquarters at Ross Hall, near New Brunswick, New Jersey, General George Washington marked July 4 with a double ration of rum for his soldiers and an artillery salute (feu de joie). Across the Atlantic Ocean, ambassadors John Adams and Benjamin Franklin held a dinner for their fellow Americans in Paris, France.

In 1779, July 4 fell on a Sunday. The holiday was celebrated on Monday, July 5.

In 1781, the Massachusetts General Court became the first state legislature to recognize July 4 as a state celebration.

In 1783, Moravians in Salem, North Carolina, held a celebration of July 4 with a challenging music program assembled by Johann Friedrich Peter. This work was titled The Psalm of Joy. This is recognized as the first recorded celebration and is still celebrated there today.

In 1870, the U.S. Congress made Independence Day an unpaid holiday for federal employees. In 1938, Congress changed Independence Day to a paid federal holiday, so all non-essential federal institutions (such as the postal service and federal courts) are closed on that day. Today, the holiday is marked by patriotic displays. Similar to other summer-themed events, Independence Day celebrations often take place outdoors. Many politicians make it a point on this day to appear at a public event to praise the nation’s heritage, laws, history, society, and people.

Families often celebrate Independence Day by hosting or attending a picnic or barbecue; many take advantage of the day off and, in some years, a long weekend to gather with relatives or friends. Decorations (for example, streamers, balloons, and clothing) are generally colored red, white, and blue, the colors of the American flag. Parades are often held in the morning, before family get-togethers, while fireworks displays occur in the evening after dark at such places as parks, fairgrounds, or town squares.

The night before the Fourth was once the focal point of celebrations, marked by raucous gatherings often incorporating bonfires as their centerpiece. In New England, towns competed to build towering pyramids, assembled from barrels and casks. They were lit at nightfall to usher in the celebration. The highest were in Salem, Massachusetts, with pyramids composed of as many as forty tiers of barrels. These made the tallest bonfires ever recorded. The custom flourished in the 19th and 20th centuries and is still practiced in some New England towns.

Independence Day fireworks are often accompanied by patriotic songs such as the national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner”; “God Bless America”; “America the Beautiful”; “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee”; “This Land Is Your Land”; “Stars and Stripes Forever”; and, regionally, “Yankee Doodle” in northeastern states and “Dixie” in southern states. Some of the lyrics recall images of the Revolutionary War or the War of 1812.

Firework shows are held in many states, and many fireworks are sold for personal use or as an alternative to a public show. Safety concerns have led some states to ban fireworks or limit the sizes and types allowed. In addition, local and regional weather conditions may dictate whether the sale or use of fireworks in an area will be allowed. Some local or regional firework sales are limited or prohibited because of dry weather or other specific concerns. On these occasions the public may be prohibited from purchasing or discharging fireworks, but professional displays (such as those at sports events) may still take place, if certain safety precautions have been taken.

A salute of one gun for each state in the United States, called a “salute to the union,” is fired on Independence Day at noon by any capable military base.

In 2009, New York City had the largest fireworks display in the country, with more than 22 tons of pyrotechnics exploded. It generally holds displays in the East River. Other major displays are in Chicago on Lake Michigan; in San Diego over Mission Bay; in Boston on the Charles River; in St. Louis on the Mississippi River; in San Francisco over the San Francisco Bay; and on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

During the annual Windsor-Detroit International Freedom Festival, Detroit, Michigan hosts one of the world’s largest fireworks displays, over the Detroit River, to celebrate Independence Day in conjunction with Windsor, Ontario’s celebration of Canada Day.

The first week of July is typically one of the busiest United States travel periods of the year, as many people use what is often a three-day holiday weekend for extended vacation trips.

Held since 1785, the Bristol Fourth of July Parade in Bristol, Rhode Island, is the oldest continuous Independence Day celebration in the United States.

Since 1868, Seward, Nebraska, has held a celebration on the same town square. In 1979, Seward was designated “America’s Official Fourth of July City-Small Town USA” by resolution of Congress. Seward has also been proclaimed “Nebraska’s Official Fourth of July City” by Governor James Exon in proclamation. Seward is a town of 6,000 but swells to 40,000+ during the July 4 celebrations.

h

The Boston Pops Orchestra has hosted a music and fireworks show over the Charles River Esplanade called the “Boston Pops Fireworks Spectacular” annually since 1973. The event was broadcast nationally from 1991 until 2002 on A&E, and since 2002 by CBS and its Boston station WBZ-TV. WBZ/1030 and WBZ-TV broadcast the entire event locally, and from 2002 through 2012, CBS broadcast the final hour of the concert nationally in primetime. The national broadcast was put on hiatus beginning in 2013, which Pops executive producer David G. Mugar believed was the result of decreasing viewership caused by NBC’s encore presentation of the Macy’s fireworks. The national broadcast was revived for 2016, and expanded to two hours. In 2017, Bloomberg Television took over coverage duty, with WHDH carrying local coverage beginning in 2018.

On the Capitol lawn in Washington, D.C., A Capitol Fourth, a free concert broadcast live by PBS, NPR and the American Forces Network, precedes the fireworks and attracts over half a million people annually.

The Philippines celebrates July 4 as its Republic Day to commemorate that day in 1946 when it ceased to be a U.S. territory and the United States officially recognized Philippine Independence.[31] July 4 was intentionally chosen by the United States because it corresponds to its Independence Day, and this day was observed in the Philippines as Independence Day until 1962. In 1964, the name of the July 4 holiday was changed to Republic Day. Since 1912, the Rebild Society, a Danish-American friendship organization, has held a July 4 weekend festival that serves as a homecoming for Danish-Americans in the Rebild Hills of Denmark. Rebild National Park in Denmark is said to hold the largest July 4 celebrations outside of the United States.

The celebrations of America’s 200th birthday took place throughout the entire year of 1976 and in every corner of the country. At the July 4, 1976, celebrations in Philadelphia, President Gerald Ford remarked, “This union of corrected wrongs and expanded rights has brought the blessings of liberty to 215 million Americans, but the struggle for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness is never truly won. Each generation of Americans, indeed of all humanity, must strive to achieve these aspirations anew. Liberty is a living flame to be fed, not dead ashes to be revered, even in a bicentennial year.”

According to Alexander T. Haimann of the National Postal Museum, “The postage stamps of the United States issued in the years before the Bicentennial and continuing to the present day feature the people and events that symbolize the struggles and achievements of maintaining liberty and equality for every American.”

The official events for the American Bicentennial celebrations began on April 1, 1975, when the American Freedom Train departed Delaware to begin a 21-month, 25,338-mile tour of the 48 contiguous states. For more than a year, a wave of patriotism swept the nation as elaborate firework displays lit up skies across the U.S., an international fleet of tall-mast sailing ships gathered in New York City and Boston, and Queen Elizabeth II made a state visit. The celebration culminated on July 4, 1976, with the 200th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence.

The United States Postal Service issued 113 commemorative stamps over a six-year period in honor of the Bicentennial, beginning with the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission Emblem stamp (Scott #1432). As a group, the Bicentennial Series chronicles one of our nation’s most important chapters, and remembers the events and patriots who made the United States a world model for liberty.

The commemorative stamps released in 1976 for the Bicentennial began with the ‘Spirit of ’76’ issue featuring Archibald Willard’s painting of the Revolutionary War drummer boy. It also issued commemorative stamps honoring Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and Marquis de Lafayette.

On May 29, 1976, the Postal Service issued four souvenir sheets to commemorate INTERPHIL ‘76 — the Seventh International Philatelic Exhibition — in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Scott #1686-1689). There were four denominations: 13 cents, 18 cents, 24 cents, and 31 cents. Each of the souvenir sheets included five stamps as a part of the design. The stamps were perforated and could be detached and used for postage. Each pane depicts a painting of an event during the Revolutionary War. The paintings include “Surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown” by John Trumbull, “Declaration of Independence” by John Trumbull, “Washington Crossing the Delaware” by Emmanuel Leutze and Eastman Johnson, and “Washington Reviewing Army at Valley Forge” by William T. Trego. The stamps were designed by Vincent E. Hoffman.

The 18-cent stamps in Scott #1687 met the surface letter-mail rate for the first ounce to countries other than Canada and Mexico. The souvenir sheet containing these stamps portrays John Trumbull’s “Declaration of Independence” — a 12-by-18-foot (3.7 by 5.5 m) oil-on-canvas painting hanging in the United States Capitol rotunda that depicts the presentation of the draft of the Declaration of Independence to Congress. It was based on a much smaller version of the same scene, presently held by the Yale University Art Gallery.

The painting shows 42 of the 56 signers of the Declaration; Trumbull originally intended to include all 56 signers but was unable to obtain likenesses for all of them. He also depicted several participants in the debate who did not sign the document, including John Dickinson, who declined to sign. Trumbull also had no portrait of Benjamin Harrison V to work with, but his son Benjamin Harrison VI was said to resemble his father, so Trumbull painted him instead. The Declaration was debated and signed over a period of time when membership in Congress changed, so the men in the painting had actually never all been in the same room at the same time.

Thomas Jefferson seems to be stepping on John Adams’ foot in the painting, which many thought was supposed to symbolize their relationship as political enemies. However, upon closer examination of the painting, it can be seen that their feet are merely close together. This part of the image was correctly depicted on the two-dollar bill version.

Transcription of the Declaration of Independence, from the United States National Archives:

In Congress, July 4, 1776.

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.–That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, –That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.–Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers.

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance.

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies:

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our Brittish brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

Georgia

Button Gwinnett

Lyman Hall

George Walton

North Carolina

William Hooper

Joseph Hewes

John Penn

South Carolina

Edward Rutledge

Thomas Heyward, Jr.

Thomas Lynch, Jr.

Arthur Middleton

Massachusetts

John Hancock

Maryland

Samuel Chase

William Paca

Thomas Stone

Charles Carroll of Carrollton

Virginia

George Wythe

Richard Henry Lee

Thomas Jefferson

Benjamin Harrison

Thomas Nelson, Jr.

Francis Lightfoot Lee

Carter Braxton

Pennsylvania

Robert Morris

Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Franklin

John Morton

George Clymer

James Smith

George Taylor

James Wilson

George Ross

Delaware

Caesar Rodney

George Read

Thomas McKean

New York

William Floyd

Philip Livingston

Francis Lewis

Lewis Morris

New Jersey

Richard Stockton

John Witherspoon

Francis Hopkinson

John Hart

Abraham Clark

New Hampshire

Josiah Bartlett

William Whipple

Massachusetts

Samuel Adams

John Adams

Robert Treat Paine

Elbridge Gerry

Rhode Island

Stephen Hopkins

William Ellery

Connecticut

Roger Sherman

Samuel Huntington

William Williams

Oliver Wolcott

New Hampshire

Matthew Thornton