On February 20, 1792, United States President George Washington signed the Postal Service Act into law. This was a piece of federal legislation that established the United States Post Office Department (1792-1971), the predecessor of the United States Postal Service. It was headed by the Postmaster General. Postmaster General John McLean, in office from 1823 to 1829, was the first to call it the Post Office Department rather than just the “Post Office.” The organization received a boost in prestige when President Andrew Jackson invited his Postmaster General, William T. Barry, to sit as a member of the Cabinet in 1829. The Post Office Act of 1872 (17 Stat. 283) elevated the Post Office Department to Cabinet status. During the American Civil War (1861–1865), postal services in the Confederate States of America were provided by the Confederate States of America Post-office Department, headed by Postmaster General John Henninger Reagan. The Postal Reorganization Act was signed by President Richard Nixon on August 12, 1970. It replaced the cabinet-level Post Office Department with the independent United States Postal Service on July 1, 1971. The regulatory role of the postal services was then transferred to the Postal Regulatory Commission.

In the early years of the North American colonies, many attempts were made to initiate a postal service. These early attempts were of small scale and usually involved a colony, Massachusetts Bay Colony for example, setting up a location in Boston where one could post a letter back home to England. Other attempts focused on a dedicated postal service between two of the larger colonies, such as Massachusetts and Virginia, but the available services remained limited in scope and disjointed for many years. For example, informal independently-run postal routes operated in Boston as early as 1639, with a Boston to New York City service starting in 1672.

A central postal organization came to the colonies in 1691, when Thomas Neale received a 21-year grant from the British Crown for a North American Postal Service. On February 17, 1691, a grant of letters patent from the joint sovereigns, William and Mary, empowered him:

“to erect, settle, and establish within the chief parts of their majesties’ colonies and plantations in America, an office or offices for receiving and dispatching letters and pacquets, and to receive, send, and deliver the same under such rates and sums of money as the planters shall agree to give, and to hold and enjoy the same for the term of twenty-one years.”

The patent included the exclusive right to establish and collect a formal postal tax on official documents of all kinds. The tax was repealed a year later. Neale appointed Andrew Hamilton, Governor of New Jersey, as his deputy postmaster. The first postal service in America commenced in February 1692. Rates of postage were fixed and authorized, and measures were taken to establish a post office in each town in Virginia. Massachusetts and the other colonies soon passed postal laws, and a very imperfect post office system was established. Neale’s patent expired in 1710, when Parliament extended the English postal system to the colonies. The chief office was established in New York City, where letters were conveyed by regular packets across the Atlantic.

Before the Revolution, there was only a trickle of business or governmental correspondence between the colonies. Most of the mail went back and forth to counting houses and government offices in London. The Revolution made Philadelphia, the seat of the Continental Congress, the information hub of the new nation. News, new laws, political intelligence, and military orders circulated with a new urgency, and a postal system was necessary. Journalists took the lead, securing post office legislation that allowed them to reach their subscribers at very low cost, and to exchange news from newspapers between the thirteen states. Overthrowing the London-oriented imperial postal service in 1774-1775, printers enlisted merchants and the new political leadership, and created new postal system.

In the early 1770s, William Goddard, a Patriot printer frustrated that the royal postal service was unable to reliably deliver his Pennsylvania Chronicle to its readers or deliver critical news for the paper to Goddard, laid out a plan for the “Constitutional Post” before the Continental Congress on October 5, 1774. Congress waited to act on the plan until after the Battle of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. Benjamin Franklin promoted Goddard’s plan and was appointed as the first postmaster general under the Continental Congress beginning on July 26, 1775, nearly one year before the Congress declared independence from the British Crown. Franklin’s son-in-law, Richard Bache, took over the position on November 7, 1776, when Franklin became an American emissary to France.

Franklin had already made a significant contribution to the postal service in the colonies while serving as the postmaster of Philadelphia from 1737 and as joint postmaster general of the colonies from 1753 to 1774. He was dismissed as colonial postmaster general after the publication of private letters of Massachusetts Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson in Massachusetts; Franklin admitted to acquiring the letters (probably from a third party, and not in any sort of official capacity) and sending them to Massachusetts. While postmaster, Franklin streamlined postal delivery with properly surveyed and marked routes from Maine to Florida (the origins of Route 1), instituted overnight postal travel between the critical cities of New York and Philadelphia and created a standardized rate chart based upon weight and distance.

Samuel Osgood held the postmaster general’s position in New York City from 1789, when the U.S. Constitution came into effect, until the government moved to Philadelphia in 1791. Timothy Pickering took over and, about a year later, the Postal Service Act gave his post greater legislative legitimacy and more effective organization. Pickering continued in the position until 1795, when he briefly served as secretary of war, before becoming the third U.S. secretary of state. The Post Office Act of 1792 was based on the Constitutional authority empowering Congress “To establish post offices and post roads”. The law provided for a greatly expanded postal network, and served editors by charging newspapers an extremely low rate. The law guaranteed the sanctity of personal correspondence, and provided the entire country with low-cost access to information on public affairs, while establishing a right to personal privacy.

Because news was considered crucial to an informed electorate, the 1792 law distributed newspapers to subscribers for 1 penny up to 100 miles and 1.5 cents over 100 miles; printers could send their newspapers to other newspaper publishers for free. Postage for letters, by contrast, cost between 6 and 25 cents depending on distance.

The postmaster general’s position was considered a plum patronage post for political allies of the president until the Postal Service was transformed into a corporation run by a board of governors in 1971 following passage of the Postal Reorganization Act.

J.D. Thomas said the Postal Service Act was shaped in part by the desire to avoid censorship employed by the Crown to try to suppress their political opponents in colonial times. He also claimed that “the promise of mail delivery [helped] grow the nation and economy instead of serving only existing communities.” He illustrated its importance to people on the frontier by discussing the role of mail in the lives of people around Royalton, NY. Before they got a post office in 1826, “The neighbors would club together, put a boy on a horse, and about once a month he could be seen wending his way through forest and stream, … to get, perchance, half a dozen letters and papers for four times that number of families. … [W]hen he returned, if no tidings came from loved ones, they did their best to suppress the silent tears that would often betray their sadness.”

Researchers have claimed that the widespread availability of newspapers contributed to a high literacy rate in the US. This in turn helped increase the rate of economic growth, thereby contributing to its dominant position in the international economy today.

The postal system played a crucial role in national expansion. It facilitated expansion into the West by creating an inexpensive, fast, convenient communication system. Letters from early settlers provided information and boosterism to encourage increased migration to the West, helped scattered families stay in touch and provide assistance, assisted entrepreneurs in finding business opportunities, and made possible regular commercial relationships between merchants in the west and wholesalers and factories back east. The postal service likewise assisted the Army in expanding control over the vast western territories. The widespread circulation of important newspapers by mail, such as the New York Weekly Tribune, facilitated coordination among politicians in different states. The postal service helped integrate established areas with the frontier, creating a spirit of nationalism and providing a necessary infrastructure.

The Post Office in the 19th century was a major source of federal patronage. Local postmasterships were rewards for local politicians—often the editors of party newspapers. About 3/4 of all federal civilian employees worked for the Post Office. In 1816 it employed 3341 men, and in 1841, 14,290. The volume of mail expanded much faster than the population, as it carried annually 100 letters and 200 newspapers per 1000 white population in 1790, and 2900 letters and 2700 newspapers per thousand in 1840.

Rufus Easton was appointed by Thomas Jefferson first postmaster of St. Louis under the recommendation of Postmaster General Gideon Granger. Rufus Easton was the first postmaster and built the first post office west of the Mississippi. At the same time Easton was appointed by Thomas Jefferson, judge of Louisiana Territory, the largest territory in North America. Bruce Adamson wrote that: “Next to Benjamin Franklin, Rufus Easton was one of the most colorful people in United States Postal History.” It was Easton who educated Abraham Lincoln’s Attorney General, Edward Bates. In 1815 Edward Bates moved into the Easton home and lived there for years at Third and Elm. Today this is the site of the Jefferson Memorial Park. In 1806 Postmaster General Gideon Granger wrote a three-page letter to Easton, begging him not to partake in a duel with vice-president Aaron Burr. Two years earlier it was Burr who had shot and killed Alexander Hamilton.

In 1852, Easton’s son, Major-General Langdon Cheves Easton, was commissioned by William T. Sherman, at Fort Union to deliver a letter to Independence, Missouri. Sherman wrote: “In the Spring of 1852, General Sherman mentioned that the quartermaster, Major L.C. Easton, at Fort Union, New Mexico, had occasion to send some message east by a certain date, and contracted with Aubrey to carry it to the nearest post office (then Independence, Missouri), making his compensation conditional on the time consumed. He was supplied with a good horse, and an order on the outgoing trains for exchange. Though the whole route was infested with hostile Indians, and not a house on it, Aubrey started alone with his rifle. He was fortunate in meeting several outward-bound trains, and thereby made frequent changes of horses, some four or five, and reached Independence in six days, having hardly rested or slept the whole way.”

To cover long distances, the Post Office used a hub-and-spoke system, with Washington as the hub and chief sorting center. By 1869, with 27,000 local post offices to deal with, it had changed to sorting mail en route in specialized railroad mail cars, called Railway Post Offices, or RPOs. The system of postal money orders began in 1864. Free mail delivery began in the larger cities in 1863.

The Post Office Department was enlarged during the tenure of President Andrew Jackson. As the Post Office expanded, difficulties were experienced due to a lack of employees and transportation. The Post Office’s employees at that time were still subject to the so-called “spoils” system, where faithful political supporters of the executive branch were appointed to positions in the post office and other government corporations as a reward for their patronage. These appointees rarely had prior experience in postal service and mail delivery. This system of political patronage was replaced in 1883, after passage of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act.

In 1823, ten years after the Post Office had first begun to use steamboats to carry mail between post towns where no roads existed, waterways were declared post roads. Once it became clear that the postal system in the United States needed to expand across the entire country, the use of the railroad to transport the mail was instituted in 1832, on one line in Pennsylvania. All railroads in the United States were designated as post routes, after passage of the Act of July 7, 1838. Mail service by railroad increased rapidly thereafter.

Before the introduction of stamps, it was the recipient of mail — not the sender — who generally paid the cost of postage, giving the fee directly to the postman on delivery. The task of collecting money for letter after letter greatly slowed the postman on his route. Moreover, the addressee would not infrequently refuse a piece of mail, which then had to be taken back to the Post Office (post office budgets always allowed for an appreciable volume of unpaid-for mail). Only occasionally did a sender pay delivery costs in advance, an arrangement that usually required a personal visit to the Post Office. To be sure, postmasters allowed some citizens to run charge accounts for their delivered and prepaid mail, but bookkeeping on these constituted another inefficiency.

Postage stamps revolutionized this process, leading to universal prepayment; but a precondition for their issue by a nation was the establishment of standardized rates for delivery throughout the country. If postal fees were to remain (as they were in many lands) a patchwork of many different jurisdictional rates, the use of stamps would produce only limited gains in efficiency, for postal clerks would still have to spend time calculating the rates on many letters: only then would senders know how much postage to put on them.

The introduction of the first postage stamps in Great Britain in May 1840 was received with great interest in the United States (and around the world). Later that year, Daniel Webster rose in the U.S. Senate to recommend that the recent English postal reforms — standardized rates and the use of postage stamps — be adopted in America.

It would be private enterprise, however, that brought stamps to the U. S. On February 1, 1842, a new carrier service called “City Despatch Post” began operations in New York City, introducing the first adhesive postage stamp ever produced in the western hemisphere, which it required its clients to use for all mail. This stamp was a 3-cent issue bearing a rather amateurish drawing of George Washington, printed from line engraved plates in sheets of 42 images. The company had been founded by Henry Thomas Windsor, a London merchant who at the time was living in Hoboken, New Jersey. Alexander M. Greig was advertised as the post’s “agent,” and as a result, historians and philatelists have tended to refer to the firm simply as “Greig’s City Despatch Post,” making no mention of Windsor. In another innovation, the company placed mail-collection boxes around the city for the convenience of its customers.

A few months after its founding, the City Despatch Post was sold to the U.S. Government, which renamed it the “United States City Despatch Post.” The government began operation of this local post on August 16, 1842, under an Act of Congress of some years earlier that authorized local delivery. Greig, retained by the Post Office to run the service, kept the firm’s original Washington stamp in use, but soon had its lettering altered to reflect the name change. In its revised form, this issue accordingly became the first postage stamp produced under the auspices of a government in the western hemisphere.

An Act of Congress of March 3, 1845 (effective July 1, 1845), established uniform (and mostly reduced) postal rates throughout the nation, with a uniform rate of five cents for distances under 300 miles (500 km) and ten cents for distances between 300 and 3000 miles. However, Congress did not authorize the production of stamps for nationwide use until 1847. Local postmasters realized that standard rates now made it feasible to produce and sell “provisional” issues for prepayment of uniform postal fees, and printed these in bulk. Such provisionals included both prepaid envelopes and stamps, mostly of crude design, the New York Postmaster’s Provisional being the only one of quality comparable to later stamps.

The provisional issues of Baltimore were notable for the reproduced signature of the city’s postmaster — James M. Buchanan (1803-1876), a cousin to President James Buchanan. All provisional issues are rare, some inordinately so: at a Siegel Gallery auction in New York on March 2012, an example of the Millbury provisional fetched $400,000, while copies of the Alexandria and Annapolis provisionals each sold for $550,000. Eleven cities printed provisional stamps in 1845 and 1846.

The 1845 Congressional act did, in fact, raise the rate on one significant class of mail: the so-called “drop letter” — a letter delivered from the same post office that collected it. Previously one cent, the drop letter rate became two cents.

Congress finally provided for the issuance of stamps by passing an act on March 3, 1847, and the Postmaster-General immediately let a contract to the New York City engraving firm of Rawdon, Wright, Hatch, and Edson. The first stamp issue of the U.S. was offered for sale on July 1, 1847, in New York City, with Boston receiving stamps the following day and other cities thereafter. They consisted of an engraved 5-cent red brown stamp depicting Benjamin Franklin (the first postmaster of the U.S.), and a 10-cent value in black with George Washington. Like all U.S. stamps until 1857, they were imperforate.

The 5-cent stamp paid for a letter weighing less than one-half ounce and traveling up to 300 miles, the 10-cent stamp for deliveries to locations greater than 300 miles, or, twice the weight deliverable for the 5-cent stamp. Each stamp was hand engraved in what is believed to be steel, and laid out in sheets of 200 stamps. The 5-cent stamp is often found today with very poor impressions because the type of ink used contained small pieces of quartz that wore down the steel plates used to print the stamp. On the other hand, most 10-cent stamps are of strong impressions. A fresh and brilliantly printed 5-cent stamp is prized by collectors.

The use of stamps was optional: letters could still be sent requiring payment of postage on delivery. Indeed, the post office issued no 2-cent value for prepaying drop letters in 1847, and these continued to be handled as they had been. Nevertheless, many Americans took up using stamps; about 3,700,000 of the 5¢ and about 865,000 of the 10¢ were sold, and enough of those have survived to ensure a ready supply for collectors, although the demand is such that a very fine 5-cent (Scott #1) sells for around $500 as of 2003, and the 10-cent (Scott #2) in very fine condition sells for around $1,400 in used form. Unused stamps are much scarcer, fetching around $6,000 and $28,000 respectively, if in very fine condition. One can pay as little as 5 to 10 percent of these figures if the stamps are in poor condition.

In 1847, the U.S. Mail Steamship Company acquired the contract which allowed it to carry the U.S. mails from New York, with stops in New Orleans and Havana, to the Isthmus of Panama for delivery in California. The same year, the Pacific Mail Steamship Company had acquired the right to transport mail under contract from the United States Government from the Isthmus of Panama to California. In 1855, William Henry Aspinwall completed the Panama Railway, providing rail service across the Isthmus and cutting to three weeks the transport time for the mails, passengers and goods to California. This remained an important route until the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869.

The post office had become so efficient by 1851 that Congress was able to reduce the common rate to three cents (which remained unchanged for over thirty years), necessitating a new issue of stamps. Moreover, the common rate now applied to letters carried up to 3000 miles. This rate, however, only applied to prepaid mail: a letter sent without a stamp still cost the recipient five cents — clear evidence that Congress envisioned making stamp use mandatory in the future (it did so in 1855). The 1-cent drop-letter rate was also restored, and Post Office plans did not at first include a stamp for it; later, however, an essay for a 6-cent Franklin double-weight stamp was converted into a drop-letter value. Along with this 1¢ stamp, the post office initially issued only two additional denominations in the series of 1851: 3¢ and 12¢, the three stamps going on sale that July and August.

Since the 1847 stamps no longer conformed to any postal rate, they were declared invalid after short period during which the public could exchange old stamps for new ones. Ironically, however, within a few years the Post Office found that stamps in the old denominations were needed after all, and so, added a 10-cent value to the series in 1855, followed by a 5-cent stamp the following year. The full series included a 1-cent profile of Franklin in blue, a 3-cent profile of Washington in red brown, a 5-cent portrait of Thomas Jefferson, and portraits of Washington for 10-cent green and 12-cent black values.

The 1-cent stamp achieved notoriety, at least among philatelists, because production problems (the stamp design was too tall for the space provided) led to a welter of plate modifications done in piecemeal fashion, and there are no fewer than seven major varieties, ranging in price from $100 to $200,000 (the latter for the only stamp of the 200 images on the first plate that displays the design’s top and bottom ornamentation complete). Sharp-eyed collectors periodically find the rare types going unrecognized.

Perforations on stamps were introduced in 1857 and in 1860 24-cent, 30-cent and 90-cent values (with still more images of Washington and Franklin) were issued for the first time. These higher denominations, especially the 90-cent value, were available for such a short time (a little over a year) that they had virtually no chance of being used. The 90-cent stamp used is a very rare item, and so frequently forged that authorities counsel collectors to shun canceled copies that lack expert certification.

In 1860, the U.S. Post Office incorporated the services of the Pony Express to get mail to and from San Francisco, an important undertaking with the outbreak of the Civil War the following year as a communication link between Union forces and San Francisco and the West Coast was badly needed. The Pony Express Trail from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California, was 1,840 miles long. Upon arrival in Sacramento, the U.S. mail was placed on a steamer and continued down the Sacramento River to San Francisco for a total of 1,966 miles. The Pony Express was a short-lived enterprise, remaining in operation for only 18 months. Consequently, there is little surviving Pony Express mail today, only 250 examples known in existence.

In February 1861, a congressional act directed that “cards, blank or printed. . .shall also be deemed mailable matter, and charged with postage at the rate of one cent an ounce.” Private companies soon began issuing post cards, printed with a rectangle in the top right corner where the stamp was to be affixed. The Post Office Department would not produce pre-stamped “postal cards” for another dozen years.

The outbreak of the American Civil War threw the postal system into turmoil. On April 13, 1861, (the day after the firing on Fort Sumter) John H. Reagan, postmaster-general of the Confederate States of America, ordered local postmasters to return their U.S. stamps to Washington D.C. (although it is unlikely that many did so), while in May the Union decided to withdraw and invalidate all existing U.S. stamps, and to issue new stamps. Confederate post offices were left without legitimate stamps for several months, and while many reverted to the old system of cash payment at the post office, over 100 post offices across the South came up with their own provisional issues. Many of these are quite rare, with only single examples surviving of some types. Eventually the Confederate government issued its own stamps; see stamps and postal history of the Confederate States.

In the North, the new stamp designs became available in August, and old stamps were accepted in exchange, with different deadlines for replacement set for different regions of the country, first ranging from September 10 to November 1, later modified to November 1 to January 1, 1862. The whole process was very confusing to the public, and there are number of covers from 1862 and later with 1857 stamps and bearing the marking OLD STAMPS NOT RECOGNIZED.

The 1861 stamps had in common the letters “U S” in their design. To make them differentiable from the older stamps at a glance, all were required to have their values expressed in Arabic numerals (in the previous series, Arabic numerals had appeared only on the 30-cent stamp). The original issue included all the denominations offered in the previous series: 1 cent, 3 cents, 5 cents, 10 cents, 12 cents, 24 cents, 30 cents and 90 cents. Numerals apart, several of these are superficially similar to their earlier counterparts — particularly because Franklin, Washington and Jefferson still appear on the same denominations as previously. Differences in the design of the frames are more readily apparent.

A 2-cent stamp in black featuring Andrew Jackson was issued in 1863 and is now known to collectors as the “Black Jack”. A black 15-cent stamp depicting the recently assassinated Abraham Lincoln was issued in 1866, and is generally considered part of the same series. Although it was not officially described as such, and the 15-cent value was chosen to cover newly established fee for registered letters, many philatelists consider this to be the first memorial stamp ever issued.

The war greatly increased the amount of mail in the North; ultimately about 1,750,000,000 copies of the 3-cent stamp were printed, and a great many have survived to the present day, typically selling for 2-3 dollars apiece. Most are rose-colored; pink versions are much rarer and quite expensive, especially the “pigeon blood pink”, which goes for $3,000 and up.

The stamps of the 1861 series, unlike those of the two previous issues, remained valid for postage after they had been superseded—as has every subsequent United States stamp.

Widespread hoarding of coins during the Civil War created a shortage, prompting the use of stamps for currency. To be sure, the fragility of stamps made them unsuitable for hand-to-hand circulation, and to solve this problem, John Gault invented the encased postage stamp in 1862. A normal U. S. stamp was wrapped around a circular cardboard disc and then placed inside a coin-like circular brass jacket. A transparent mica window in the jacket allowed the face of the stamp to be seen. All eight denominations available in 1861-62, ranging from 1 cent to 90 cents, were offered in encased versions. Raised lettering on the metal backs of the jackets often advertised the goods or services of business firms; these included the Aerated Bread Company; Ayers Sarsaparilla and Cathartic Pills; Burnett’s Cocoaine; Sands Ale; Drake’s Plantation Bitters; Buhl & Co. Hats and Furs; Lord & Taylor; Tremont House, Chicago; Joseph L. Bates Fancy Goods; White the Hatter, New York City; and Ellis McAlpin & Co. Dry Goods, Cincinnati.

Railroad companies greatly expanded mail transport service after 1862, and the Railway Mail Service was inaugurated in 1869. Rail cars designed to sort and distribute mail while rolling were soon introduced. RMS employees sorted mail “on-the-fly” during the journey, and became some of the most skilled workers in the postal service. An RMS sorter had to be able to separate the mail quickly into compartments based on its final destination, before the first destination arrived, and work at the rate of 600 pieces of mail an hour. They were tested regularly for speed and accuracy.

During the 1860s, the postal authorities became concerned about postage stamp reuse. Although there is little evidence that this occurred frequently, many post offices had never received any canceling devices. Instead, they improvised a canceling process by scribbling on the stamp with an ink pen (“pen cancellation”), or whittling designs in pieces of cork, sometimes very creatively (“fancy cancels”), to mark the stamps. However, since poor-quality ink could be washed from the stamp, this method would only have been moderately successful. A number of inventors patented various ideas to attempt to solve the problem.

The Post Office Department eventually adopted the grill, a device consisting of a pattern of tiny pyramidal bumps that would emboss the stamp, breaking up the fibers so that the ink would soak in more deeply, and thus be harder to clean off. While the patent survives (No. 70,147), much of the actual process of grilling was not well documented, and there has been considerable research trying to recreate what happened and when. Study of the stamps shows that there were eleven types of grill in use, distinguished by size and shape (philatelists have labeled them with letters A-J and Z), and that the practice started some time in 1867 and was gradually abandoned after 1871. A number of grilled stamps are among the great rarities of US philately. The United States 1-cent Z grill was long thought to be the rarest of all U.S. stamps, with only two known to exist. In 1961, however, it was discovered that the 15-cent stamp of the same series also existed in a Z grill version; this stamp is just as rare as the 1-cent, for only two examples of the 15-cent Z grill are known. Rarer still may be the 30-cent stamp with the I Grill, the existence of which was discovered only recently: as of October 2011, only one copy is known.

In 1868, the Post Office contracted with the National Bank Note Company to produce new stamps with a variety of designs. These came out in 1869, and were notable for the variety of their subjects; the 2-cent value depicted a Pony Express rider, the 3-cent stamp portrayed a locomotive, the 12-cent denomination pictured the steamship Adriatic, the 15-cent stamp showed the landing of Christopher Columbus, and the 24-cent value marked the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

Other innovations in what has become known as the 1869 Pictorial Issue included the first use of two-color printing on U.S. stamps, and as a consequence the first invert errors. Although popular with collectors today, the unconventional stamps were not very popular among a population who was accustomed to postage that bore classic portrayals of Washington, Franklin and other forefathers. Consequently, the Post Office recalled all remaining stocks after one year.

The Post Office Act (17 Stat. 283, enacted June 8, 1872) formally incorporated the United States Post Office Department into the United States Cabinet. It is also notable for §148 which made it illegal to send any obscene or disloyal materials through the mail, to be the foundation of the later Comstock Act of 1873.

The postage stamps issued in the 1870s and 1880s are collectively known as the “Bank Notes” because they were produced by the National Bank Note Company, the Continental Bank Note Company, then the American Bank Note Company. After the 1869 fiasco with pictorial stamp issues, the new Postmaster-General decided to base a series of stamps on the “heads, in profile, of distinguished deceased Americans” using “marble busts of acknowledged excellence” as models. George Washington was returned to the normal-letter-rate stamp: he had played that role in the issues of 1851 and 1861 and would continue to do so in every subsequent definitive set until the Presidential Series of 1938.

The large “Bank Notes” stamps did not represent a total retreat to past practices, for the range of celebrated Americans was widened beyond Franklin and various presidents to include notables such as Henry Clay and Oliver Hazard Perry. Moreover, while images of statesmen had provided the only pictorial content of pre-1869 issues, the stamps did not entirely exclude other representative images. Two denominations of the series accompanied their portraits with iconographic images appropriate to the statesmen they honored: rifles, a cannon and cannonballs appeared in the bottom corners of the 24-cent issue devoted to General Winfield Scott, while the 90-cent stamp framed Admiral Oliver Perry within a nautically hitched oval of rope and included anchors in the bottom corners of its design. National first printed these, then in 1873 Continental received the contract — and the plates that National used. Continental added secret marks to the plates of the lower values, distinguishing them from the previous issues. The American Bank Note Company acquired Continental in 1879 and took over the contract, printing similar designs on softer papers and with some color changes. Major redesigning, however, came only in 1890, when the American Bank Note Company issued a new series in which stamp-size was reduced by about 10% (the so-called “Small Bank Notes”).

In 1873, the Post Office began producing a pre-stamped post card. One side was printed with a Liberty-head one-cent stamp design, along with the words “United States Postal Card” and three blank lines provided for the mailing address. Six years later, it introduced a series of seven Postage Due stamps in denominations ranging from 1 cent to 50 cents, all printed in the same brownish-red color and conforming to the same uniform and highly utilitarian design, with their denominations rendered in numerals much larger than those found on definitive stamps. The design remained unchanged until 1894, and only four different postage due designs have appeared to date.

In 1883, the first-class letter rate was reduced from 3 cents to 2 cents, prompting a redesign of the existing 3-cent green Washington stamp, which now became a 2-cent brown issue.

In 1885 the Post Office established a Special Delivery service, issuing a ten-cent stamp depicting a running messenger, along with the wording “secures immediate delivery at a special delivery office.” Initially, only 555 such offices existed but the following year all U. S. Post Offices were obliged to provide the service — an extension not, however, reflected on the Special Delivery stamp until 1888, when the words “at any post office” appeared on its reprint. On stamps of future years, the messenger would be provided the technological enhancements of a bicycle (1902) a motorcycle (1922) and a truck (1925). Although the last new U.S. Special Delivery stamp appeared issued in 1971, the service was continued until 1997, by which time it had largely been supplanted by Priority Mail delivery, introduced in 1989. The 1885 Special Delivery issue was the first U.S. postage stamp designed in the double-width format. Eight years later, this shape would be chosen for the Columbian Exposition commemoratives, as it offered appropriate space for historical tableaux. The double-width layout would subsequently be employed in many United States commemorative stamps.

Parcel Post service began with the introduction of International Parcel Post between the U.S. and foreign countries in 1887. That same year, the U.S. Post Office and the Postmaster General of Canada established parcel-post service between the two nations. A bilateral parcel-post treaty between the independent (at the time) Kingdom of Hawaii and the United States was signed on 19 December 1888 and put into effect early in 1889. Parcel-post service between the U.S. and other countries grew with the signing of successive postal conventions and treaties. While the Post Office agreed to deliver parcels sent into the country under the Universal Postal Union treaty, it did not institute a domestic parcel-post service for another twenty-five years.

The World Columbian Exposition of 1893 commemorated the 400th anniversary of the landing of Christopher Columbus in the Americas. The Post Office got in on the act, issuing a series of 16 stamps depicting Columbus and episodes in his career, ranging in value from 1 cent to 5 dollars (a princely sum in those days). The stamps were interesting and attractive, designed to appeal to not only postage stamps collectors but to historians, artists and of course the general public who bought them in record numbers because of the fanfare of the Columbian Exposition of the World’s Fair of 1892 in Chicago, Illinois. They were quite successful (a great contrast to the pictorials of 1869), with lines spilling out of the nation’s post offices to buy the stamps. They are prized by collectors today with the $5 denomination, for example, selling for between $1,500 to $12,500 or more, depending upon the condition of the stamp being sold.

Another release in connection with the Columbian series was a reprint of the 1888 Special Delivery stamp, now colored orange (reportedly, to prevent postal clerks from confusing it with the 1-cent Columbian). After sales of the series ceased, the Special Delivery stamp reappeared in its original blue.

Also during 1893, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing competed for the postage stamp printing contract, and won it on the first try. For the postage issues of the 1894 series, the Bureau took over the plates of the 1890 small banknote series but modified them by adding triangles to the upper corners of the designs. Three new designs were needed, because the Post Office elected to add $1, $2 and $5 stamps to the series (previously, the top value of any definitive issue had been 90 cents). On many of the 1894 stamps, perforations are of notably poor quality, but the Bureau would soon make technical improvements.

In 1895, counterfeits of the 2-cent value were discovered, which prompted the BEP to begin printing stamps on watermarked paper for the first time in U.S. postal history. The watermarks imbedded the logo U S P S into the paper in double-lined letters. The Bureau’s definitive issues of the 1890s consisted of 13 different denominations ranging from 1 cent to 5 dollars, and may be differentiated by the presence or absence of this watermark, which would appear on all U. S. postage stamps between 1895 and 1910. The final issue of 1898 altered the colors of many denominations to bring the series into conformity with the recommendations of the Universal Postal Union. The aim was to ensure that in all its member nations, stamps for given classes of mail would appear in the same colors. Accordingly, U.S. 1-cent stamps (postcards) were now green and 5-cent stamps (international mail) were now blue, while 2-cent stamps remained red. As a result, it was also necessary to replace the blue and green on higher values with other colors. U.S. postage continued to reflect this color-coding quite strictly until the mid-1930s, continuing also in the invariable use of purple for 3-cent stamps.

The advent of Rural Free Delivery (RFD) in the U.S. in 1896 greatly increased the volume of mail shipped nationwide, and motivated the development of more efficient postal transportation systems. Many rural customers took advantage of the R.F.D. (and, later, Parcel Post) to order goods and products from businesses located hundreds of miles away in distant cities for delivery by mail.

In 1898, the Trans-Mississippi Exposition opened in Omaha, Nebraska, and the Post Office Department was ready with a nine-stamp commemorative series. The were originally to be two-toned, with black vignettes surrounded by colored frames, but the BEP, its resources overtaxed by the needs of the Spanish–American War, simplified the printing process, issuing the stamps in single colors. They were received favorably, though with less excitement than the Columbians; but like the Columbians, they are today prized by collectors, and many consider the $1 “Western Cattle in Storm” the most attractive of all U.S. stamps.

Collectors, still smarting from the expense of the Columbian stamps, objected that inclusion of $1 and $2 issues in the Trans-Mississippi series presented them with an undue financial hardship. Accordingly, the next stamp series commemorating a prominent exposition, the Pan-American Exposition held in Buffalo, New York in 1901, was considerably less costly, consisting of only six stamps ranging from in value from 1 cent to 10 cents. The result, paradoxically, was a substantial increase in Post Office profits; for, while the higher valued Columbians and Trans-Mississippis had sold only about 20,000 copies apiece, the public bought well over five million of every Pan-American denomination. In the Pan-American series the Post Office realized the plan for two-toned stamps that it had been obliged to abandon during the production of the Trans-Mississippi issue. Upside-down placement of some sheets during the two-stage printing process resulted in the so-called Pan-American invert errors on rare copies of the 1¢, 2¢ and 4¢ stamps.

The definitive stamps issued by the U.S. Post Office in 1902–1903 were markedly different in their overall designs from the regular definitive stamps released over the previous several decades. Among the prominent departures from tradition in these designs was that the names of the subjects were printed out, along with their years of birth and death. Unlike any definitive stamps ever issued before, the 1902–03 issues also had ornate sculptural frame work redolent of Beaux-Arts architecture about the portrait, often including allegorical figures of different sorts, with several different types of print used to denote the country, denominations and names of the subjects. This series of postage stamps were the first definitive issues to be entirely designed and printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, and their Baroque revival style is much akin to that of the Pan-American commemoratives the Bureau had issued in 1901. There are fourteen denominations ranging from 1 cent to 5 dollars. The 2-cent George Washington stamp appeared with two different designs (the original version was poorly received) while each of the other values has its own individual design. This was the first U.S. definitive series to include the image of a woman: Martha Washington, who appeared on the 8-cent stamp.

In these years, the postal service continued to produce commemorative sets in conjunction with important national expositions. The Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri in 1904 prompted a set of five stamps, while a trio of stamps commemorated the Jamestown Exposition, held in Norfolk, Virginia in 1907.

The long-running Washington-Franklin series of stamps was begun in 1908. Although there were only two central images, a profile of Washington and one of Franklin, many subtle variants appeared over the years. The Post Office Department experimented with half-a-dozen different perforation sizes, two kinds of watermarking, three printing methods, and large numbers of values, all adding to several hundred distinct types identified by collectors. Some are quite rare, but many are extremely common; this was the era of the postcard craze, and almost every antique shop in the U.S. will have some postcards with green 1-cent or red 2-cent stamps from this series. In 1910, the Post Office began phasing out the double-lined watermark, replacing it by the same U S P S logo in smaller single-line letters. Watermarks were discontinued entirely in 1916.

Toward the beginning of the Washington-Franklin era, in 1909, the Post Office issued its first individual commemorative stamps — three single 2-cent issues honoring, respectively, the Lincoln Centennial, the Alaska-Yukon Exposition, and the tercentennial/centennial Hudson-Fulton Celebration in New York. A four-stamp series commemorating the Panama–Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, California appeared in 1913, but no further commemoratives were issued until after World War I. The Lincoln Centennial’s portrait format distinguished it from all other commemoratives released between 1893 and 1926, which were produced exclusively in landscape format. The next U. S. commemorative in portrait orientation would be the Vermont Sesquicentennial issue of 1927, and many have appeared since.

In 1912, carrier service was announced for establishment in towns of second and third class with $100,000 appropriated by Congress. From January 1, 1911, until July 1, 1967, the United States Post Office Department operated the United States Postal Savings System. An Act of Congress of June 25, 1910, established the Postal Savings System in designated Post Offices, effective January 1, 1911. The legislation aimed to get money out of hiding, attract the savings of immigrants accustomed to the postal savings system in their native countries, provide safe depositories for people who had lost confidence in banks, and furnish more convenient depositories for working people. The law establishing the system directed the Post Office Department to redeposit most of the money in the system in local banks, where it earned 2.5 percent interest.

The system paid 2-percent interest per year on deposits. The half percent difference in interest was intended to pay for the operation of the system. Certificates were issued to depositors as proof of their deposit. Depositors in the system were initially limited to hold a balance of $500, but this was raised to $1,000 in 1916 and to $2,500 in 1918. The initial minimum deposit was $1. In order to save smaller amounts for deposit, customers could purchase a 10-cent postal savings card and 10-cent postal savings stamps to fill it. The card could be used to open or add to an account when its value, together with any attached stamps, amounted to one or more dollars, or it could be redeemed for cash. At its peak in 1947, the system held almost $3.4 billion in deposits, with more than four million depositors using 8,141 postal units.

In January 1913, Postmaster General Frank H. Hitchcock introduced domestic parcel post service — a belated development, given that international parcel post service between the United States and other countries began in 1887. A series of twelve Parcel Post stamps intended for this service had already been released in December 1912, ranging in denomination from 1 cent to 1 dollar. All were printed in red and designed in the wide Columbian format. The eight lowest values illustrated aspects of mail handling and delivery, while higher denominations depicted such industries as Manufacturing, Dairying and Fruit Growing. Five green Parcel Post Postage Due stamps appeared concurrently. It soon became obvious that none of these stamps was needed: parcel postage could easily be paid by definitive or commemorative issues, and normal postage due stamps were sufficient for parcels. When original stocks ran out, no reprints appeared, nor were replacements for either group ever contemplated. However, one denomination introduced in the Parcel Post series — 20 cents — had proved useful, and the Post Office added this value to the Washington-Franklin issues in 1914, along with a 30-cent stamp.

From the 1910s to the 1960s, many college students and others used parcel post to mail home dirty laundry, as doing so was less expensive than washing the clothes themselves. After four-year-old Charlotte May Pierstorff was mailed from her parents to her grandparents in Idaho in 1914, mailing of people was prohibited. In 1917, the Post Office imposed a maximum daily mailable limit of two hundred pounds per customer per day after a business entrepreneur, W.H. Coltharp, used inexpensive parcel-post rates to ship more than eighty thousand masonry bricks some four hundred seven miles via horse-drawn wagon and train for the construction of a bank building in Vernal, Utah.

The advent of parcel post also led to the growth of Mail order businesses that substantially increased rural access to modern goods over what was typically stocked in local general stores.

The Post Office Department played a role during World War I, enacting the Espionage and Trading with the Enemy Acts. It also monitored foreign mail and acted as counter-espionage to help secure allied victory.

On November 3, 1917, the normal letter rate was raised from 2 cents to 3 cents in support of the war effort. The rate hike was reflected in the first postwar commemorative — a 3-cent “victory” stamp released on March 3, 1919 (not until July 1 would postal fees return to peacetime levels). Only once before (with the Lincoln Memorial issue of 1909) had the Post Office issued a commemorative stamp unconnected to an important national exposition; and the appearance of the Pilgrim Tercentenary series in 1920 confirmed that a new policy was developing: the Post Office would no longer need the pretext of significant patriotic trade fairs to issue commemoratives: they could now freely produce stamps commemorating the anniversaries of any notable historical figures, organizations or events.

n August 12, 1918, the Post Office Department took over the airmail service from the United States Army Air Service (USAAS). Assistant Postmaster General, Otto Praeger, appointed Benjamin B. Lipsner to head the civilian-operated Air Mail Service. One of Lipsner’s first acts was to hire four pilots, each with at least 1,000 hours flying experience, paying them an average of $4,000 per year ($63.7 thousand today). The Post Office Department used new Standard JR-1B biplanes specially modified to carry the mail while the war was still in progress, but following the war operated mostly World War I surplus military de Havilland DH-4 aircraft.

During 1918, the Post Office hired an additional 36 pilots. In its first year of operation, the Post Office completed 1,208 airmail flights with 90 forced landings. Of those, 53 were due to weather and 37 to engine failure. By 1920, the Air Mail service had delivered 49 million letters. Domestic air mail became obsolete in 1975, and international air mail in 1995, when the USPS began transporting First-Class mail by air on a routine basis.

The stamps of the 1920s were dominated by the Series of 1922, the first new design of definitive stamps to appear in a generation. The lower values mostly depicted various presidents, with the 5-cent value particularly intended as a memorial of the recently deceased Theodore Roosevelt, while the higher values included an “American Indian” (Hollow Horn Bear), the Statue of Liberty, Golden Gate (without the bridge, which had yet to be built), Niagara Falls, a bison, the Lincoln Memorial and so forth. Higher values of the series (from 17 cents through 5 dollars) were differentiated from the cheaper stamps by being designed in horizontal (landscape) rather than vertical format, an idea carried over from the “big Bens” of the Washington-Franklin series.

Stamp printing was switching from a flat plate press to a rotary press while these stamps were in use, and most come in two perforations as a result; 11 for flat plate, and 11×10½ for rotary. In 1929, theft problems in the Midwest led to the Kansas-Nebraska overprints on the regular stamps.

From 1924 on, commemorative stamps appeared every year. The 1920s saw a number of 150th anniversaries connected with the American Revolutionary War, and a number of stamps were issued in connection with those. These included the first U.S. souvenir sheet, for the Battle of White Plains sesquicentennial, and the first overprint, reading MOLLY / PITCHER, the heroine of the Battle of Monmouth.

The German zeppelins were of much interest during this period, and in 1930 the Department issued special stamps to be used on the Pan-American flight of Graf Zeppelin. Although the Graf Zeppelin stamps are today highly prized by collectors as masterpieces of the engraver’s art, in 1930 the recent stock market crash meant that few were able to afford these stamps (the $4.55 value for the set represented a week’s food allowance for a family of four). Less than 10 percent of the 1,000,000 of each denomination issued were sold and the remainders were incinerated (the stamps were only available for sale to the public from April 19, 1930, to June 30, 1930). It is estimated that less than 8 percent of the stamps produced survive today and they remain the smallest U.S. issue of the twentieth century (only 229,260 of these stamps were ever purchased, and only 61,296 of the $2.60 stamp were sold).

In 1932, a set of 12 stamps was issued to celebrate George Washington’s 200th birthday anniversary. For the 2-cent value, which satisfied the normal letter rate, the most familiar Gilbert Stuart image of Washington had been chosen. After postal rates rose that July, this 2-cent red Washington was redesigned as a 3-cent stamp and issued in the purple color that now became ubiquitous among U.S. commemoratives.

In 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt became President. He was notable not only as an avid stamp collector in his own right (with a collection estimated at around 1 million stamps), but also for taking an interest in the stamp issues of the Post Office Department, working closely with Postmaster James Farley, the former Democratic Party Committee Chairman. Many designs of the 1930s were inspired or altered according to Roosevelt’s advice. A steady stream of commemoratives appeared during these years, including a striking 1934 issue of ten stamps presenting iconic vistas of ten National Parks — a set that has remained widely beloved. In a memorable sequence from Philip Roth’s novel The Plot Against America, the young protagonist dreams that his National Parks stamps, the pride and joy of his collection, have become disfigured with swastika overprints. Choosing an orange color for the 2-cent Grand Canyon tableau instead of the standard 2-cent carmine red, the Post Office departed from UPU color-coding for the first time.

With a philatelist in the White House, the Post Office catered to collectors as never before, issuing seven separate souvenir sheets between 1933 and 1937. In one case, a collectors’ series had to be produced as the result of a miscalculation. Around 1935, Postmaster Farley removed sheets of the National Parks set from stock before they had been gummed or perforated, giving these and unfinished examples of ten other issues to President Roosevelt and Interior Secretary Harold Ickes (also a philatelist) as curiosities for their collections. When word of these gifts got out, public outcries arose. Some accused Farley of a corrupt scheme to enrich Roosevelt and Ickes by creating valuable rarities for them at taxpayer expense. Stamp aficionados, in turn, demanded that these curiosities be sold to the public so that ordinary collectors could acquire them, and Farley duly issued them in bulk. This series of special printings soon became known as “Farley’s Follies.”

As the decade progressed, the purples used for 3-cent issues, although still ostensibly conforming to the traditional purple, displayed an increasingly wide variety of hues, and one 1940 issue, a 3-cent stamp commemorating the Pony Express, dispensed with purple entirely, appearing in a rust brown earth tone more suitable to the image of a horse and rider departing from a western rural post office.

The famous Presidential Issue, known as “Prexies” for short, came out in 1938. The series featured all 29 U.S. presidents through Calvin Coolidge, each of whom appeared in profile as a small sculptural bust. Values of 50 cents and lower were mono-colored; on the $1, $2, and $5 stamps the presidents’ images were printed in black on white, surrounded by colored lettering and ornamentation. Up through the 22-cent Cleveland stamp, the denomination assigned to each president corresponds to his position in the presidential roster: thus the first president, Washington, is on the 1-cent value, the seventeenth, Andrew Johnson, is on the 17-cent value, etc. Additional stamps depict Franklin (½ cent), Martha Washington (1½ cent), and the White House (4½ cents). Many of the values were included merely to place the presidents in proper numerical order and did not necessarily correspond to a postal rate; and one of the (difficult) games for Prexie collectors is to find a cover with, for instance, a single 16-cent stamp that pays a combination of rate and fees valid during the Prexies’ period of usage. Many such covers remain to be discovered; some sellers on eBay have been surprised to discover an ordinary-seeming cover bid up to several hundred dollars because it was one of the sought-after solo usages. The Presidential issue remained in distribution for many years. Not until 1954 did the Post Office begin replacing its values with the stamps of a new definitive issue, the Liberty series.

In 1940, the U.S. Post Office issued a set of 35 stamps, issued over the course of approximately ten months, commemorating America’s famous Authors, Poets, Educators, Scientists, Composers, Artists and Inventors. The Educators included Booker T. Washington, who now became the first African-American to be honored on a U.S. stamp. This series of Postage issues was printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. These stamps were larger in size than normal definitive issues, with only 280 stamp images contained on the printing plate (400 images was standard for the Presidential series). Notable also is the red-violet color chosen for the 3-cent stamps, a brighter hue than the traditional purple.

During World War II, production of new U. S. 3-cent commemorative stamps all but ceased. Among the three issues that appeared in 1942 was the celebrated Win the War stamp, which enjoyed enormously wide use, owing partly to patriotism and partly to the relative unavailability of alternatives. It presents an eagle posed in a “V” shape for victory surrounded by 13 stars. The eagle is grasping arrows, but has no olive branch.

The Overrun Countries series produced as a tribute to the thirteen nations that had been occupied by the Axis Powers. The thirteen stamps present full color images of the national flags of Poland, Czechoslovakia, Norway, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Greece, Yugoslavia, Albania, Austria, Denmark, and Korea, with the names of the respective countries written beneath. To the left of each flag appears the image of the phoenix, which symbolizes the renewal of life, and to its right appears a kneeling female figure with arms raised, breaking the shackles of servitude. These were released at intervals from June to December 1943, while the Korea flag stamp was released in November 1944. The stamps were denominated 5 cents, although the standard cost for a first class stamp was 3 cents. They were intended for use on V-mail, a means whereby mail intended for military personnel overseas was delivered with certainty. The service persons overseas used the same method for writing letters home, and the same process was used to reconstruct their letters, except that their postage was free. The two-cent surcharge on the V-mail letters helped pay for the additional expense of this method of delivery.

Because of the elaborate process necessary for the full-color printing, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing contracted with a private firm, the American Bank Note Company, to produce the Overrun Countries series — the first U. S. stamps to be printed by a private company since 1893. Uniquely among U. S. issues, the sheets lack the plate numbers usually printed on the selvage surrounding the stamps. In the places where the numbers normally appear on each sheet, the name of the country is substituted, engraved in capital letters.

The post-World War II stamp program followed a consistent pattern for many years: a steady stream of commemorative issues sold as single stamps at the first-class letter rate. While the majority of these were designed in the double-width format, an appreciable number issued in honor of individuals conformed instead to the format, size, general design style and red-violet hue used in the 1940 Famous Americans series.

The U.S. Post Office Department had become increasingly lax about employing purple for 3-cent stamps, and after the war, departures from that color in double-width commemoratives veritably became the rule rather than the exception (although UPU colors and purple for 3-cent stamps would continue to be used in the definitive issues of the next decades. Beginning in 1948, Congressional Representatives and Senators began to push the Department for stamps proposed by constituents, leading to a relative flood of stamps honoring obscure persons and organizations. Stamp issue did not again become well-regulated until the formation of the Citizens’ Stamp Advisory Committee (CSAC) in 1957.

The Liberty issue of 1954, deep in the Cold War, took a much more political slant than previous issues. The common first-class stamp was a 3-cent Statue of Liberty in purple, and included the inscription “In God We Trust”, the first explicit religious reference on a U.S. stamp (ten days before the issue of the 3-cent Liberty stamp, the words “under God” had been inserted into the Pledge of Allegiance). The Statue of Liberty appeared on two additional higher values as well, 8 cents and 11 cents, both of which were printed in two colors. The other stamps in the series included liberty-related statesmen and landmarks, such as Patrick Henry and Bunker Hill, although other subjects, (Benjamin Harrison, for example) seem unrelated to the basic theme.

In 1957, the American Flag was featured on a U. S. stamp for the first time. The Post Office had long avoided this image, fearing accusations that, in issuing stamps on which they would be defacing the flag by cancellation marks, they would be both committing and fomenting desecration. However, protests against this initial flag issue were muted, and the flag has remained a perennially popular U. S. stamp subject ever since.

The 3-cent rate for first-class had been unchanged since 1932, but by 1958 there were no more efficiency gains to keep the lid on prices, and the rate went to 4 cents, beginning a steady series of rate increases that reached 49 cents as of January 26, 2014.

The Prominent Americans series superseded the “Liberties” in the 1960s and proved the last definitive issue to conform to the Universal Postal Union color code. In the 1970s, they were replaced by the Americana series, in which colors became purely a matter of designer preference.

On March 18, 1970, postal workers in New York City — upset over low wages and poor working conditions, and emboldened by the Civil Rights movement — organized a strike against the United States government. The strike initially involved postal workers in only New York City, but it eventually gained support of over 210,000 United States Post Office Department workers across the nation. While the strike ended without any concessions from the Federal government, it did ultimately allow for postal worker unions and the government to negotiate a contract which gave the unions most of what they wanted, as well as the signing of the Postal Reorganization Act by President Richard Nixon on August 12, 1970. The Act replaced the cabinet-level Post Office Department with a new federal agency, the United States Postal Service, and took effect on July 1, 1971. The Postal Reorganization Act (at 39 U.S.C. § 410(c)(2)) exempts the USPS from Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) disclosure of “information of a commercial nature, including trade secrets, whether or not obtained from a person outside the Postal Service, which under good business practice would not be publicly disclosed”.

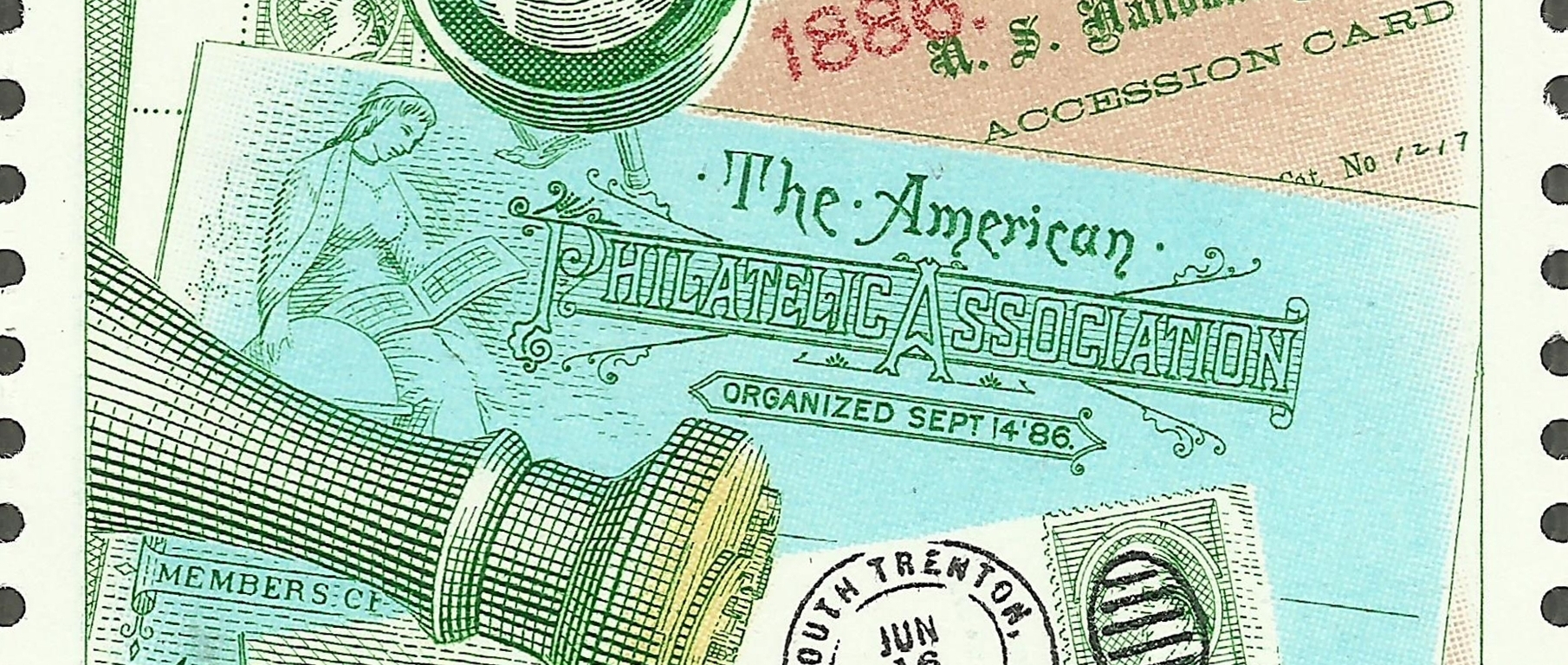

Scott #2198 was released in a booklet pane of four on January 23, 1986 (Scott #2201a, including one each of Scott #2198-2201) to promote the hobby of stamp collecting and the upcoming AMERIPEX ’86 international stamp exhibition , held in Chicago from May 22 through June 1, 1986. This was a joint issue with Sweden (Scott #1585-1588). The 22-cent stamp was lithographed and engraved and perforated 10 vertically on two sides. It features a partial sheet of U.S. Scott #213 — 2-cent green George Washington — along with one on cover (handstamped South Trenton, NY June 16, 1886) plus some philatelic memorabilia of the day (including a membership card of the American Philatelic Association, forerunner to the American Philatelic Society, which was established on September 14, 1886). Thus, the issue also commemorates the centennial of “America’s Stamp Club”.

3 thoughts on “U.S. Postal Service Act of 1792”