The United States Post Office Department’s Free City Delivery Service began in Cleveland, Ohio, on July 1, 1863. Joseph William Briggs, a postal clerk, had observed long lines of customers trying to keep warm as they inched toward his window in the winder of 1862. Many were women hoping for news of loved ones fighting in the Civil War. He convinced postal officials to deliver letters to Cleveland’s citizens for free with local businesses serving as staging areas for sorting customers’ mail. Encouraged by the results, officials expanded the service to other cities.

There’s been government-run or officially sanctioned postal service in North America since at least 1692, when Britain’s monarchy specifically appointed Thomas Neale, to set up a system in the colonies. A system of posting letters was in place by the next year, serving the Atlantic seaboard from New Hampshire to Virginia, and it was doing well enough that in 1707 the British government, smelling profits to be made, took proprietorship of the system. One of the first things the breakaway colonies did in 1775 — even before drafting a Declaration of Independence — was to recognize their own competing postal system with Benjamin Franklin at its head.

When the fledgling United States adopted the Constitution in 1783, the document called for Congress “to establish post offices and post roads” but was silent on any other services. In practice, the post offices of these days did not generally deliver mail to households or businesses directly, but only from post office to post office. A 1796 report to the House described the system:

“All the papers and packages delivered to distant customers and to be left at different offices and places, are put loose into the portmanteau with others, for subscribers less distant, and as often as the mail is opened the newspapers are thrown together out of the portmanteau in order to find the individual paper and package to be left at such office or place. At such times there is good reason to suppose papers and small packages are taken away by persons present at the opening of the portmanteau, to whom they are not directed, but without the knowledge or privity of the postmasters or carriers of the mail.”

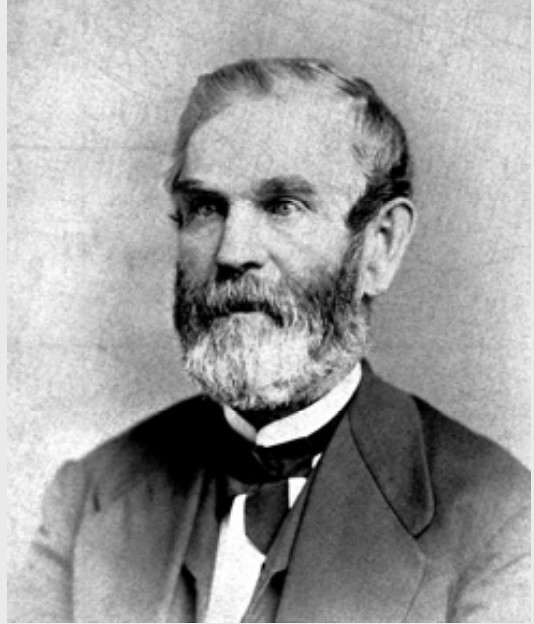

Before 1863, postage paid only for the delivery of mail from post office to post office. Addressees picked up their mail in most cases. In some cities, there was an option to pay the Post Office Department a two-cent fee for letter delivery to their homes or they could use private delivery firms. In his 1862 report to President Abraham Lincoln, U.S. Postmaster General Montgomery Blair had suggested that free delivery of mail by salaried letters carriers would “greatly accelerate deliveries, and promote the public convenience.”

Blair felt that if the process of mailing and receiving letters was more convenient, people would use it more often. He pointed out that England had already adopted free city delivery and had experienced increased postal revenues as a result. An Act of Congress on March 3, 1863, effective July 1, 1863, provided that free city mail delivery be established at post offices where income from local postage was more than sufficient to pay all expenses of the service. For the first time, people mailing letters in the United States were required to put street addresses on their letters.

At the time the service began, it was limited to 49 Northern offices, which used 450 letter carriers. During the first quarter of service, New York City carriers delivered 2,069,418 letters. By June 30, 1864, free city delivery had been established in 65 cities, nationwide, with 685 carriers delivering mail in cities such as Baltimore, Boston, Brooklyn, Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit, New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Washington, D.C. In 1864, Briggs wrote Postmaster General Blair, suggesting improvements to the carrier system. Blair liked Briggs’ ideas, brought him to Washington, and appointed him special agent in charge of superintending the operation of the letter carrier system, a role he performed until his death on February 23, 1872.

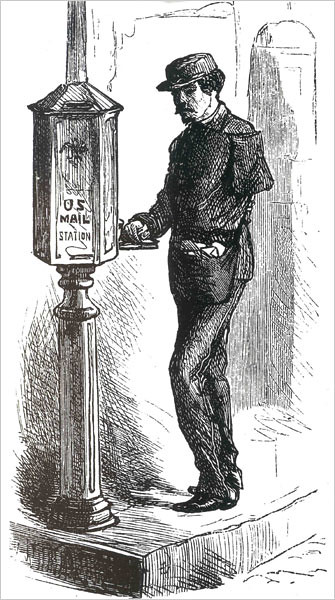

The first City Free Delivery Service letter carriers used leather satchels to carry the mail along their appointed rounds. Initially, carriers hand-delivered mail to customers. If a customer did not answer the carrier’s knock, ring, or whistle, the mail remained in the carrier’s satchel to be redelivered when the customer was home. For many years, letter carriers were required to lug as much as 70 pounds of mail matter in their leather mailbags. Before the advent of Parcel Post in 1913, carriers were compelled to load their satchels with all sorts and sizes of packages. Now, generally no packages weighing over two pounds are delivered by the carrier on foot.

By 1869 revenues from free city delivery were over ten times its cost, and the new system provided employment for many Civil War veterans as letter carriers. By 1880, 104 cities were served by 2,628 letter carriers, and by 1900, 15,322 carriers provided service to 796 cities.

Postmasters, groups of citizens, or city authorities could petition the Post Office Department for free delivery service if their city met population or postal revenue requirements. The city had to provide sidewalks and crosswalks, ensure that streets were named and lit, and assign numbers to houses.

At first, carriers were not required to wear uniforms. In his 1892 annual report to Congress, Postmaster General John Wanamaker noted that while Section 613 of the postal laws and regulations provided for a uniform for letter carriers, “good discipline requires a more strict enforcement of its provisions.”

Wanamaker was concerned that as uniforms were regulated at the discretion of postmasters, there was no general uniform throughout the country. “Each locality,” he noted, “provides its own and fixes its own price. . . As there is no regularity of time for procuring new uniforms, some of the carriers dress in worn, faded & shabby uniforms . . . it is the opinion of this office it should be made obligatory upon all carriers to furnish two uniform suits each year — one spring & summer on May 1st and one fall & winter on November 1st.”

Letter carriers’ sharp blue-grey uniforms stood out at a time when most other official uniforms (police, firemen, etc.) were dark blue in color. The uniforms purchased by carriers consisted of blue-gray sack coats, cut to extend two-thirds the distance from the hip to the knee, with matching pants.

Carriers’ hats have gone through several changes. Panama hats were introduced in 1873. Beginning in 1887, carriers sported a police-style helmet in the winter and straw hats in the summer. Straw hats appeared in the early 1890s. In 1898, a military-style hat made popular by the exploits of Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders during the Spanish-American War appeared. Bell crown caps made their appearance in 1911.

Service stars were used to signify a carrier’s length of service. After five years, one black star was worn on the uniform sleeve. For ten years, two black stars were applied and the sequence continued as service time increased. For 15 years service, one red star was worn. After 20 years, two red stars; followed by one silver star for 25 years; two silver stars after 30 years; one gold star for 35 years; two gold stars for 40 years; three gold stars for 45 years; and four gold stars for 50 years.

Carriers and other postal employees also wore badges of service. Badges were worn on hats or jackets.

By 1912, new customers were required to provide mail slots or receptacles, and postmasters were urged to encourage existing customers to provide them as well. As late as 1914, First Assistant Postmaster General Daniel C. Roper estimated that a letter carrier spent 30 minutes to an hour each day waiting at doors where there was person-to-person delivery. In 1916, efficiency experts determined that letter carriers were losing almost two hours daily waiting for patrons to come to the door. To gain back those precious hours, the Post Office Department decided that every household must have a mail box or letter slot in order to receive mail.

As early as the 1880s, the postal service had begun to encourage homeowners to attach mailboxes to their houses. In 1890, a postal commission examined 564 models and designs of household mailboxes submitted by designers and inventors. The Post Office Department request for examples had stated that the mailboxes had to meet certain standards.

- Carriers should be able to deposit mail and collect mail “without delay” from the device.

- The mailbox must be inexpensive and able to withstand bad weather, destructive pranksters, and secure the mail against thieves as best as possible.

- The mailbox must be simple enough that it does not require excessive time to open, while being “ornamental enough to please the householder.”

- The mailbox also had to be large enough to receive papers, and have some way of signaling to letter carriers that mail was in it, ready to be collected.

Not a single box of the 564 submitted fit enough of these guidelines to be approved by the postal service. Hundreds of mailbox designs were submitted for patent approval. The postal service finally agreed to accept mailboxes that fulfilled most of their requirements, but shied away from endorsing specific designs.

As of March 1, 1923, mail slots or receptacles were required for delivery service.

By the 1930s, as a convenience to customers living on the margins of a city, letter carriers began delivering to customers with “suitable boxes at the curb line.”2 In the ensuing decades American suburbanization, which exploded in the 1950s, brought an increase in curbside mailboxes. The Department introduced curbside cluster boxes in 1967. Their use has been increasingly encouraged in recent decades to promote efficiency and economy of service.

Originally, letter carriers worked 52 weeks a year, typically 9 to 11 hours a day from Monday through Saturday, and if necessary, part of Sunday. An Act of June 27, 1884, granted them 15 days of leave per year. In 1888, Congress declared that 8 hours was a full day’s work and that carriers would be paid for additional hours worked per day. The 40-hour work week began in 1935.

Letter carriers were the first postal workers to form their own union. They had tried to organize a national union at least three times—in 1870 in Washington, DC, in 1877 in New York City, and in 1880 again in New York City. Recognizing that these earlier attempts had failed in part due to the expense of regularly convening enough carriers to sustain a national organization, in 1889, the Milwaukee Letter Carriers Association decided to time their call for another national meeting of carriers to coincide with the annual reunion of the Grand Army of the Republic — an organization of Union Army veterans — so that letter carriers who were veterans could take advantage of reduced train fares.

On August 29, 1889, delegates moved quickly, unanimously adopting a resolution to form a National Association of Letter Carriers (NALC). On the next day, August 30, 1889, they elected William Wood of Detroit as the first president and appointed an Executive Board to coordinate all legislative efforts. NALC had 52 locals, called branches, with 4,600 members in 1890, and 335 branches by 1892.

In the beginning, the union focused on forcing postmasters to honor federal law mandating an eight-hour day for federal employees. In 1893, the NALC won a Supreme Court decision and $3.5 million in back overtime pay. Local postmasters vigorously opposed the union, even though it did not sponsor strikes. Today, the NALC has 2,500 local branches representing letter carriers in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands and Guam.

Carriers walked as many as 22 miles a day, carrying up to 50 pounds of mail at a time. They were instructed to deliver letters frequently and promptly — generally twice a day to homes and up to four times a day to businesses. The second residential delivery was discontinued on April 17, 1950, in most cities. Multiple deliveries to businesses were phased out over the next few decades as changing transportation patterns made most mail available for first-trip delivery. The weight limit of a carrier’s load was reduced to 35 pounds by the mid-1950s and remains the same today.

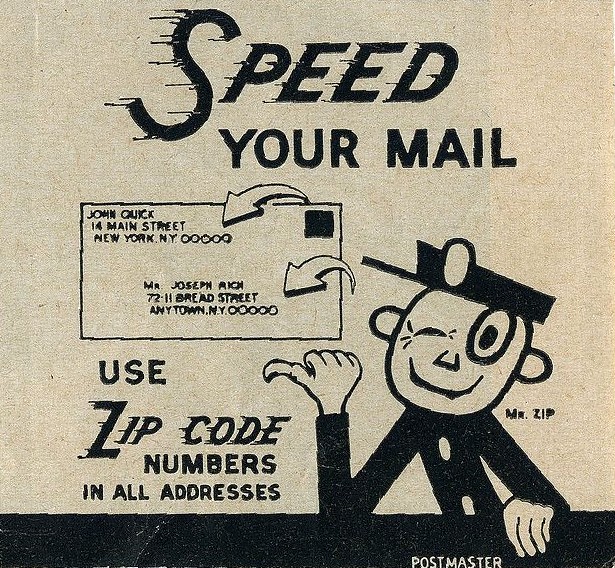

On July 1, 1963, non-mandatory five-digit ZIP Codes were introduced nationwide. ZIP is an acronym for Zone Improvement Plan, named to suggest that the mail travels more efficiently and quickly (zipping along) when senders use the code in the postal address.. The first three digits of this postal code describe the sectional center facility (SCF) or “sec center,” a central mail processing facility with those three digits. The fourth and fifth digits give a more precise locale within the SCF[6]. The SCF sorts mail to all post offices with those first three digits in their ZIP Codes. The mail is sorted according to the final two digits of the ZIP Code and sent to the corresponding post offices in the early morning. Sectional centers do not deliver mail and are not open to the public (though the building may include a post office open to the public), and most of their employees work night shift. Mail picked up at post offices is sent to their own SCF in the afternoon, where the mail is sorted overnight. In the cases of large cities, the last two digits coincide with the older postal zone number.

The USPOD issued its Publication 59: Abbreviations for Use with ZIP Code on October 1, 1963, with a list of two-letter state abbreviations which are generally written with both letters capitalized. In 1967, ZIP Codes became mandatory for second and third-class bulk mailers, and the system was soon adopted generally. The United States Post Office used a cartoon character which it called Mr. ZIP to promote the use of the ZIP Code. He was often depicted with a legend such as “USE ZIP CODE” in the selvage of panes of postage stamps or on the covers of booklet panes of stamps.

In 1983, the U.S. Postal Service introduced an expanded ZIP Code system that it called ZIP+4, often called “plus-four codes”, “add-on codes”, or “add-ons”. A ZIP+4 Code uses the basic five-digit code plus four additional digits to identify a geographic segment within the five-digit delivery area, such as a city block, a group of apartments, an individual high-volume receiver of mail, a post office box, or any other unit that could use an extra identifier to aid in efficient mail sorting and delivery. However, initial attempts to promote universal use of the new format met with public resistance and today the plus-four code is not required. In general, mail is read by a multiline optical character reader (MLOCR) that almost instantly determines the correct ZIP+4 Code from the address—along with the even more specific delivery point—and sprays an Intelligent Mail barcode (IM) on the face of the mail piece that corresponds to 11 digits—nine for the ZIP+4 Code and two for the delivery point.

City Delivery mail satchel

In 1973, the United States Postal Service decided to replace the carriers’ leather satchels with canvas ones. Although the traditional leather satchels are twice as heavy (3-4 pounds) as canvas bags, carriers were reluctant to make the switch. Leather certainly held up well to the demands of mail delivery and many of the satchels survived six or more years of service. Most carriers, in fact, sought out old, yet functioning replacement leather mailbags rather than use the new canvas satchels.

The canvas bags, which were not as sturdy, wore out in less than two years, and certainly were no match for leather bags when it came to fending off dogs along the route. Even the sturdiest leather bags wore out after time. Eventually, only canvas bags were available as replacements and carriers had no choice but to switch. By the late 1980s, almost all carriers were using canvas bags.

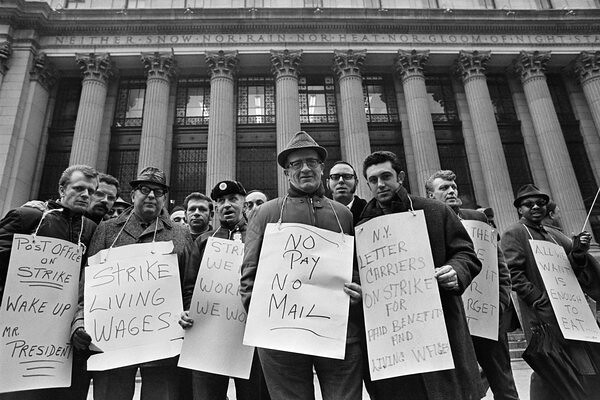

Letter carrier morale plummeted during the mid-1960s as inflation eroded carriers’ salaries. A growing sense of militancy developed as carriers and their families in big cities neared the poverty level.

In New York City’s Branch 36, a storm of protest erupted when President Richard Nixon provided only a 4.1 percent pay raise in 1969, a figure the NALC deemed unacceptable. Events escalated as the Christmas mail rush neared and Nixon called NALC President James Rademacher to the White House to forge a compromise that tied a pay raise in 1970 to the concept of an independent postal authority to bargain with postal unions The Nixon-Rademacher agreement incensed letter carriers and when a House committee the following March approved a bill reflecting the Nixon-Rademacher compromise, calls for a strike were shouted in New York’s Branch 36 and other branches.

Despite being barred from participating in a strike, on March 17, 1970, the votes were counted in Branch 36, and a long-threatened strike was approved, 1,555 to 1,055. At 12:01 a.m. on March 18, picket lines created by Branch 36 went up at post offices throughout Manhattan and the Bronx in New York City as letter carriers went on strike. Within two days, more than 200,000 letter carriers and other postal employees across the country had joined the walkout. This was the first strike in the postal service’s nearly 200-year-long history and the largest ever walkout by Federal employees in the United States.

Nixon called out 25,000 soldiers to move the mail in New York City. The strike ended after eight days when local NALC leaders assured strikers that an agreement had been reached, even though their word was premature. Round-the-clock negotiations began and on April 2 a satisfactory agreement was reached, which was quickly approved by Congress.

Today, city letter carriers are paid hourly with the potential for overtime. Letter Carriers are also subject to “pivoting” on a daily basis. Pivoting (when a carrier’s assigned route will take less than 8 hours to complete, management may “pivot” said carrier to work on another route to fill that carrier up to 8 hours.) is a tool postal management uses to redistribute and eliminate overtime costs, based on consultation with the carrier about his/her estimated workload for the day and mail volume projections from the DOIS (Delivery Operations Information System) computer program. Routes are adjusted and/ or eliminated based on information (length, time, and overall workload) also controlled by this program, consultations with the carrier assigned to the route, and a current PS Form 3999 (street observation by a postal supervisor to determine accurate times spent on actual delivery of mail). Many carriers object to the fact that average mail volumes used for route adjustments come from DOIS as it is not an actual count of the mail by a person and instead by a machine, leading carriers to question the accuracy of the count.

Letter carriers typically work urban routes that are high density and low mileage. These routes are classified as either “mounted” routes (for those that require a vehicle) or “walking” routes (for those that are done on foot). When working a mounted route, letter carriers usually drive distinctive white vans with the logo of the United States Postal Service on the side and deliver to curbside and building affixed mailboxes. Carriers who walk generally also drive postal vehicles to their routes, park at a specified location, and carry one “loop” of mail, up one side of the street and back down the other side, until they are back to their vehicle. This method of delivery is referred to as “park and loop”. Letter carriers may also accommodate alternate delivery points in cases where “extreme physical hardship” is confirmed.

Women have been transporting mail in the United States since the late 1800s. According to the Post Office Department’s archives, “the first known appointment of a woman to carry mail was on April 3, 1845, when Postmaster General Cave Johnson appointed Sarah Black to carry the mail between Charlestown Md P.O. & the Rail Road . . . daily or as often as requisite at $48 per annum. For at least two years Black served as a mail messenger, ferrying the mail between Charlestown’s train depot and its Post Office.”

At least two women, Susanna A. Brunner in New York and Minnie Westman in Oregon, were known to be mail carriers in the 1880s. Mary Fields, nicknamed “Stagecoach Mary”, was the first black woman to work for the USPS, driving a stagecoach in Montana from 1895 until the early 1900s. When aviation introduced airmail, the first woman mail pilot was Katherine Stinson who dropped mailbags from her plane at the Montana State Fair in September 1913.

The first women city carriers were appointed in World War I and by 2007, about 59,700 women served as city carriers and 36,600 as rural carriers representing 40% of the carrier force. In 2006, 224,400 letter carriers delivered mail in the nation’s cities.

Each year on the second Saturday in May, as they deliver the mail, letter carriers collect non-perishable food donations left by the mailboxes on their route from postal customers participating in the NALC Stamp Out Hunger Food Drive. It is considered the largest one-day food collection effort in the United States. Participation is strictly voluntary.

The national, coordinated effort by the NALC grew out of discussions in 1991 by a number of leaders at the time, including NALC President Vincent Sombrotto, AFL-CIO Community Services Director Joseph Velasquez and USPS Postmaster General Anthony Frank. A pilot drive was held in 10 cities in October 1991, and it proved so successful that work began immediately on making it a nationwide effort. Input from food banks and pantries suggested that late spring would be the best time since by then most food banks in the country start running out of donations received during the Thanksgiving and Christmas holiday periods.

In 2014, the drive gathered 72.5 million pounds of food, the 11th consecutive year the drive surpassed 70 million pounds. That year’s results brought the total to more than 1.3 billion pounds since the national drive began in 1992. The Stamp Out Hunger Food Drive has also received two Presidential Certificates of Achievement.

A 1921 postal committee charged with determining who should be credited with the establishment of free city delivery, after examining the available evidence, reported to Postmaster General Will Hays that “no one individual can be considered the author or originator of this service …” The committee said, “Mr. Briggs cannot be properly credited as the author of the City Free Delivery Service, but the evidence seems sufficient to warrant the statement that he was the first letter carrier in the city of Cleveland, Ohio.”

A plaque in the Cleveland Post Office commemorates Briggs’ service as that city’s first free letter carrier and his contributions to establishing the service nationwide.

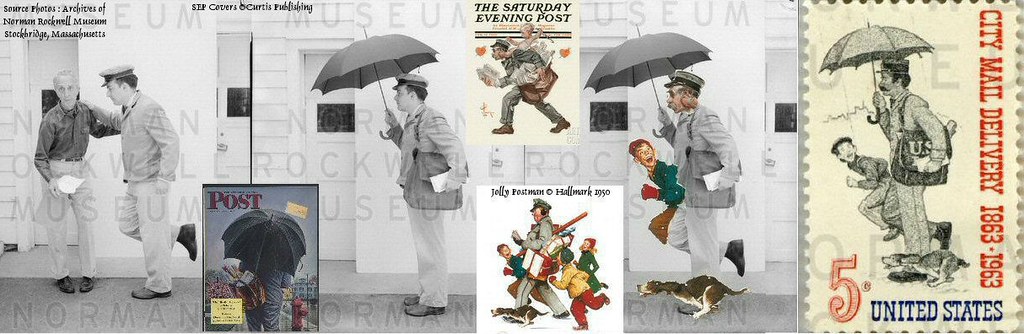

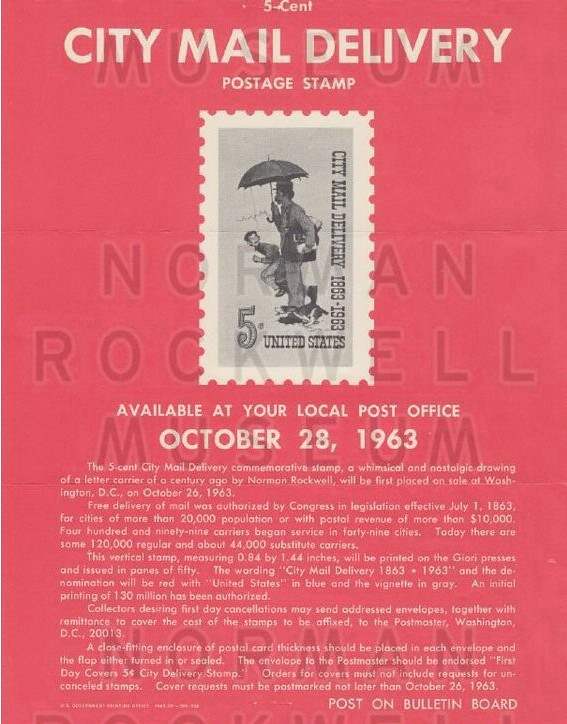

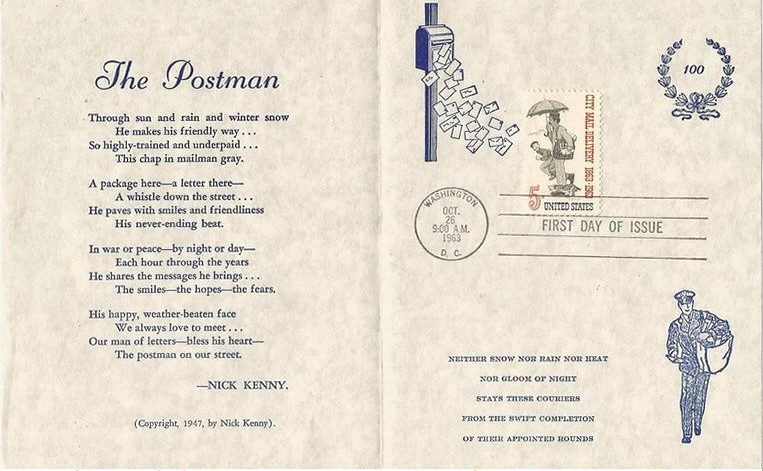

A single 5-cent City Mail Delivery commemorative stamp was issued through the Washington, DC, post office on October 26, 1963 (Scott #1238). Norman Rockwell’s design is a whimsical and nostalgic drawing of a Civil War-era letter carrier. A retired banker from Stockbridge, Massachusetts — William James Roy — was Rockwell’s model for the painting. The wording CITY MAIL DELIVERY 1863-1963 and the denomination are in red with UNITED STATES in dark blue and the vignette in gray.

The stamp was printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing on the Giori press and issued in panes of fifty stamps each, perforated 11. An initial printing of 130 million stamps was authorized with a total of 128,450,000 actually issued.

I started this little blog called A Stamp A Day on July 1, 2016, as a way to write about the different stamp-issuing entities that I had represented in my collection. I covered those more or less alphabetically with the entries originally intended to be (very) brief bits of key facts about the various nations, colonies, organizations, military units, etc. that released postage stamps. Commemoration of event anniversaries and holidays were included on rare occasions.

Over the course of 734 entries, lengthy outweighs brevity and a stamp issuer is only highlighted once I’ve added a new one to my collection (although I do make exceptions). The majority of articles in mid-2018 deal with anniversaries or holidays as well as “random stamp days” on which I just pick a stamp that appeals to me and write about whatever it pictures. While there have been minor frustrations along the way (slow Internet being the predominant reason — rain during the monsoon season and heat during the remainder of the year tends to create unexpected outages), it has still been a labor of love over the course of these 24 months. I have every reason that I will be able to persevere for the foreseeable future. I hope you all enjoy learning something (perhaps a lot) each and every day as I have….

Are any of these stamps currently available for purchase?

LikeLike