On April 29, 1945, Führer and Reich Chancellor (Reichskanzler) of the German Third Reich Adolf Hitler married his longtime partner Eva Anna Paula Braun in the Führerbunker air raid shelter in Berlin. Designating Admiral Karl Dönitz as his successor, on the following day Hitler killed himself by gunshot while Braun committed suicide with him by taking cyanide. In accordance with Hitler’s prior written and verbal instructions, that afternoon their remains were carried up the stairs through the bunker’s emergency exit, doused in petrol, and set alight in the Reich Chancellery garden outside the bunker. Records in the Soviet archives show that their burnt remains were recovered and interred in successive locations until 1970, when they were again exhumed, cremated, and the ashes scattered. Hitler had taken up residence in the Führerbunker on January 16, 1945, and it became the center of the Nazi regime until the last week of World War II in Europe. The Soviet forces captured the Reich Chancellery on May 2, 1945, entering the bunker complex at 09:00 that morning.

Eva Braun was born on February 6, 1912, in Munich, Bavaria, the second daughter of school teacher Friedrich “Fritz” Braun and Franziska “Fanny” Kronberger. Her mother had worked as a seamstress before her marriage. She had an elder sister, Ilse, and a younger sister, Margarete (Gretl). Braun’s parents were divorced in April 1921, but remarried in November 1922, probably for financial reasons (hyperinflation was plaguing the German economy at the time).

Braun was educated at a Catholic lyceum in Munich, and then for one year at a business school in the Convent of the English Sisters in Simbach am Inn, where she had average grades and a talent for athletics. At age 17, she took a job working for Heinrich Hoffmann, the official photographer for the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, abbreviated NSDAP and commonly referred to in English as the Nazi Party). Initially employed as a shop assistant and sales clerk, she soon learned how to use a camera and develop photos. She met Hitler, 23 years her senior, at Hoffmann’s studio in Munich in October 1929. He had been introduced to her as “Herr Wolff”. Eva’s sister, Gretl, also worked for Hoffman from 1932 onward, and the women rented an apartment together for a time. Gretl accompanied her sister on her later trips with Hitler to the Obersalzberg, a mountainside retreat situated above the market town of Berchtesgaden in Bavaria. Located about 75 miles (120 kilometers) southeast of Munich, close to the border with Austria, it is best known as the site of Adolf Hitler’s former mountain residence, the Berghof, and of the mountaintop Kehlsteinhaus, popularly known in the English-speaking world as the “Eagle’s Nest”.

Hitler lived with his half-niece, Geli Raubal, in an apartment at Prinzregentenplatz 16 in Munich from 1929 until her death. On September 18, 1931, Raubal was found dead in the apartment with a gunshot wound, an apparent suicide with Hitler’s pistol. Hitler was in Nuremberg at the time. The relationship — likely the most intense of his life — had been important to him. Hitler began seeing more of Braun after Raubal’s suicide.

Braun herself attempted suicide on August 10 or 11, 1932, by shooting herself in the chest with her father’s pistol. Historians feel the attempt was not serious, but was a bid for Hitler’s attention. After Braun’s recovery, Hitler became more committed to her and by the end of 1932 they had become lovers. She often stayed overnight at his Munich apartment when he was in town. Beginning in 1933, Braun worked as a photographer for Hoffmann. This position enabled her to travel — accompanied by Hoffmann — with Hitler’s entourage as a photographer for the Nazi Party. Later in her career, she worked for Hoffman’s art press.

In 1933, Hitler purchased a small holiday home on the mountain at Obersalzberg. Renovations began in 1934 and were completed by 1936. A large wing was added onto the original house and several additional buildings were constructed. The entire area was fenced off, and remaining houses on the mountain were purchased by the Nazi Party and demolished. Braun and the other members of the entourage were cut off from the outside world when in residence. Speer, Hermann Göring, and Martin Bormann had houses constructed inside the compound.

Hitler’s valet, Heinz Linge, stated in his memoirs that Hitler and Braun had two bedrooms and two bathrooms with interconnecting doors at the Berghof, and Hitler would end most evenings alone with her in his study before they retired to bed. She would wear a “dressing gown or house-coat” and drink wine; Hitler would have tea. Public displays of affection or physical contact were nonexistent, even in the enclosed world of the Berghof. Braun took the role of hostess amongst the regular visitors, though she was not involved in running the household. She regularly invited friends and family members to accompany her during her stays, the only guest to do so.

According to a fragment of her diary and the account of biographer Nerin Gun, Braun’s second suicide attempt occurred in May 1935. She took an overdose of sleeping pills when Hitler failed to make time for her in his life. Hitler provided Eva and her sister with a three-bedroom apartment in Munich that August, and the next year the sisters were provided with a villa in Bogenhausen at Wasserburgerstr. 12 (now Delpstr. 12). By 1936, Braun was at Hitler’s household at the Berghof near Berchtesgaden whenever he was in residence there, but she lived mostly in Munich. Braun also had her own apartment at the new Reich Chancellery in Berlin, completed to a design by Albert Speer.

Braun was a member of Hoffman’s staff when she attended the Nuremberg Rally for the first time in 1935. Hitler’s half-sister, Angela Raubal (the dead Geli’s mother), took exception to her presence there, and was later dismissed from her position as housekeeper at his house in Berchtesgaden. Researchers are unable to ascertain if her dislike for Braun was the only reason for her departure, but other members of Hitler’s entourage saw Braun as untouchable from then on.

Hitler wished to present himself in the image of a chaste hero; in the Nazi ideology, men were the political leaders and warriors, and women were homemakers. He believed that he was sexually attractive to women and wished to exploit this for political gain by remaining single, as he felt marriage would decrease his appeal. He and Braun never appeared as a couple in public; the only time they appeared together in a published news photo was when she sat near him at the 1936 Winter Olympics. The German people were unaware of Braun’s relationship with Hitler until after the war. According to Speer’s memoirs, Braun never slept in the same room as Hitler and had her own rooms at the Berghof, in Hitler’s Berlin residence, and in the Berlin bunker. Speer later said, “Eva Braun will prove a great disappointment to historians.”

Biographer Heike Görtemaker noted that women did not play a big role in the politics of the Third Reich. Braun’s political influence on Hitler was apparently minimal. She was never allowed to stay in the room when business or political conversations took place, and was sent out of the room when cabinet ministers or other dignitaries were present. She was not a member of the Nazi Party. In his post-war memoirs, Hoffmann characterized Braun’s outlook as “inconsequential and feather-brained”; her main interests were sports, clothes, and the cinema. By all accounts, she led a sheltered and privileged existence and seemed uninterested in politics. One instance when she took an interest was in 1943, shortly after Germany had fully transitioned to a total war economy. Among other things, this meant a potential ban on women’s cosmetics and luxuries. According to Speer’s memoirs, Braun approached Hitler in “high indignation”; Hitler quietly instructed Speer, who was armaments minister at the time, to halt production of women’s cosmetics and luxuries rather than instituting an outright ban.

Braun continued to work for Hoffmann after commencing her relationship with Hitler. She took many photographs and movies of members of the inner circle, and some of these were sold to Hoffmann for extremely high prices. She received money from Hoffmann’s company as late as 1943, and also held the position of private secretary to Hitler. This guise meant she could enter and leave the Chancellery unremarked, though she used a side entrance and a rear staircase. Görtemaker notes that Braun and Hitler enjoyed a normal sex life. Braun’s friends and relatives described Eva giggling over a 1938 photograph of Neville Chamberlain sitting on a sofa in Hitler’s Munich flat with the remark: “If only he knew what goings-on that sofa has seen.”

On June 3, 1944, Braun’s sister Gretl Braun married SS-Gruppenführer Hermann Fegelein, who served as Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler’s liaison officer on Hitler’s staff. Hitler used the marriage as an excuse to allow Braun to appear at official functions, as she could then be introduced as Fegelein’s sister-in-law. When Fegelein was caught in the closing days of the war trying to escape to Sweden or Switzerland, Hitler ordered his execution. He was shot for desertion in the garden of the Reich Chancellery on April 28, 1945.

When Henriette von Schirach suggested that Braun should go into hiding after the war, Braun replied, “Do you think I would let him die alone? I will stay with him up until the last moment …” Hitler named Braun in his will, to receive 12,000 Reichsmarks yearly after his death. He was very fond of her, and worried when she participated in sports or was late returning for tea.

Braun was very fond of Negus and Stasi, her two Scottish Terrier dogs, and they appear in her home movies. She usually kept them away from Hitler’s German Shepherd, Blondi. Blondi was killed by one of the entourage on April 29, 1945 when Hitler ordered that one of the cyanide capsules obtained for Braun and Hitler’s suicide the next day be tested on the dog. Braun’s dogs and Blondi’s puppies were shot on April 30 by Hitler’s dog handler, Fritz Tornow.

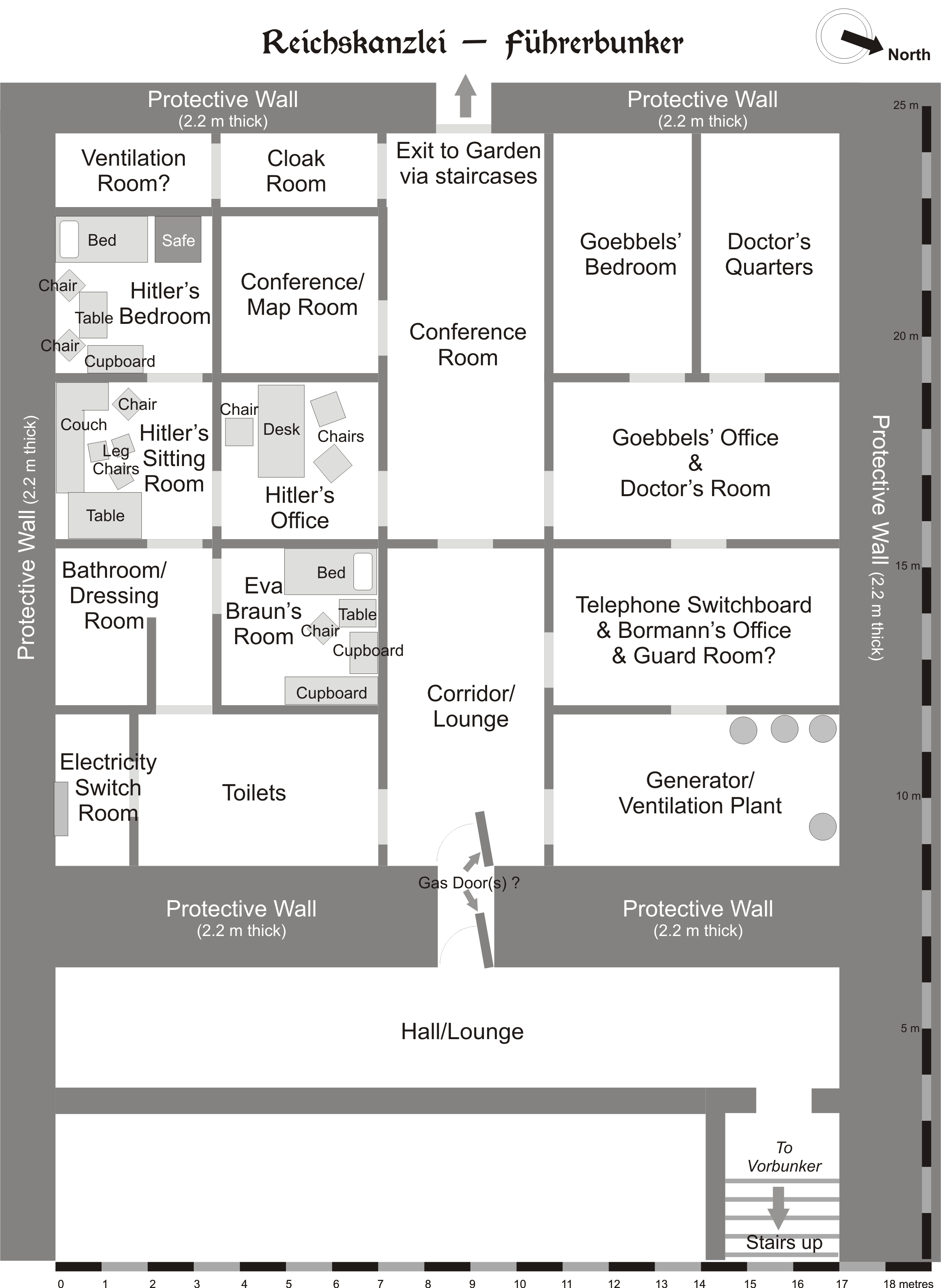

The Reich Chancellery bunker was initially constructed as a temporary air-raid shelter for Hitler who actually spent very little time in the capital during most of the war. Increased bombing of Berlin led to expansion of the complex as an improvised permanent shelter. The elaborate complex consisted of two separate shelters, the Vorbunker (“forward bunker”; the upper bunker), completed in 1936, and the Führerbunker, located 8.2 feet (2.5 meters) lower than the Vorbunker and to the west-southwest, completed in 1944. They were connected by a stairway set at right angles and could be closed off from each other by a bulkhead and steel door. The Vorbunker was located 4.9 feet (1.5 meters) beneath the cellar of a large reception hall behind the old Reich Chancellery at Wilhelmstrasse 77. The Führerbunker was located about 28 feet (8.5 meters) beneath the garden of the old Reich Chancellery, 300 feet (120 meters) north of the new Reich Chancellery building at Voßstraße 6. Besides being deeper under ground, the Führerbunker had significantly more reinforcement. Its roof was made of concrete almost 9.8 feet (3 meters) thick. About 30 small rooms were protected by approximately 13 feet (4 meters) of concrete; exits led into the main buildings, as well as an emergency exit up to the garden. The Führerbunker development was built by the Hochtief company as part of an extensive program of subterranean construction in Berlin begun in 1940.

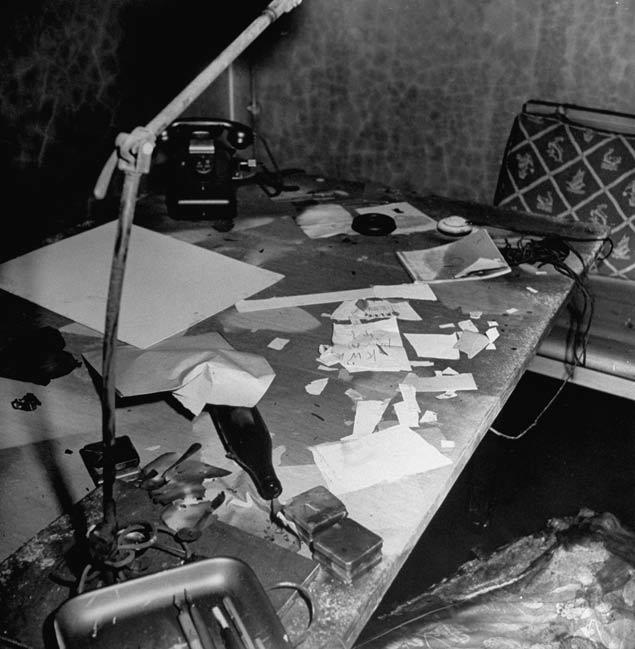

Hitler’s accommodations were in this newer, lower section, and by February 1945 it had been decorated with high-quality furniture taken from the Chancellery, along with several framed oil paintings. After descending the stairs into the lower section and passing through the steel door, there was a long corridor with a series of rooms on each side. On the right side were a series of rooms which included generator/ventilation rooms and the telephone switchboard. On the left side was Eva Braun’s bedroom/sitting room (also known as Hitler’s private guest room), an ante-chamber (also known as Hitler’s sitting room), which led into Hitler’s study/office. On the wall hung a large portrait of Frederick the Great, one of Hitler’s heroes. A door led into Hitler’s modestly furnished bedroom. Next to it was the conference/map room (also known as the briefing/situation room) which had a door that led out into the waiting room/ante-room.

The bunker complex was self-contained. However, as the Führerbunker was below the water table, conditions were unpleasantly damp, with pumps running continuously to remove groundwater. A diesel generator provided electricity, and well water was pumped in as the water supply. Communications systems included a telex, a telephone switchboard, and an army radio set with an outdoor antenna. As conditions deteriorated at the end of the war, Hitler received much of his war news from BBC radio broadcasts and via courier.

Hitler moved into the Führerbunker on January 16, 1945, joined by his senior staff, including Martin Bormann. In early April, Braun travelled from Munich to Berlin to be with Hitler at the bunker, refusing to leave as the Red Army closed in on the capital. Joseph Goebbels joined them in April, while Magda Goebbels and their six children took residence in the upper Vorbunker. Two or three dozen support, medical, and administrative staff were also sheltered there. These included Hitler’s secretaries (including Traudl Junge), a nurse named Erna Flegel, and telephone switchboard operator Sergeant Rochus Misch. Initially, Hitler continued to utilize the undamaged wing of the Reich Chancellery, where he held afternoon military conferences in his large study. Afterwards, he would have tea with his secretaries before going back down into the bunker complex for the night. After several weeks of this routine, he seldom left the bunker except for short strolls in the chancellery garden with his dog Blondi. The bunker was crowded, the atmosphere was oppressive, and air raids occurred daily. Hitler mostly stayed on the lower level, where it was quieter and he could sleep. Conferences took place for much of the night, often until 05:00.

On April 16, the Red Army started the Battle of Berlin, and they started to encircle the city by April 19. Hitler made his last trip to the surface on April 20, his 56th birthday, going to the ruined garden of the Reich Chancellery where he awarded the Iron Cross to boy soldiers of the Hitler Youth. That afternoon, Berlin was bombarded by Soviet artillery for the first time.

Hitler was in denial about the dire situation and placed his hopes on the units commanded by Waffen-SS General Felix Steiner, the Armeeabteilung Steiner (Army Detachment Steiner). On April 21, Hitler ordered Steiner to attack the northern flank of the encircling Soviet salient and ordered the German Ninth Army, south-east of Berlin, to attack northward in a pincer attack. That evening, Red Army tanks reached the outskirts of Berlin. Hitler was told at his afternoon situation conference on April 22 that Steiner’s forces had not moved, and he fell into a tearful rage when he realized that the attack was not going to be carried out. He openly declared for the first time the war was lost — and he blamed his generals. Hitler announced that he would stay in Berlin until the end and then shoot himself.

On April 23, Hitler appointed General of the Artillery Helmuth Weidling, commander of the LVI Panzer Corps, as the commander of the Berlin Defense Area, replacing Lieutenant-Colonel (Oberstleutnant) Ernst Kaether. The Red Army had consolidated their investment of Berlin by April 25, despite the commands being issued from the Führerbunker. There was no prospect that the German defense could do anything, but delay the city’s capture. Hitler summoned Field Marshal Robert Ritter von Greim from Munich to Berlin to take over command of the Luftwaffe from Hermann Göring, and he arrived on April 26 along with his mistress and crack test pilot Hanna Reitsch.

On April 28, Hitler learned that Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler was trying to discuss surrender terms with the Western Allies through Count Folke Bernadotte, and Hitler considered this treason. Enraged, he ordered Himmler’s arrest and had Hermann Fegelein shot, who was Himmler’s SS representative at Hitler’s HQ in Berlin. On the same day, General Hans Krebs made his last telephone call from the Führerbunker to Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, Chief of German Armed Forces High Command (OKW) in Fürstenberg. Krebs told him that all would be lost if relief did not arrive within 48 hours. Keitel promised to exert the utmost pressure on Generals Walther Wenck, commander of the Twelfth Army, and Theodor Busse, commander of the Ninth Army. Meanwhile, Hitler’s private secretary Martin Bormann wired to German Admiral Karl Dönitz: “Reich Chancellery a heap of rubble.” He said that the foreign press was reporting fresh acts of treason and “that without exception Schörner, Wenck and the others must give evidence of their loyalty by the quickest relief of the Führer”.

That evening, von Greim and Reitsch flew out from Berlin in an Arado Ar 96 trainer. Field Marshal von Greim was ordered to get the Luftwaffe to attack the Soviet forces that had just reached Potsdamerplatz, only a city block from the Führerbunker. During the night of April 28, General Wenck reported to Keitel that his Twelfth Army had been forced back along the entire front and it was no longer possible for his army to relieve Berlin. Keitel gave Wenck permission to break off the attempt. Later that night, news was received that there had been an uprising in northern Italy, that his ally Benito Mussolini had been captured by the Partisans and that armistice negotiations were being initiated by commanders in Italy. There was also the news of an attempted coup in Munich. By this time, Russian forces were only some 1,000 yards from the bunker.

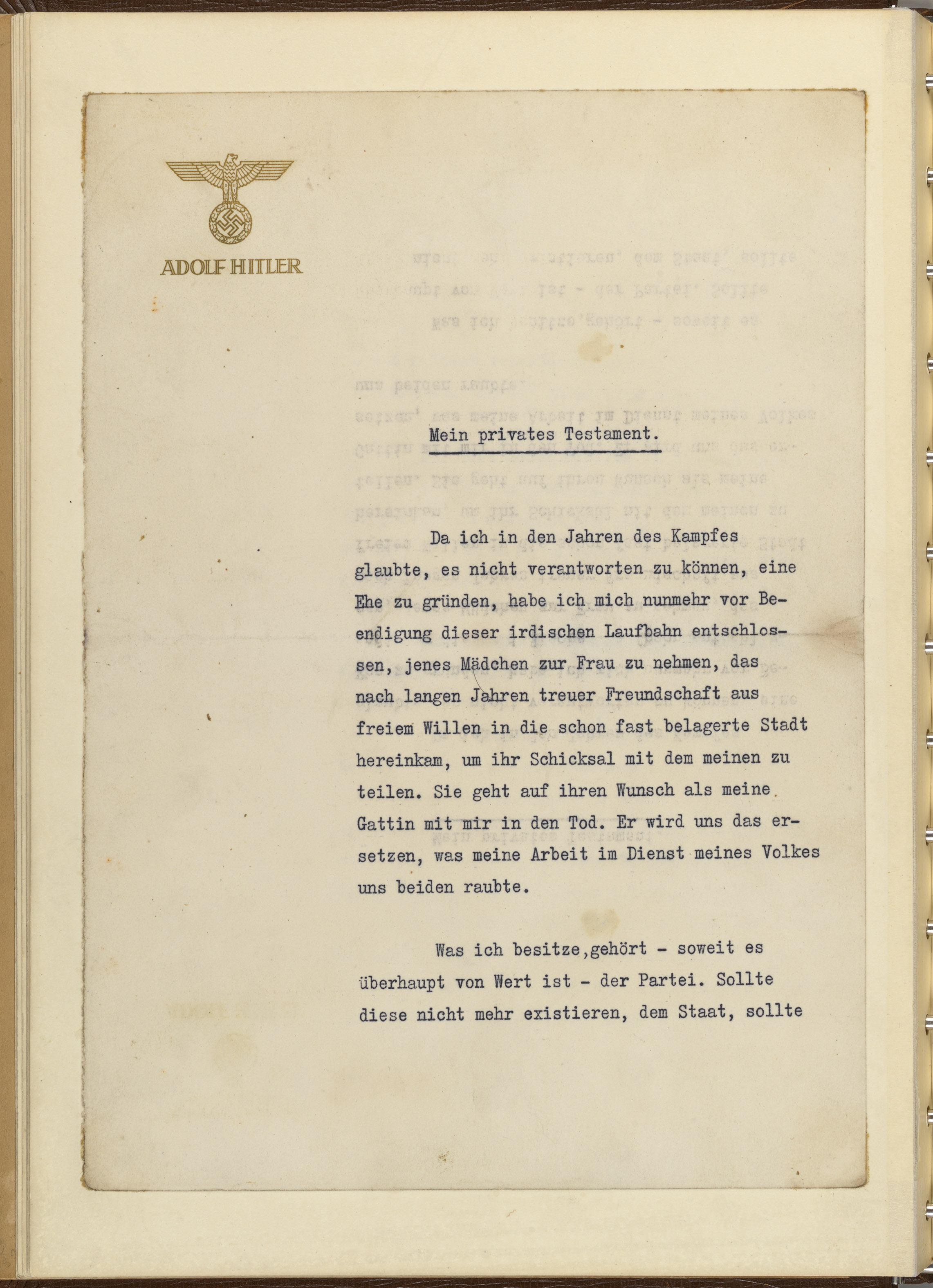

Hitler knew that he soon would have to commit suicide to avoid the humiliation of capture and trial. Before doing so, he desired to marry his long-time mistress Eva Braun and write his final political testament and personal will.

Sometime around 11:30 on the night of April 28, Hitler’s secretary — 25-year-old Gertrude Junge — awoke from a nap and entered Hitler’s study. Hitler approached, shook her hand and asked “‘Have you had a nice little rest, child?’” Junge replied “Yes, I have slept a little.” Thereupon he said, “Come along, I want to dictate something.”

They went into the little map, or conference, room near Hitler’s quarters. She was about to remove the cover from the typewriter, as Hitler normally dictated directly to the typewriter, when Hitler said “Take it down on the shorthand pad.” She sat down alone at the big table and waited. Hitler stood in his usual place by the broad side of the table, leaned both hands on it, and stared at the empty table top, no longer covered that day with maps. For several seconds Hitler did not say anything. Then, suddenly he began to speak the first words: “My political testament.”

After finishing his political testament, according to Junge, Hitler paused a brief moment and then began dictating his private will. Hitler’s personal will was shorter. It explained his marriage, disposed of his property, and announced his impending death.

The dictation was completed. Hitler had not made any corrections on either document. He moved away from the table on which he had been leaning all this time, and “suddenly there is an exhausted, hunted expression in his eyes.” Hitler said, “Type that out for me at once in triplicate and then bring it in to me.” Junge felt that there was something urgent in his voice, and thought the most important, most crucial document written by Hitler was to go out into the world without any corrections or thorough revision.

After Junge departed the conference room to type up the documents, guests began entering to attend the wedding ceremony. In the meantime Hitler was in his sitting room with a few people, trying to get the wedding ready in a dignified way, while the conference room was turned into a registry office and set up for the ceremony. SS-Major Heinz Linge (Hitler’s valet since 1935) began getting things ready for the post-wedding ceremony, including gathering up food and drink for Hitler’s inner circle.

Josef Goebbels, in his capacity of Gauleiter of Berlin, knew of someone authorized to act as a registrar of marriage who was still in Berlin, fighting with the Volkssturm — 50-year-old municipal councilor Walter Wagner. A group of SS men was dispatched across the city to bring him back. Wagner appeared shortly before 01:00 on April 29 in the uniform of the Nazi Party and the arm-band of the Volkssturm.

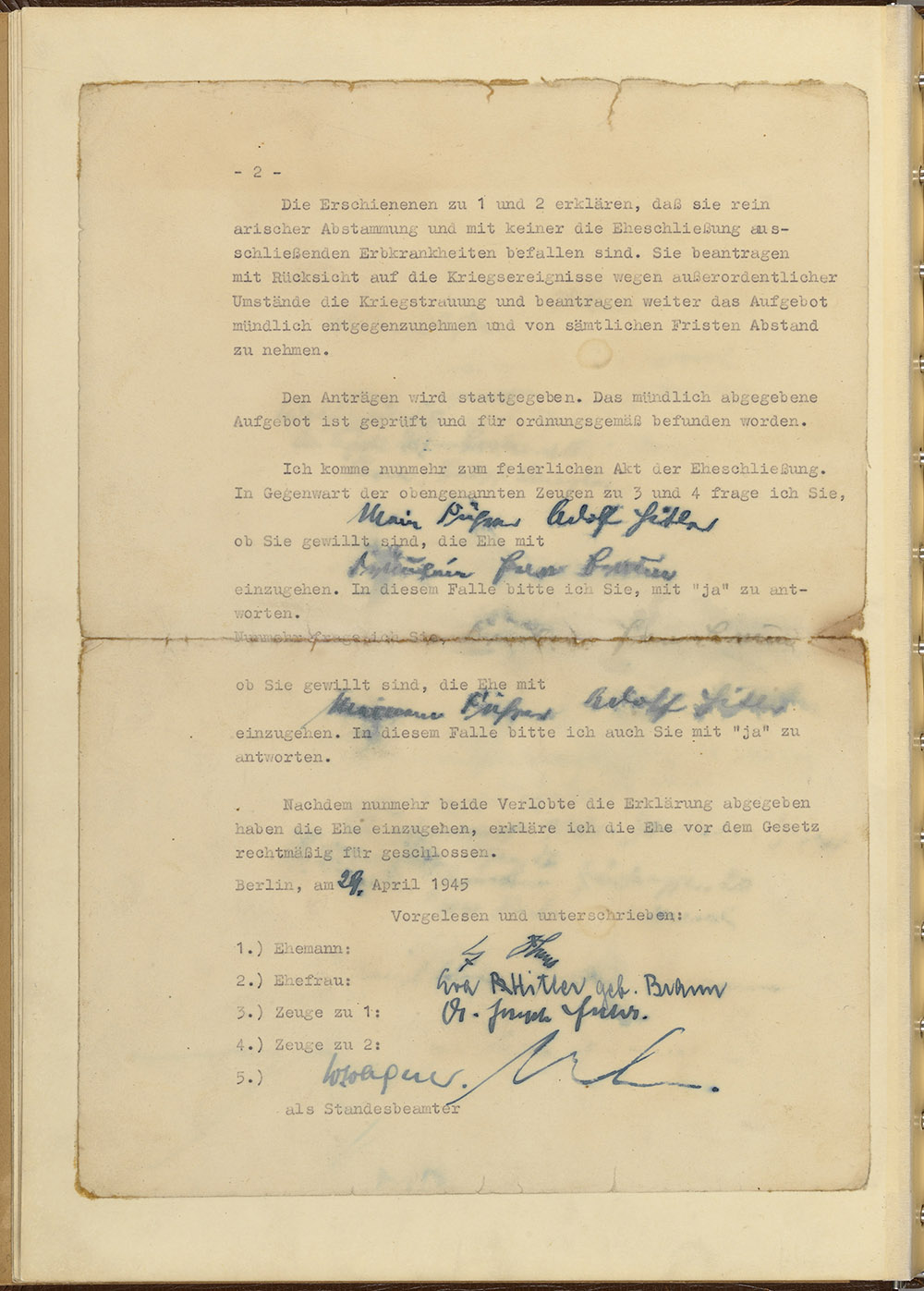

The ceremony took place in the small conference room or map room, probably at some point between 01:00 and 02:00. Hitler and Braun left their apartment hand in hand and went into the conference room. Hitler’s face was ashen, his gaze wandered restlessly. Eva Braun was also pale from sleepless nights. Joseph Goebbels and Martin Bormann were waiting for them in the antechamber. In the conference room, the party greeted Walter Wagner who had taken up his position at the table. Then they sat down in the first two chairs, and Bormann and Goebbels too went to their assigned places. The door was closed. The two parties declared that they were of pure Aryan descent and were free from hereditary disease. In a few minutes, the parties had given assent, the register had been signed and the ceremony was over. When the bride came to sign her name on the marriage certificate she began to write “Eva Braun,” but quickly struck out the initial letter B, and corrected it to Hitler. Bormann and Goebbels and Wagner also signed the register as witnesses. The ceremony lasted no longer than ten minutes.

Bormann opened the door again when Hitler and Eva were signing the license. Hitler then kissed Eva’s hand. They went into the conference passage where they shook hands with those waiting. They then withdrew into their private apartments for a wedding breakfast. Shortly afterwards, Bormann, Goebbels, Frau Goebbels, and Hitler’s two secretaries, Frau Gerda Christian and Frau Junge, were invited into the private suite. Junge would not come right away as she was typing across the hall. Wagner lingered for some 20 minutes at the reception. He munched a liverwurst sandwich, had one or two glasses of champagne, chatted with the bride, and headed back to the front lines.

For part of the time General of Infantry Hans Krebs, Lt. Gen. Wilhelm Burgdorf, and Lt. Col. Nicholaus von Below (Hitler’s Luftwaffe Adjutant since 1937) came in and joined the party, as did Werner Naumann (State Secretary in Ministry of Propaganda since 1944), Arthur Axmann (Reich Youth Leader since 1940), Ambassador Walter Hewel (permanent representative of Foreign Ministry to Hitler at Fuehrer headquarters since 1940), Heinz Linge (Hitler’s valet), SS-Major Otto Guensche (personal adjutant to Hitler), and Fraulein Manzialy, the vegetarian cook. There they sat for hours, drinking champagne and tea, eating sandwiches, and talking. Hitler spoke again of his plans of suicide and expressed his belief that National Socialism was finished and would never revive (or would not resurrect so soon again), and that death would be a relief to him now that he had been deceived and betrayed by his best friends.

At some point during the party Junge stopped her typing and walked across the corridor to the room where the party was taking place to express her congratulations to the newlyweds and wish them luck. She stayed for less than fifteen minutes and then returned to her typing. During the time she was typing, Hitler left the party and came in three times in order to ask how far she had gotten. According to Junge, Hitler would look in and say “Are you ready?” and she said, “No my Führer, I am not ready yet.” Bormann and Goebbels also kept coming to see if she was finished. Not only did these comings and goings make Junge nervous and delay the process, but being upset about the whole situation, Junge made several typographical errors. Those were only crossed out in ink.

Also complicating the finishing of the typing was that the names of some appointments of the new Doenitz government needed to be added to the political testament. During the course of the wedding party, Hitler discussed and negotiated the matter with Bormann and Goebbels. While she was typing the clean copies of the political testament from her shorthand notes, Goebbels or Bormann came in alternately to give her the names of the ministers of the future government, a process that lasted until she had finished typing the three copies.

Towards 05:00, Junge finished typing the three copies each of the political testament and personal will. They were timed at 04:00 as that was when she had begun her typing of the first copy of the political testament. Just as she finished, Goebbels came to her and wanted the documents, almost tearing the last piece of paper from the typewriter. She gave them to Goebbels without having a chance to review the final product because Goebbels was in such a hurry. She asked Goebbels whether they still wanted her. Goebbels said “no, lie down and have a rest.” Junge went into one of the room where there were sleeping accommodations and lay down. At that point Eva Braun had already retired and the wedding party had ended or just about to end. Goebbels, meanwhile, took the copies of the documents to Hitler.

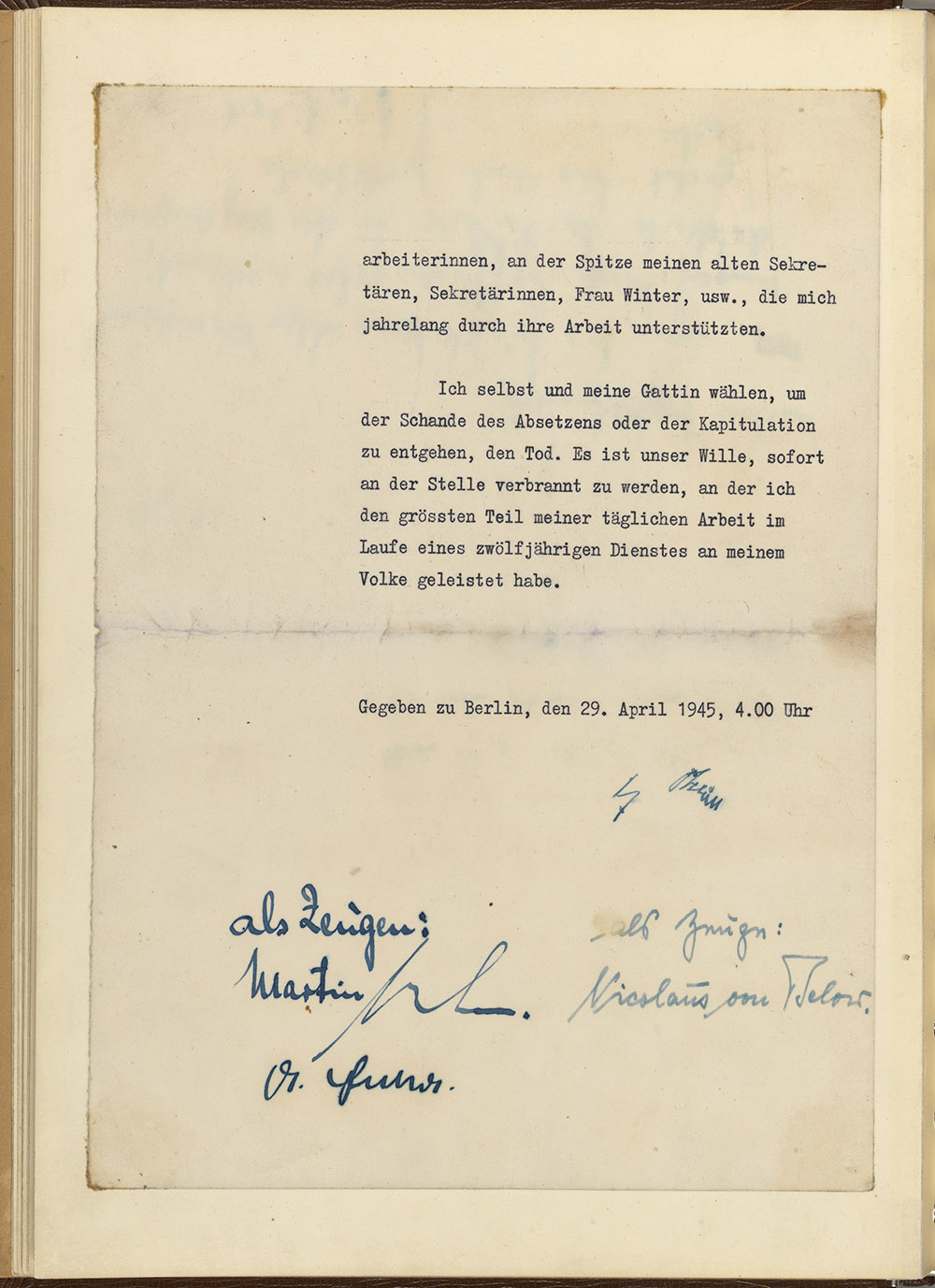

The documents were ready to be signed. First Hitler asked Goebbels and Bormann whether everything was correct. Apparently they answered in the affirmative. The personal will was signed by Hitler and signed by the witnesses: Bormann, Goebbels, and von Below. The political testament was also signed at the same time by Hitler and the witnesses Goebbels, Bormann, Burgdorf, and Krebs. After signing the wills, sometime before 06:00, Hitler retired to rest.

At around 0600 April 29, 1945, the regular intense Russian artillery bombardment began with the whole area around the Reich Chancellery and the government district coming under fire. The Soviets launched their all-out offensive against the center of Berlin — fighting was soon in progress on Kurfuestendamm and on Bismarckstrasse and Kantstrasse. The front line was now only some 450 yards from the Chancellery.

During those same early morning hours, Adolf Hitler planned for the three copies of his personal testament and personal will to be taken out of Berlin and delivered to Grand Admiral Doenitz and Field Marshal Schoerner, commander of Army Group Center in Bohemia (and, by way of Hitler’s political testament, newly appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Army). These were carried by Major Johannmeier (Hitler’s 31 year old adjutant to the Army) SS-Colonel Wilhelm Zander (an aide representing Bormann), and Heinz Lorenz (an official of the Propaganda Ministry representing Goebbels). These two men would receive separate instructions. Johannmeier was charged to escort the party on their journey through enemy lines.

With the will and testament in his possession, Johannmeier went to see Hitler around 09:00. Hitler told him that this testament must be brought out of Berlin at any price, that Schoerner must receive it, and that he believed he would succeed in the task. Johannmeier said they both realized that they would not see each other again and this influenced the tone in which they said goodbye. Hitler spoke very cordially. Hitler shook his hand. Johannmeier realized that Hitler was going to die.

While Johannmeier, Zander, and Lorenz were getting their instructions, the Russian attack drew ever relentlessly near the bunker. At about 09:00, the Russian artillery fire suddenly stopped, and shortly afterwards runners reported to the Bunker that the Russians were advancing with tanks and infantry towards the Wilhelmplatz. It grew quite silent in the bunker and there was great tension among its occupants. Later on that morning Secretary Gertrude Junge went back to Hitler’s bunker to see whether any changes had taken place. She noted that Hitler was uneasy and walked from one room to another. Hitler told her he would wait until the couriers had arrived at their destinations with the testaments and then would commit suicide.

At noon, with the Russians closing in on Hitler’s bunker, Hitler held his situation conference. Joining Hitler were Bormann, Krebs, Burgdorf, Goebbels, and a few others. Also around noon, the couriers (Lorenz in civilian clothes; Zander in his SS uniform; and Johannmeier in a military uniform) joined Corporal Heinz Hummerich (a clerk in the Adjutancy of the Führer Headquarters) left the bunker, and headed west.

During the course of April 29, Hitler learned that his ally, Benito Mussolini, had been executed by Italian partisans. The bodies of Mussolini and his mistress, Clara Petacci, had been strung up by their heels. The corpses were later cut down and thrown into the gutter, where vengeful Italians reviled them. These events probably strengthened Hitler’s resolve not to allow himself or his wife to be made “a spectacle of”, as he had earlier recorded in his Testament. That afternoon, Hitler expressed doubts about the cyanide capsules he had received through Himmler’s SS. To verify the potency of the capsules, Hitler ordered Dr. Werner Haase to test one on his dog Blondi, who died as a result.

Late in the evening of April 29, Krebs contacted Jodl by radio: “Request immediate report. Firstly of the whereabouts of Wenck’s spearheads. Secondly of time intended to attack. Thirdly of the location of the Ninth Army. Fourthly of the precise place in which the Ninth Army will break through. Fifthly of the whereabouts of General Rudolf Holste’s spearhead.” In the early morning of April 30, Jodl replied to Krebs: “Firstly, Wenck’s spearhead bogged down south of Schwielow Lake. Secondly, Twelfth Army therefore unable to continue attack on Berlin. Thirdly, bulk of Ninth Army surrounded. Fourthly, Holste’s Corps on the defensive.” By 01:00, General Wilhelm Keitel had reported that all forces that Hitler had been depending on to rescue Berlin had either been encircled or forced onto the defensive.

SS-Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke, commander of the center government district of Berlin, informed Hitler during the morning of April 30 that he would be able to hold for less than two days. Late that morning, with the Soviets less than 1,600 feet (500 meters) from the bunker, Hitler had a meeting with General Helmuth Weidling, the commander of the Berlin Defense Area. He told Hitler that the garrison would probably run out of ammunition that night and that the fighting in Berlin would inevitably come to an end within the next 24 hours. Weidling asked Hitler for permission for a breakout; this was a request he had unsuccessfully made before. Hitler did not answer, and Weidling went back to his headquarters in the Bendlerblock. At about 13:00 he received Hitler’s permission to try a breakout that night.

Hitler, two secretaries, and his personal cook then had lunch, after which Hitler and Braun said farewell to members of the Führerbunker staff and fellow occupants, including Bormann, Joseph Goebbels and his family, the secretaries, and several military officers. At around 14:30 Adolf and Eva Hitler went into Hitler’s personal study.

Several witnesses later reported that they heard a loud gunshot at approximately 15:30. After waiting a few minutes, Hitler’s valet, Heinz Linge, opened the study door with Bormann at his side. Linge later stated that he immediately noted a scent of burnt almonds, which is a common observation in the presence of prussic acid (the aqueous form of hydrogen cyanide). Hitler’s adjutant, SS-Sturmbannführer Otto Günsche, entered the study and found the two lifeless bodies on the sofa. Eva, with her legs drawn up, was to Hitler’s left and slumped away from him. Günsche stated that Hitler “… sat … sunken over, with blood dripping out of his right temple. He had shot himself with his own pistol, a Walther PPK 7.65”. The gun lay at his feet and according to SS-Oberscharführer Rochus Misch, Hitler’s head was lying on the table in front of him. Blood dripping from Hitler’s right temple and chin had made a large stain on the right arm of the sofa and was pooling on the carpet. According to Linge, Eva’s body had no visible physical wounds, and her face showed how she had died — by cyanide poisoning. She was just 33 years old. Günsche and SS-Brigadeführer Wilhelm Mohnke stated “unequivocally” that all outsiders and those performing duties and work in the bunker “did not have any access” to Hitler’s private living quarters during the time of death (between 15:00 and 16:00).

Günsche left the study and announced that the Führer was dead. In accordance with Hitler’s prior written and verbal instructions, the two bodies were carried up the stairs to ground level and through the bunker’s emergency exit to the garden behind the Reich Chancellery, where they were doused with petrol. Eyewitness Rochus Misch reported someone shouting, “Hurry upstairs, they’re burning the boss!” After the first attempts to ignite the petrol did not work, Linge went back inside the bunker and returned with a thick roll of papers. Bormann lit the papers and threw the torch onto the bodies. As the two corpses caught fire, a small group, including Bormann, Günsche, Linge, Goebbels, Erich Kempka, Peter Högl, Ewald Lindloff, and Hans Reisser, raised their arms in salute as they stood just inside the bunker doorway.

At around 16:15, Linge ordered SS-Untersturmführer Heinz Krüger and SS-Oberscharführer Werner Schwiedel to roll up the rug in Hitler’s study to burn it. Schwiedel later stated that upon entering the study, he saw a pool of blood the size of a “large dinner plate” by the arm-rest of the sofa. Noticing a spent cartridge case, he bent down and picked it up from where it lay on the rug about 1 mm from a 7.65 pistol. The two men removed the blood-stained rug, carried it up the stairs and outside to the Chancellery garden. There the rug was placed on the ground and burned.

The Soviets shelled the area in and around the Reich Chancellery on and off during the afternoon. SS guards brought over additional cans of petrol to further burn the corpses. Linge later noted the fire did not completely destroy the remains, as the corpses were being burned in the open, where the distribution of heat varies. The corpses burned from 16:00 to 18:30. At approximately 18:30, Lindloff and Reisser covered up the remains in a shallow bomb crater.

At 14:46 on May 1, Goebbels — about six hours before committing suicide, sent Doenitz a message (received at 15:18) that Hitler had died at 15:30 on April 30, and that his Testament of April 29:

“appoints you as Reich President, Reich Minister Dr. Goebbels as Reich Chancellor, Reichsleiter Bormann as Party Minister, Reich Minister Seyss-Inquart as Foreign Minister. By order of the Führer, the Testament has been sent out of Berlin to you, to Field-Marshal Schoerner, and for preservation and publication. Reichsleiter Bormann intends to go to you today and to inform you of the situation. Time and form of announcement to the Press and to the troops is left to you. Confirm receipt.-Goebbels.”

On the morning of May 1 (thirteen hours after the event), Stalin was informed of Hitler’s suicide. General Hans Krebs had given this information to Soviet General Vasily Chuikov when they met at 04:00 that morning, when the Germans attempted to negotiate acceptable surrender terms. Stalin demanded unconditional surrender and asked for confirmation that Hitler was dead. He wanted Hitler’s corpse found.

In the late afternoon of May 1, Goebbels had his children poisoned, and he and his wife left the bunker at around 20:30. There are several different accounts on what followed. According to one account, Goebbels shot his wife and then himself. Another account was that they each bit on a cyanide ampule and were given a coup de grâce immediately afterwards. Goebbels’ SS adjutant Günther Schwägermann testified in 1948 that the couple walked ahead of him up the stairs and out to the Chancellery garden. He waited in the stairwell and heard the shots, then walked up the remaining stairs and saw the lifeless bodies of the couple outside. He then followed Joseph Goebbels’ order and had an SS soldier fire several shots into Goebbels’ body, which did not move. The bodies were then doused with petrol and set alight, but the remains were only partially burned and not buried.

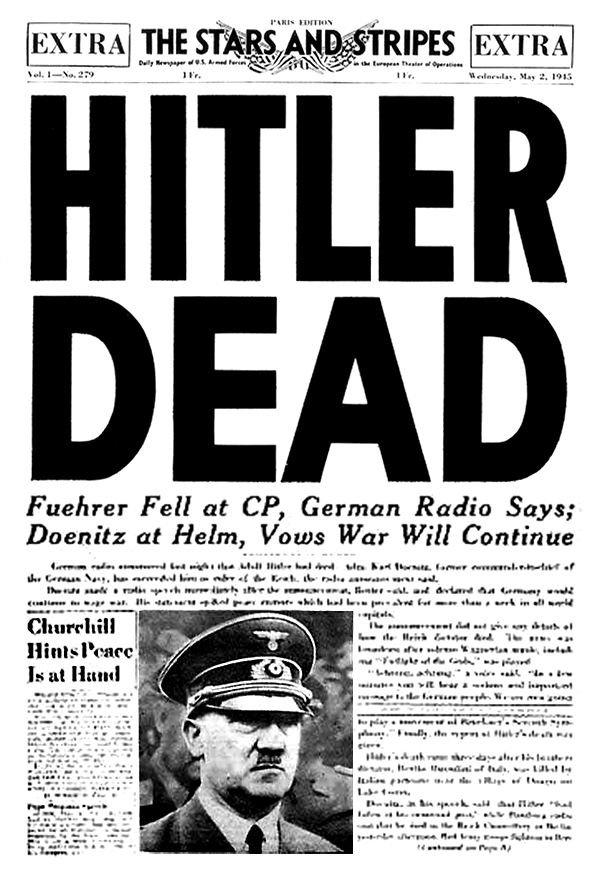

The first inkling to the outside world that Hitler was dead came from the Germans themselves. At 22:26 on the night of May 1, the radio station Reichssender Hamburg interrupted their normal program to announce that an important broadcast would soon be made. After dramatic funeral music by Wagner and Bruckner, Grand Admiral Karl Donitz announced that Hitler was dead. Dönitz called upon the German people to mourn their Führer, who died a hero defending the capital of the Reich. He also announced his own succession.

Weidling had given the order for the survivors at the Reich Chancellery to break out to the northwest, and the plan got underway at around 23:00. The first group was led by Mohnke; they tried unsuccessfully to break through the Soviet rings and were captured the next day. Mohnke was interrogated by SMERSH, like others who were captured from the Führerbunker. The third breakout attempt from the Reich Chancellery was made around 01:00 on May 2, and Bormann managed to cross the Spree. Arthur Axmann followed the same route and reported seeing Bormann’s body a short distance from the Weidendammer bridge. At 01:00, the Soviet forces picked up a radio message from the LVI Panzer Corps requesting a cease-fire. Down in the Führerbunker, General Krebs and General Wilhelm Burgdorf committed suicide by gunshot to the head.

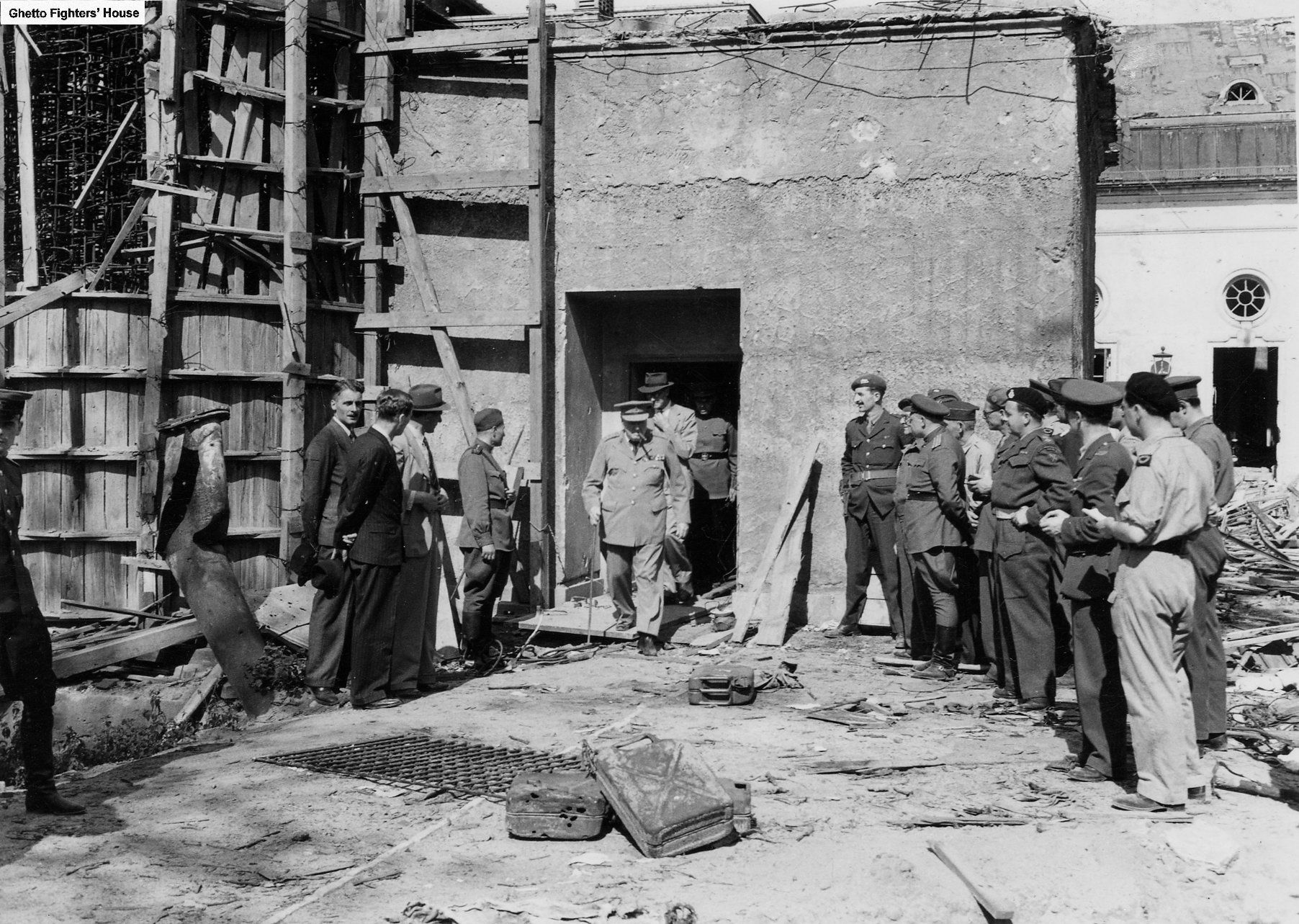

The last defenders in the area of the bunker complex were French SS volunteers of the 33rd Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Charlemagne (1st French), and they remained until the early morning. The Soviet forces then captured the Reich Chancellery. General Weidling surrendered with his staff at 06:00, and his meeting with Chuikov ended at 08:23. Johannes Hentschel, the master electro-mechanic for the bunker complex, stayed after everyone else had either left or committed suicide, as the field hospital in the Reich Chancellery above needed power and water. He surrendered to the Red Army as they entered the bunker complex at 09:00 on May 2.

Later on May 2, the remains of Hitler, Braun, and two dogs (thought to be Blondi and her offspring, Wulf) were discovered in a shell crater by a unit of the Red Army intelligence agency SMERSH tasked with finding Hitler’s body. Stalin was wary of believing Hitler was dead, and restricted the release of information to the public. By May 11, Hitler’s dentist, Hugo Blaschke, dental assistant Käthe Heusermann and dental technician Fritz Echtmann confirmed that the dental remains belonged to Hitler and Braun. The remains of Hitler and Braun were repeatedly buried and exhumed by SMERSH during the unit’s relocation from Berlin to a new facility in Magdeburg, East Germany. The bodies, along with the charred remains of propaganda minister Goebbels, his wife Magda, and their six children, were buried in an unmarked grave beneath a paved section of the front courtyard. The location was kept secret.

Hoping to save the army and the nation by negotiating a partial surrender to the British and Americans, Dönitz authorized a fighting withdrawal to the west. His tactic was somewhat successful: it enabled about 1.8 million German soldiers to avoid capture by the Soviets, but it came at a high cost in bloodshed, as troops continued to fight until May 8.

As Berlin surrendered, Lorenz, Zander, Johannmeier, and Hummerich were on the Havel River on May 2. Before dawn on May 3, they made their way to Potsdam and Brandenburg, and on May 11 crossed the Elbe at Parey, between Magdeburg and Genthin, and ultimately, as foreign workers, passed into the area of the Western Allies, transported by American trucks. By this time the war was over, and Zander and Lorenz lost heart and easily convinced themselves that their mission now had no purpose or possibility of fulfillment. Johannmeier allowed himself to be influenced by them, although he still believed he would have been able to complete his mission.

After abandoning their mission, the four men split up. Zander and Lorenz went to the house of Zander’s relatives in Hannover. From there, Zander proceeded south until he reached Munich where he stayed with his wife, and then continued to Tegernsee. At Tegernsee, Zander hid his documents in a trunk. He changed his name, identity, status, and began a new life under the name of Friedrich Wilhelm Paustin. Johannmeier meanwhile went to his family’s home in Iserlohn in Westphalia, and buried his documents in a bottle in the back garden. Lorenz ended up in Luxembourg and found work as a journalist under an assumed name.

Lorenz and the documents he was carrying were seized by the British Army, in the British Zone of Occupation of Germany, in November 1945. The Americans captured Zander and the documents he was carrying (including the original marriage license of Hitler and Braun, and the hand-written letter of transmittal for the documents from Bormann to Doenitz) with the assistance of British intelligence officer Major H. Trevor-Roper, in Bavaria on December 28.

After Zander’s arrest, interest switched to Johannmeier, who had been living quietly with his parents in Iserlohn, in the British Zone of Occupation. Trevor-Roper had him detained and interrogated on December 20. Johannmeier maintained that he had no documents, but had just escorted Zander and Lorenz out of Berlin. Trevor-Roper met with Major Johannmeier on January 1, 1946, and explained to him that Zander and Lorenz were both in Allied hands (he had already read in the newspapers about Zander’s arrest), and that in view of their independent but unanimous testimony, it was impossible to accept his statement that he had been merely an escort, and had not himself carried any documents. He nevertheless maintained his story. He agreed that the evidence was against him, but insisted that his story was true. Shortly after the New Year holiday, while alone with Trevor-Roper, Johannmeier admitted, “I have the papers.” He stated that he had buried them in a garden of his home in Iserlohn, in a glass jar; and he agreed to lead Trevor-Roper to the spot.

On the long drive back to Iserlohn, Johannmeier spoke freely on various topics which were discussed. When they stopped for a meal, Trevor-Roper asked him why he had decided to reveal the truth. Johannmeier said he had reflected that if Zander and Lorenz had so easily consented to betray the trust reposed in them, it would be quixotic for him, who was not a member of the Party or connected with politics, but who was merely carrying the documents in obedience to a military order, to endure further hardship to no practical purpose. In Iserlohn they left the car some distance away at Johannmeier’s request — he did not want the neighbors to see a British staff car outside of his parents’ home. The two men walked together through the cold to the house. It was now night-time and the ground had frozen hard. Johannmeier found an axe and together they walked out into the back corner of his garden. Johannmeier found the place, broke frozen surface of the ground with the axe, and dug up the glass bottle. Then he smashed the bottle with the head of the axe and drew out the documents which he handed over to Trevor-Roper. They were the third copy of Hitler’s private will and personal testament plus a covering letter from Burgdorf to Schoerner. The Allies now had the three sets of documents that had been carried out of the bunker on April 29, 1945.

On February 28, 1946, Colonel Richard L. Hopkins, Deputy Chief, Military Intelligence Service (MIS) sent Lt. Gen. Hoyt S. Vandenberg, the new Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, the originals of Hitler’s certificate of marriage, will and testament, together with Bormann’s letter of transmittal to Doenitz. Hopkins informed Vandenberg that the documents had been appropriately mounted in a protective binder together with translations of the documents. He suggested that the significance of the papers was such that they be presented to the President with the suggestion that the documents be forwarded to the Library of Congress or other appropriate agency for preservation and suitable public display. He attached a draft letter to the President and requested Vandenberg to approve his recommendation. Later that day, according to a pencil notation on the retained copy, the documents were hand carried to the Office of the Chief of Staff.

Action was not taken immediately. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Army Chief of Staff, decided that before sending the Hitler documents to the President, they should be authenticated by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Colonel Hopkins thus got in touch with the FBI. On March 6, E. G. Fitch of the FBI sent a memorandum to FBI Assistant Director D. M. Ladd along with the documents and various other papers bearing Adolf Hitler’s signature. At the bottom of the memorandum was J. Edgar Hoover’s blue-inked “OK. H.”

The FBI lab completed its work on March 13 and Joseph A. Sizoo, the Chief of the Document Section of the lab transmitted its report on the document analysis to the Bureau hierarchy. Sizoo reported that the papers were, when received, mounted on cardboard pages of a leather binder, each being covering with cellulose sheets fastened with scotch tape for protection. To conduct the necessary examination, in accordance with express statements of MIS, he reported that several pages were removed from the covers. Since this endangered the specimens and additional preparations will be needed for permanent maintenance, this removal was confined to the minimum “‘random tests.’” Pages 1 and 2 of the marriage certificate (the most questionable), the last (signature) pages of the private will and the political testament were the only sheets completely removed. One or two of the covers of other pages were lifted to gain access to the paper, but otherwise the mounts were not disturbed. Sizoo reported that it had been found that rubber cement was used at the top and corners to fasten the original papers to the cardboard. In replacing those removed, no additional adhesive was added and at no time was anything placed on the papers. Sizoo also provided alternatives for permanent retention and display, citing methods used by the National Archives and Library of Congress and indicated that the Bureau might want to suggest those methods to the MIS. He concluded by indicating that the present mountings were restored in the leather binder and specimens were transmitted with his memorandum for personal delivery to MIS with the report if desired. He also noted that photographic copies had been prepared for the records of the Laboratory. Hoover wrote in blue ink “Yes. H.” and also in blue ink that Hopkins was advised as above.

On March 19, Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson wrote the President Harry S. Truman:

Our Military Intelligence personnel, through information furnished by the British Intelligence Service, recovered Adolf Hitler’s personal and political wills, his marriage certificate, and a letter transmitting these documents to Admiral Doenitz, signed Martin Bormann. The unique character of these papers and their historic significance prompt me to forward them to you as a matter of personal interest. A laboratory test by the Federal Bureau of Investigation indicates that these documents are authentic.

Hitler’s final anti-Semitic tirate (sic), his frantic attempt to maintain a semblance of German government, and what amounts to a suicide pact between himself and Eva Braun vividly illustrates the closing hours of the Nazi regime. These are matters of great public interest. Might I suggest that these documents be placed on display in the Library of Congress or other suitable establishment.

President Truman on March 22 wrote Patterson thanking him for the Hitler material. He indicated that he was pleased to have looked at them before they went to the National Archives, where the other war documents were held. The Hitler documents went on exhibit at the National Archives on April 26, 1946, less than a year after the documents had been created in the Führerbunker in Berlin.

For politically motivated reasons, the Soviet Union presented various versions of Hitler’s fate. In the years immediately following 1945, the Soviets maintained Hitler was not dead, but had fled and was being shielded by the former western allies, despite having identified his and Braun’s remains in May 1945. This worked for a time to create doubt among western authorities. The chief of the U.S. trial counsel at Nuremberg, Thomas J. Dodd, said: “No one can say he is dead.” When President Harry S. Truman asked Stalin at the Potsdam Conference in August 1945 whether or not Hitler was dead, Stalin replied bluntly, “No”. In November 1945, Dick White, then head of counter-intelligence in the British sector of Berlin (and later head of MI5 and MI6 in succession), had their agent Hugh Trevor-Roper investigate the matter to counter the Soviet claims. His findings were written in a report and published in book form in 1947.

In May 1946, SMERSH agents recovered from the crater where Hitler was buried two burned skull fragments with gunshot damage. These remains were apparently forgotten in the Russian State Archives until 1993, when they were re-found. In 2009, DNA and forensic tests were performed on the skull fragment, which Soviet officials had long believed to be Hitler’s. According to the American researchers, the tests revealed that the skull was actually that of a woman and the examination of the sutures where the skull plates come together placed her age at less than 40 years old. The jaw fragments which had been recovered in May 1945 were not tested.

In 1969, Soviet journalist Lev Bezymensky’s book on the death of Hitler was published in the West. It included the SMERSH autopsy report, but because of the earlier disinformation attempts, western historians thought it untrustworthy.

In 1970, the SMERSH facility, by then controlled by the KGB, was scheduled to be handed over to the East German government. Concerned that a known Hitler burial site might become a Neo-Nazi shrine, KGB director Yuri Andropov authorized an operation to destroy the remains that had been buried in Magdeburg on February 21, 1946. A Soviet KGB team was given detailed burial charts. On April 4, 1970, they secretly exhumed five wooden boxes containing the remains of “10 or 11 bodies … in an advanced state of decay”. The remains were thoroughly burned and crushed, after which the ashes were thrown into the Biederitz river, a tributary of the nearby Elbe.

According to Ian Kershaw, the corpses of Braun and Hitler were already thoroughly burned when the Red Army found them, and only a lower jaw with dental work could be identified as Hitler’s remains.

The ruins of both Chancellery buildings were levelled by the Soviets between 1945 and 1949 as part of an effort to destroy the landmarks of Nazi Germany. The bunker largely survived, although some areas were partially flooded. In December 1947, the Soviets tried to blow up the bunker, but only the separation walls were damaged. In 1959, the East German government began a series of demolitions of the Chancellery, including the bunker. Because it was near the Berlin Wall, the site was undeveloped and neglected until 1988–1989. During extensive construction of residential housing and other buildings on the site, work crews uncovered several underground sections of the old bunker complex; for the most part these were destroyed. Other parts of the Chancellery underground complex were uncovered, but these were ignored, filled in, or resealed.

Government authorities wanted to destroy the last vestiges of these Nazi landmarks. The construction of the buildings in the area around the Führerbunker was a strategy for ensuring the surroundings remained anonymous and unremarkable. The emergency exit point for the Führerbunker (which had been in the Chancellery gardens) was occupied by a car park.

On June 8, 2006, during the lead-up to the 2006 FIFA World Cup, an information board was installed to mark the location of the Führerbunker. The board, including a schematic diagram of the bunker, can be found at the corner of In den Ministergärten and Gertrud-Kolmar-Straße, two small streets about three minutes’ walk from Potsdamer Platz. Hitler’s bodyguard, Rochus Misch, one of the last people living who was in the bunker at the time of Hitler’s suicide, was on hand for the ceremony.

The rest of Braun’s family survived the war. Her mother, Franziska, died at age 96 in January 1976, having lived out her days in an old farmhouse in Ruhpolding, Bavaria. Her father, Fritz, died in 1964. Gretl gave birth to a daughter — whom she named Eva — on May 5, 1945. She later married Kurt Beringhoff, a businessman. She died in 1987. Braun’s elder sister, Ilse, was not part of Hitler’s inner circle. She married twice and died in 1979.

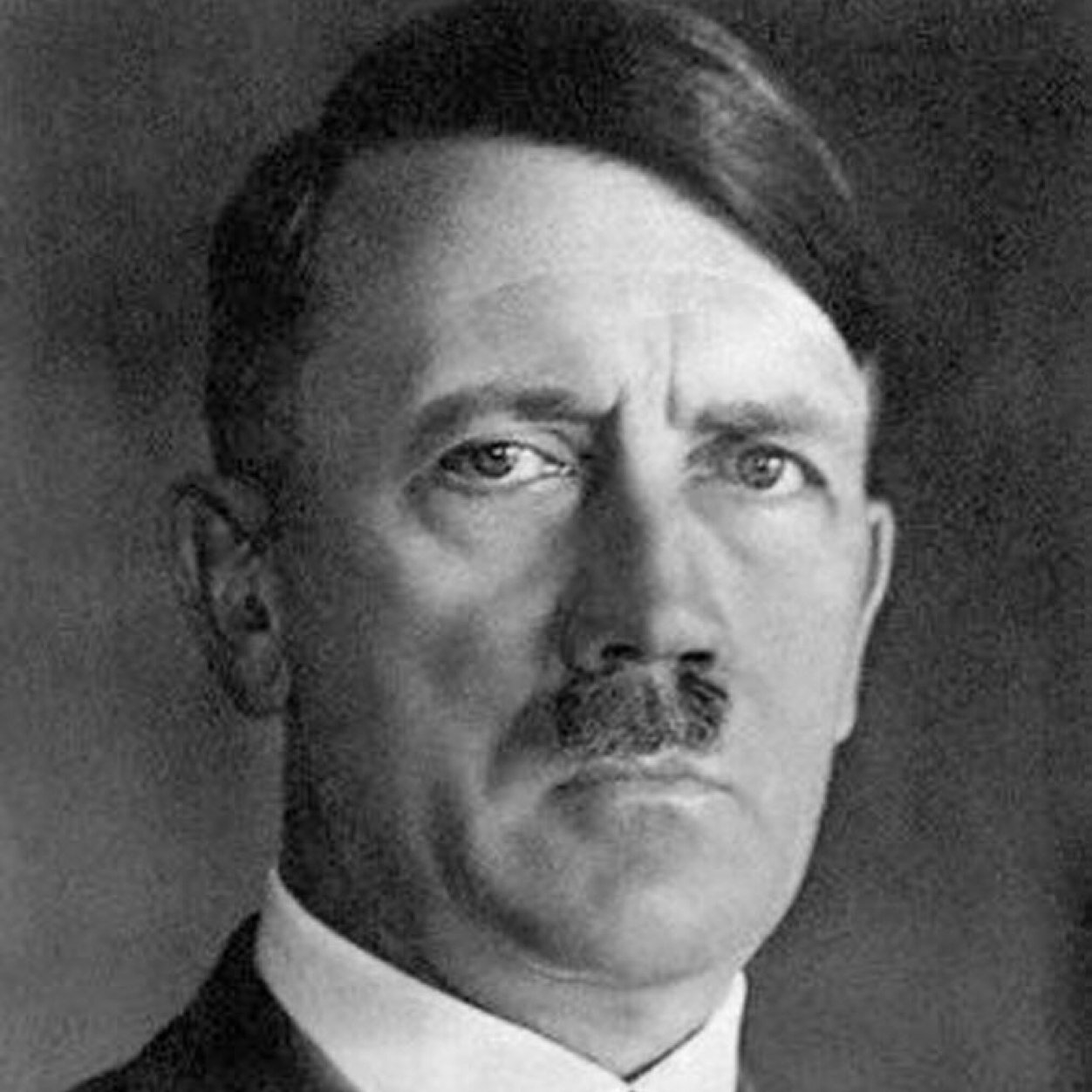

When my friends and co-workers discover that I collect stamps, the first question asked by non-Asians is almost invariably, “Do you have any Hitler stamps?” I always find this to be an odd question but most of the Westerners who ask it are people my age or older. When I was a kid growing up in the United States during the early 1970s, it was quite common to find packets of stamps in the local department stores and these often had plenty of the 1941-1944 definitives bearing the right-facing portrait of Adolf Hitler (Scott #506-527 and #529). Perhaps it now the most remembered stamp design by non-collectors of my generation (with the possible exception of the Penny Black). They are sometimes referred to as “Hitler Heads.”

During the “Third Reich” the Reichspost continued to function as a monopoly of the government under the auspices of the Reichspostministerium, and Nazi propaganda took hold and influenced stamp design and policy. As leader of Germany and the Nazi party, Adolf Hitler demanded that his image be placed on postage stamps. By printing these stamps and thus forcing German people to use them in their everyday lives, Hitler successfully promoted himself, the war, and the Nazi party during the hardships of World War II. His image on the stamps actually generated a commission for each stamp that was sold, not unlike today’s licensing agreements of famous figures.

Propaganda efforts, inflation, and perhaps Hitler’s pride spurred the printing of these stamps in increasing quantities as the war became more desperate for Germany. Finally, literally millions of these stamps were “liberated” from Germany by Allied soldiers as they overran towns, banks, and post offices. Many families, even today, have some or all of these stamps tucked away in a truck and wrapped in stories of a relative who served in the Second World War and returned home with the stamps as souvenirs of their pains and final victory.

There were eight small-format (measuring 18½mm x 22½mm) stamps printed by typography on laid paper (auf gestrichenem Papier), perforated 14, which were released beginning on August 1, 1941:

- Scott #506: 1 pfennig – gray black; also issued in booklet panes (December 1941)

- Scott #507: 3 pfennig – light brown; issued in booklet panes (December 1941); also exists imperforate

- Scott #508: 4 pfennig – slate; issued in booklet panes (December 1941)

- Scott #509: 5 pfennig – deep yellow green

- Scott #510: 6 pfennig – purple; issued in booklet panes (December 1941); also exists imperforate

- Scott #511: 8 pfennig – red; also exists imperforate

- Scott #511A: 10 pfennig – dark brown (released in December 1942); also exists imperforate

- Scott #511B: 12 pfennig – carmine (released in December 1942)

Six of the small-format stamps were engraved on normal paper, perforated 14, and released on August 1, 1941:

- Scott #512: 10 pfennig – dark brown

- Scott #513: 12 pfennig – bright carmine; issued in booklet panes

- Scott #514: 15 pfennig – brown lake

- Scott #515: 16 pfennig – peacock green

- Scott #516: 20 pfennig – blue

- Scott #517: 24 pfennig – orange brown

There were eleven denominations printed by engraving on normal paper which were in a larger-sized format (measuring 21½ x 26mm). The high pfennig denominations were released on August 1, 1941; four mark values were released on March 20, 1942, perforated 12½ and reissued perforated 14 in 1944, with one additional denomination added to the last batch:

- Scott #518: 25 pfennig – bright ultramarine

- Scott #519: 30 pfennig – olive green

- Scott #520: 40 pfennig – bright red violet; also exists imperforate

- Scott #521: 50 pfennig – myrtle green

- Scott #522: 60 pfennig – dark red brown

- Scott #523: 80 pfennig – indigo

- Scott #524: 1 mark – dark slate green; released in 1944; also exists imperforate

- Scott #524a: 1 mark – dark slate green; perforated 12½; released in 1942

- Scott #525: 2 marks – violet; released in 1944; also exists imperforate

- Scott #525a: 2 marks – violet; perforated 12½; released in 1942

- Scott #526: 3 marks – copper red; perforated 12½; released in 1942

- Scott #526a: 3 marks – copper red; released in 1944; also exists imperforate

- Scott #527: 5 marks – dark blue; perforated 12½; released in 1942

- Scott #527a: 5 marks – dark blue; released in 1944

- Scott #529: 42 pfennig – bright green; released in 1944; also exists imperforate

From 1941-1943, all 20 of the pfennig denominations (excepting Scott #529, the 42-pfennig released in 1944) were overprinted OSTLAND (for “Eastern Front”) for use during the German invasion of the Baltic States Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania (Russia Scott #N9-N28). They were also overprinted UKRAINE (Russia Scott #N29-N48).

Scott #513 was released on August 1, 1941, in sheet form and then in December of the same year in booklets. The booklets contained five panes, each with different denominations of stamps with the fifth pane containing six copies of the 12-pfennig bright carmine engraved stamp, perforated 14, plus two labels. The labels as illustrated here read:

“Unterstützt das Deutsche Rote Kreuz! Tretet in die NSV ein!”

This translates to “Support the German Red Cross! Join the NSV!”

The NSV was the Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt, meaning National Socialist People’s Welfare, a social welfare organization during the Third Reich established in 1933 shortly after the NSDAP took power in Germany. Its seat was in Berlin.

Erich Hilgenfeldt, who worked as office head at the NSV, had organized a charity drive to celebrate Hitler’s Birthday on April 20, 1931. Following this, Joseph Goebbels named him the leader of the NSV. The NSV became established as the single Nazi Party welfare organ in May 1933. On September 21, in the same year Hilgenfeldt was appointed as Reich Commissioner for the Winterhilfswerk (Winter Support Program). Under Hilgenfeldt, the program was massively expanded, so that the régime deemed it worthy to be called the “greatest social institution in the world.”

One method of expansion was to absorb, or in NSDAP parlance “coordinate”, already existing but non-Nazi charity organizations. In 1933, Hitler decreed the banning of all private charity organizations in Germany, ordering NSV chairman Erich Hilgenfeldt to “see to the disbanding of all private welfare institutions,” which provided the National Socialists the means to engage in the social engineering of society through the selection of who could receive government benefits. Hitler had essentially nationalized local municipalities, German federal states and private delivery structures that had provided welfare services to the public. NSV was the second largest Nazi group organization by 1939, second only to the German Labor Front.

With 17 million Germans receiving assistance under the auspices of National Socialist People’s Welfare (NSV) by 1939, the agency “projected a powerful image of caring and support.” The National Socialists provided a plethora of social welfare programs under the Nazi concept of Volksgemeinschaft which promoted the collectivity of a “people’s community” where citizens would sacrifice themselves for the greater good. The NSV operated “8,000 day-nurseries” by 1939, and funded holiday homes for mothers, distributed additional food for large families, and was involved with a “wide variety of other facilities.”

The Nazi social welfare provisions included old age insurance, rent supplements, unemployment and disability benefits, old-age homes, interest-free loans for married couples, along with healthcare insurance, which was not decreed mandatory until 1941. One of the NSV branches, the Office of Institutional and Special Welfare, was responsible “for travelers’ aid at railway stations; relief for ex-convicts; support for re-migrants from abroad; assistance for the physically disabled, hard-of-hearing, deaf, mute, and blind; relief for the elderly, homeless and alcoholics; and the fight against illicit drugs and epidemics.”

The Office of Youth Relief, which had 30,000 branch offices by 1941, took the job of supervising “social workers, corrective training, mediation assistance,” and dealing with judicial authorities to prevent juvenile delinquency.

One of the NSV’s premier activities was Winter Relief of the German People, which coordinated an annual drive to collect charity for the poor under the slogan: “None shall starve or freeze.” These social welfare programs represented a Hitlerian endeavor to lift the community above the individual while promoting the wellbeing of all bona fide citizens. As Hitler told a reporter in 1934, he was determined to give Germans “the highest possible standard of living.”

During World War II, the NSV took over more and more governmental responsibilities, especially in the fields of child and youth labor. The expenses for the Nazi’s welfare state continued to mount, increasing significantly just before and after the beginning of World War II. In three budgetary years, the funds required by Germany’s social welfare programs had “more than doubled” from 640.4 million Reichmarks in 1938 to 1,395.3 Reichmarks by 1941.

In a social engineering effort, the NSV often refused to provide aid to Jews since they didn’t belong to the German ‘People’s community.’

After Nazi Germany’s defeat in World War II, the American Military Government issued a special law outlawing the Nazi party and all of its branches. Known as “Law number five”, this Denazification decree disbanded the NSV, like all organizations linked to the Nazi Party. The social welfare organizations had to be established anew during the postwar reconstruction of both West and East Germany.

The copy of Scott #513 appearing at the top of this article is digitally cropped from a cover bearing a commemorative postmark sent from my “adopted” spiritual home of Joachimsthal which is currently the Czech Republic town of Jáchymov. Known by its German name of Sankt Joachimsthal (meaning “Saint Joachim’s Valley”) until 1945, it is a spa town in the Karlovy Vary Region of Bohemia at an altitude of 2,405 feet (733 meters) above sea level in the eponymous St. Joachim’s valley in the Ore Mountains, close to the Czech border with Germany.

The town was mostly German-speaking until the end of the Second World War. The silver Joachimsthaler coins minted there since the 16th century became known in German as Thaler for short, which via the Dutch daalder or daler is the origin of the English word “dollar”. In 1938, it was annexed by Germany as part of the Sudetenland. The German-speaking population was expelled in 1945 and replaced by Czech-speaking settlers.

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (Protektorat Böhmen und Mähren in German or Protektorát Čechy a Morava in Czech) began to issue postage stamps in 1939, at the beginning of the German occupation. Due to the very sudden German occupation, the quick establishment of the Protectorate, and the establishment of the puppet Czech government in the Protectorate, there was no time to design and print a new series of postage stamps. As a result, beginning in July 1939, the contemporary stamps of the former nation of Czechoslovakia were overprinted for use in the new Protectorate of Bohemia & Moravia.

At the end of July 1939, the Bohemia and Moravia began issuing their own postage stamp designs and continued to do so until 1945, including a series of definitives portraying a left-facing portrait of Adolf Hitler. I’m not sure why this particular cover is franked with a German stamp rather than one from the Protectorate. The date is unreadable but the cancellation is promoting the use of the hot springs in the town.

For ore about the history of Joachimsthal, please see my previous ASAD article. I also put together an extensive general and postal history of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia as well as an account of the 1329 siege of Medvėgalis by King John of Bohemia. Also, if you are interested, take a look at my account of the World War II exploits of semi-local hero Otakar Jaroš, the first member of a foreign army decorated with the highest Soviet decoration, Hero of the Soviet Union.

One thought on “Eva Braun, the Führerbunker & Hitler’s Marriage”