Henri Membertou was the sakmow (Grand Chief) of the Mi’kmaq First Nations tribe situated near Port Royal, site of the first French settlement in Acadia, present-day Nova Scotia, Canada. Originally sakmow of the Kespukwitk district, he was appointed as Grand Chief by the sakmowk of the other six districts. He was born in 1507 in the Mi ‘Kmaq Nation of Acadia. However, Membertou claimed to be a grown man when he first met Jacques Cartier, which would mean that he was probably born in the early years of the sixteenth century. Membertou and his followers established a mutually beneficial relationship between France and the Mi’kmaq that would remain unbroken until the end of the French rule in Acadia in 1793. Since his death on September 18, 1611, Membertou’s place in the memory of the descendants of the French settlers has reached mythical proportions. Many believe that Membertou was in part responsible for the survival of the permanent settlement of the French in what is now known as Eastern Canada.

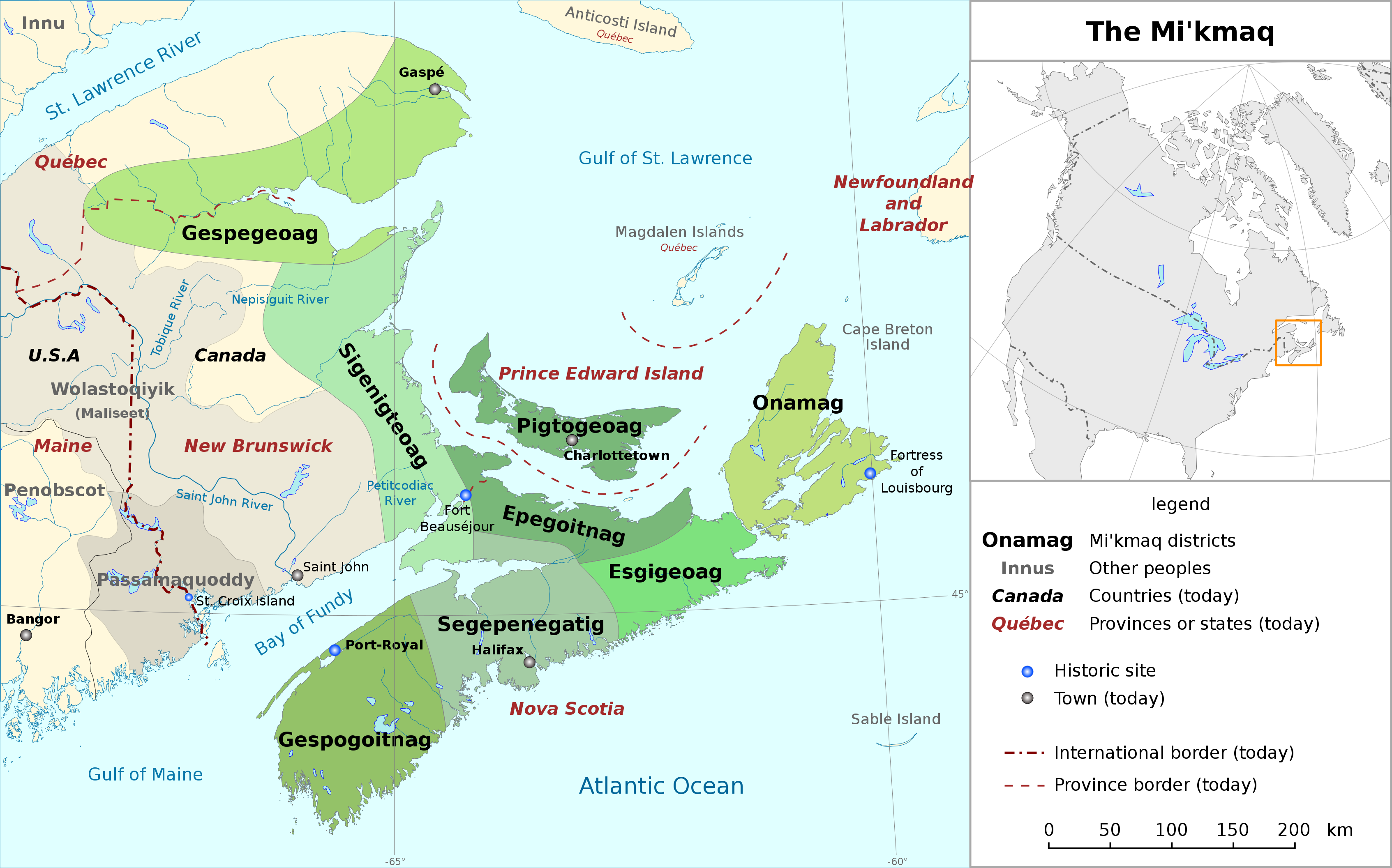

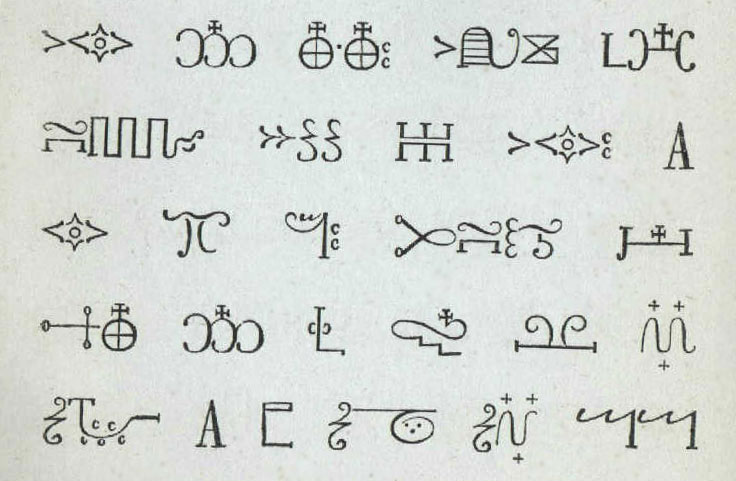

The Mi’kmaq or Mi’gmaq (also Micmac, L’nu, Mi’kmaw or Mi’gmaw) are a First Nations people indigenous to Canada’s Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as the northeastern region of Maine. They call their national territory Mi’kma’ki (or Mi’gma’gi). Today, the nation has a population of about 170,000 (including 18,044 members in the recently formed Qalipu First Nation in Newfoundland), of whom nearly 11,000 speak Mi’kmaq, an Eastern Algonquian language. Once written in Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic writing, it is now written using most letters of the Latin alphabet.

The Santé Mawiómi, or Grand Council, was the traditional senior level of government for the Mi’kmaq people until Canada passed the Indian Act (1876) to require First Nations to establish representative elected governments. After implementation of the Indian Act, the Grand Council took on a more spiritual function. The Grand Council was made up of chiefs of the seven district councils of Mi’kma’ki.

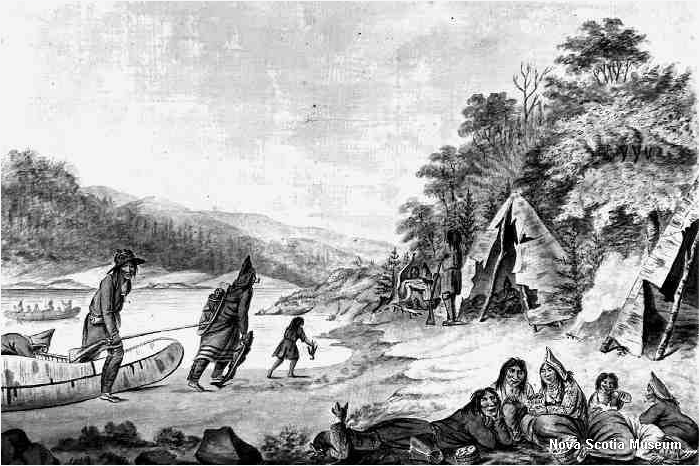

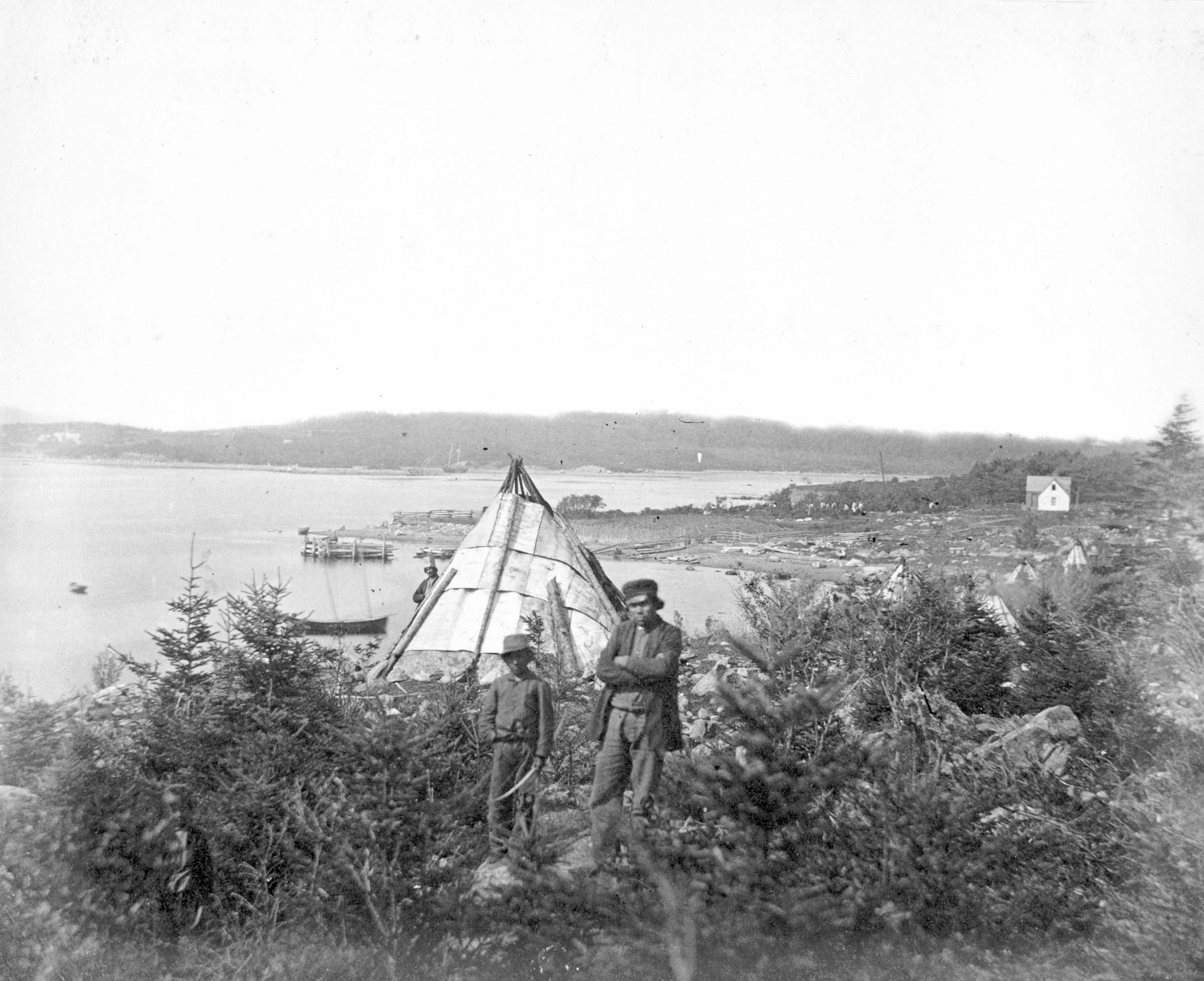

The Mi’kmaq lived in an annual cycle of seasonal movement between living in dispersed interior winter camps and larger coastal communities during the summer. The spawning runs of March began their movement to converge on smelt spawning streams. They next harvested spawning herring, gathered waterfowl eggs, and hunted geese. By May, the seashore offered abundant cod and shellfish, and coastal breezes brought relief from the biting black flies, stouts, midges and mosquitoes of the interior. Autumn frost killed the biting insects during the September harvest of spawning American eels. Smaller groups would disperse into the interior where they hunted moose and caribou. The most important animal hunted by the Mi’kmaq was the moose, which was used in every part: for example, the meat was processed for food, the skin for clothing, tendons and sinew for cordage, and bones for carving and tools. Other animals hunted/trapped included deer, caribou, bear, rabbit, beaver, porcupine and small animals.

Bear teeth and claws were used as decoration in regalia. The women also used porcupine quills to create decorative beadwork on clothing, moccasins, and accessories. The weapon used most for hunting was the bow and arrow. The Mi’kmaq made their bows from maple. They would store lobsters in the ground for later consumption. They ate fish of all kinds, such as salmon, sturgeon, lobster, squid, shellfish, and eels, as well as seabirds and their eggs. They hunted marine mammals: porpoises, whales, walrus, and seals.

Throughout the Maritimes, moose was the most important animal to the Mi’kmaq. It was their second main source of meat, clothing and cordage, which were all crucial commodities. They usually hunted moose in groups of 3 to 5 men. Before the moose hunt, they would starve their dogs for two days to make them fierce in helping to finish off the moose. To kill the moose, they would injure it first, by using a bow and arrow or other weapons. After it was down, they would move in to finish it off with spears and their dogs. The guts would be fed to the dogs. During this whole process, the men would try to direct the moose in the direction of the camp, so that the women would not have to go as far to drag the moose back. A boy became a man in the eyes of the community after he had killed his first moose. It marked the passage after which he earned the right to marry. Once moose were introduced to the island of Newfoundland, the practice of hunting moose with dogs was used in the Bay of Islands region of the province.

The Mi’kmaq territory was the first portion of North America that Europeans exploited at length for resource extraction. Reports by John Cabot, Jacques Cartier, and Portuguese explorers about conditions there encouraged visits by Portuguese, Spanish, Basque, French, and English fishermen and whalers, beginning in the early years of the 16th century. Early European fishermen salted their catch at sea and sailed directly home with it. But they set up camps ashore as early as 1520 for dry-curing cod. During the second half of the century, dry curing became the preferred preservation method.

These European fishing camps traded with Mi’kmaq fishermen; and trading rapidly expanded to include furs. By 1578 some 350 European ships were operating around the Saint Lawrence estuary. Most were independent fishermen, but increasing numbers were exploring the fur trade.

Trading furs for European trade goods changed Mi’kmaq social perspectives. Desire for trade goods encouraged the men devoting a larger portion of the year away from the coast trapping in the interior. Trapping non-migratory animals, such as beaver, increased awareness of territoriality. Trader preferences for good harbors resulted in greater numbers of Mi’kmaq gathering in fewer summer rendezvous locations. This in turn encouraged their establishing larger bands, led by the ablest trade negotiators.

The Mi’kmaq territory was divided into seven traditional districts. Each district had its own independent government and boundaries. The independent governments had a district chief and a council. The council members were band chiefs, elders, and other worthy community leaders. The district council was charged with performing all the duties of any independent and free government by enacting laws, justice, apportioning fishing and hunting grounds, making war and suing for peace.

In addition to the district councils, the M’ikmaq had a Grand Council or Santé Mawiómi. The Grand Council was composed of Keptinaq (captains in English), who were the district chiefs. There were also Elders, the Putús (Wampum belt readers and historians, who also dealt with the treaties with the non-natives and other Native tribes), the women’s council, and the Grand Chief. The Grand Chief was a title given to one of the district chiefs, who was usually from the Mi’kmaq district of Unamáki or Cape Breton Island. This title was hereditary within a clan and usually passed on to the Grand Chief’s eldest son.

The Grand Council met on an island on the Bras d’Or lake in Cape Breton called Mniku. Today the site is within the reserve called Chapel Island or Potlotek. To this day, the Grand Council still meets at Mniku to discuss current issues within the Mi’kmaq Nation. Taqamkuk was defined as part of Unama’kik historically and became a separate district at an unknown point in time.

The Mi’kmaq lived in structures called wigwams. They cut down saplings, which were usually spruce, and curved them over a circle drawn on the ground. These saplings were lashed together at the top, and then covered with birch bark. The Mi’kmaq had two different sizes of wigwams. The smaller size could hold 10-15 people and the larger size 15-20 people. Wigwams could be either conical or domed in shape.

Henri Membertou was born in 1507, died at the age of 104 on September 18, 1611. Before becoming grand chief, Membertou had been the District Chief of Kespukwitk, a part of the Mi’kmaq nation which included the area where the French colonists settled Port-Royal. In addition to being sakmow or political leader, Membertou had also been the head autmoin or spiritual leader of his tribe — who believed him to have powers of healing and prophecy.

Membertou was known to have acquired his own French shallop which he decorated with his own totems. He used this ship to trade with Europeans far out at sea, gaining first access to this important market and allowing him to sell goods at more worthwhile exchanges (“forestalling the market”).

Membertou became a good friend to the French. He first met the French when they arrived to build the Habitation at Port-Royal in 1605, at which time, according to the French lawyer and author Marc Lescarbot, he said he was over 100 and recalled meeting Jacques Cartier in 1534. His geniality and stature created a bond between the French and Mi’kmaq that helped to develop and prolong the historically important settlement in Port-Royal.

Both Lescarbot and explorer Samuel de Champlain wrote of having witnessed him conducting a funeral in 1606 for Panoniac, a fellow Mi’kmaw sakmow who had been killed by the Armouchiquois or Passamaquoddy tribe, of what is now Maine. Seeking revenge for this and similar acts of hostility, Membertou led 500 warriors in a raid on the Armouchiquois town, Chouacoet, present-day Saco, Maine, in July, 1607, killing 20 of their people, including two of their leaders, Onmechin and Marchin.

He is described by the Jesuit Pierre Biard as having maintained a beard, unlike other Mi’kmaq males who removed all facial hair. He was larger than the other males and despite his advanced age, had no grey or white hair. Also, unlike most sakmowk who were polygamous, Membertou had only one wife, who was baptized with the name of “Marie”. Lescarbot records that the eldest son of Chief Membertou had the name Membertouchis (Membertouji’j, baptized Louis Membertou after the then-King of France, Louis XIII), while his second and third sons were called Actaudin (absent at the time of the baptism) and Actaudinech (Actaudinji’j, baptized Paul Membertou). He also had a daughter, given the name Marguerite.

After building their fort, the French left in 1607, leaving only two of their party behind, during which time Membertou took good care of the fort and them, meeting them upon their return in 1610.

Three songs of Membertou survive in written form, and provide the first music transcriptions from the Americas. The melodies for the songs were transcribed in solfège notation by Marc Lescarbot. The time values of each note were recorded in an arrangement of Membertou’s songs in mensural notation by Gabriel Sagard-Théodat. The melodies use three notes of the solfege scale — originally transcribed as Re-Fa-Sol by Lescarbot, but more easily sung as La-Do-Re. Transcriptions of these songs are available for Native American flute.

On June 24, 1610, (Saint John the Baptist Day), Membertou became the first native leader to be baptized by the French, as a sign of alliance and good faith. The ceremony was carried out by priest Jessé Fléché, who went on to baptize all 21 members of Membertou’s immediate family. It was then that Membertou was given the baptismal name Henri, after the late king of France, Henry IV. Membertou’s Baptism was part of the entry by the Mi’kmaq into a relationship with the Catholic Church, known as the Mi’kmaw Concordat.

Membertou was very eager to become a proper Christian as soon as he was baptized. He wanted the missionaries to learn the Algonquian Mi’kmaq language so that he could be properly educated. Biard relates how, when Membertou’s son Actaudin became gravely ill, he was prepared to sacrifice two or three dogs to precede him as messengers into the spirit world, but when Biard told him this was wrong, he did not, and Actaudin then recovered. However, in 1611, he contracted dysentery, one of the many infectious diseases spread in the New World by Europeans. By September 1611, he was very ill. Membertou insisted on being buried with his ancestors, something that bothered the missionaries. However; Membertou soon changed his mind and requested to be buried among the French. He died on September 18, 1611. In his final words, he charged his children to remain devout Christians.

Aboriginal people have always played significant roles in Canada’s history. The spread of the fur trade, for example, and European exploration and settlement would not have been possible without the help of the First Peoples, who were relied upon for their knowledge and experience. Chief Membertou’s pivotal role in ensuring the survival of French settlement in eastern Canada made him a natural choice to be featured on the fourth stamp of Canada Post’s five-stamp French Settlement in North America series.

Scott #2226 was released on July 26, 2007. The 52-cent deep grey-blue, sepia, and bistre was printed by the Canadian Bank Note Company in sheets of 16, perforated 13.1 x 12.5. With no visuals of Membertou to work from, illustrator Suzanne Duranceau created his likeness based on written descriptions and documents. With the help of historian Francis Back, who conducted the historical research, Duranceau was able to create a portrait with a look and personality that reflected the many different written descriptions of Membertou that still exist today. The stamp’s background shows part of a typical Mi’kmaq canoe, and wigwams standing before the Port Royal settlement to show how Membertou and his tribe lived outside the walls of the settlement during the three years the Chief took care of the fort.

Designers Réjean Myette and Francois Martin went further with the design of this stamp than has been done with the other stamps in the series by printing the entire stamp only in engraving. Because of this, the designers had to choose colors that blended well together. Myette told Canada Post in an interview, “This decision pushed the printing method to its limits by printing all three colors at the same time on one engraved plate. This issue brings the engraving technique to a new level for stamps.”

Design, photography and photomontage were entrusted to the Montreal design firm of Fugazi, who also created previous stamps in the five-issue series. Suzanne Duranceau’s illustration was given to engraver Jorge Peral, a craftsman of international renown who is behind many of Canada Post’s detailed stamps. Four million of the commemorative domestic-rate stamps were printed on Tullis Russell paper, using offset lithography in 1 color plus 3 intaglios. General tagged on all four sides, the stamps are backed with P.V.A. type gum, each measuring 39.7 mm x 40 mm (vertical).

The official first day cover cancellation read St. Peter’s, Nova Scotia. The stamp issue is also unusual because the official first day cover contained text in English, French and Mi’kmaq. The text was written by Stephen J. Augustine, Hereditary Chief of the Mi’kmaq Grand Council and Curator of Ethnology for Eastern Maritimes in the Ethnology Services Division of the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Gatineau, Quebec. There were 31,400 first day covers prepared.

“The design and technical endeavors of this stamp were quite innovative, bringing the series dedicated to French settlement in North America to a new high,” said Alain Leduc, manager of Stamp Design and Production at Canada Post. “This is the first time that Canada Post has printed a three-color intaglio stamp using chablong technology. Design-wise, it was challenging to create a portrait of Membertou using only written references. We were fortunate to have been able to collaborate with people such as Stephen Augustine and Francis Back to ensure that the images and text we’ve used are historically accurate.”