The Liberation of Paris (Libération de Paris) was a military action that took place during World War II from August 19, 1944, until the German garrison surrendered the French capital on August 25, 1944. Paris had been ruled by Nazi Germany since the signing of the Second Compiègne Armistice on June 22, 1940, after which the Wehrmacht occupied northern and western France.

The liberation began when the French Forces of the Interior (Forces Françaises de l’Intérieur) — the military structure of the French Resistance — staged an uprising against the German garrison upon the approach of the United States Third Army, led by General George Patton. On the night of August 24, elements of General Philippe Leclerc’s 2nd French Armored Division made its way into Paris and arrived at the Hôtel de Ville shortly before midnight. The next morning, August 25, the bulk of the 2nd Armored Division and US 4th Infantry Division entered the city. Dietrich von Choltitz, commander of the German garrison and the military governor of Paris, surrendered to the French at the Hôtel Meurice, the newly established French headquarters, while General Charles de Gaulle arrived to assume control of the city as head of the Provisional Government of the French Republic.

Although the Allied strategy emphasized destroying German forces retreating towards the Rhine, the French Forces of the Interior (the armed force of the French Resistance), led by Henri Rol-Tanguy, staged an uprising in Paris.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, did not consider the liberation of Paris to be a primary objective. The goal of the U.S. and British Army was to destroy the German forces, and therefore end World War II in Europe, which would allow the Allies to concentrate all their efforts on the Pacific front.

Eisenhower stated that it was too early for an assault on Paris. He was aware that Adolf Hitler had ordered the German military to completely destroy the city in the event of an Allied attack; Paris was considered to have too great a value, culturally and historically, to risk its destruction. Eisenhower was keen to avoid a drawn-out battle of attrition, such as the Battle of Stalingrad or the Siege of Leningrad. It was also estimated that, in the event of a siege, 4,000 short tons (3,600 t) of food per day, as well as significant amounts of building materials, manpower, and engineering skill, would be required to feed the population after the liberation of Paris. Basic utilities would have to be restored, and transportation systems rebuilt. All these supplies were needed in other areas of the war effort.

However, General Charles de Gaulle of the French Army, upon seeing the French Resistance had risen up against the German occupiers, and unwilling to allow his countrymen to be slaughtered as had happened to the Polish Resistance in the Warsaw Uprising, petitioned for an immediate frontal assault, threatening to detach the French 2nd Armored Division (2e DB) and order them to single-handedly attack Paris, bypassing from the SHAEF chain of command, if Eisenhower delayed approval unduly.

On August 15, in the northeastern suburb of Pantin, 1,654 men (among them 168 captured Allied airmen), and 546 women, all political prisoners, were sent to the concentration camps of Buchenwald (men) and Ravensbrück (women), on what was to be the last convoy to Germany. Pantin had been the area of Paris from which the Germans had entered the capital in June 1940.

That same day, employees of the Paris Métro, the Gendarmerie, and police went on strike; postal workers followed the next day. They were soon joined by workers across the city, causing a general strike to break out on August 18.

On August 16, 35 young FFI members were betrayed by an agent of the Gestapo. They had gone to a secret meeting near the grande cascade in the Bois de Boulogne and were gunned down there.

On August 17, concerned that the Germans were placing explosives at strategic points around the city, Pierre Taittinger, the chairman of the municipal council, met Dietrich von Choltitz, the military governor of Paris. When Choltitz told them that he intended to slow the Allied advance as much as possible, Taittinger and Swedish consul Raoul Nordling attempted to persuade Choltitz not to destroy Paris.

All over France, from the BBC and the Radiodiffusion nationale (the Free French broadcaster) the population knew of the Allies’ advance toward Paris after the end of the battle of Normandy. RN had been in the hands of the Vichy propaganda minister, Philippe Henriot, since November 1942 until de Gaulle took it over in the Ordonnance (he signed in Algiers on April 4, 1944),

On August 19, continuing their retreat eastwards, columns of German vehicles moved down the Champs Élysées. Posters calling citizens to arm had previously been pasted on walls by FFI members. These posters called for a general mobilization of the Parisians, arguing that “the war continues”; they called on the Parisian police, the Republican Guard, the Gendarmerie, the Garde Mobile, the Groupe mobile de réserve (the police units replacing the army), and patriotic Frenchmen (“all men from 18 to 50 able to carry a weapon”) to join “the struggle against the invader”. Other posters assured that “victory is near” and promised “chastisement for the traitors”, i.e. Vichy loyalists, and collaborators. The posters were signed by the “Parisian Committee of the Liberation”, in agreement with the Provisional Government of the French Republic, and under the orders of “Regional Chief Colonel Rol” (Henri Rol-Tanguy), the commander of the French Forces of the Interior in the Île de France region. Then, the first skirmishes between the French and the German occupiers began. During the fighting, small mobile units of the Red Cross moved into the city to assist the French and Germans who were wounded. That same day in Pantin, a barge filled with mines exploded and destroyed the Great Windmills.

On August 20, as barricades began to appear, Resistance fighters organized themselves to sustain a siege. Trucks were positioned, trees cut down, and trenches were dug in the pavement to free paving stones for consolidating the barricades. These materials were transported by men, women, and children using wooden carts. Fuel trucks were attacked and captured. Civilian vehicles were commandeered, painted with camouflage, and marked with the FFI emblem. The Resistance used them to transport ammunition and orders from one barricade to another.

Skirmishes reached their peak on August 22, when some German units tried to leave their fortifications. At 09:00 on August 23, under Choltitz’ orders, the Germans opened fire on the Grand Palais, an FFI stronghold, and German tanks fired at the barricades in the streets. Adolf Hitler gave the order to inflict maximum damage on the city.

It is estimated that between 800 and 1,000 Resistance fighters were killed during the Battle for Paris, and another 1,500 were wounded.

On August 24, delayed by combat and poor roads, Free French General Leclerc, commander of the 2nd French Armored Division, disobeyed his direct superior, American corps commander Major General Leonard T. Gerow, and sent a vanguard (the colonne Dronne) to Paris, with the message that the entire division would be there the following day. The 9th Armored Company (“La Nueve“), composed of Spanish soldiers, veterans of the Spanish Civil War, were equipped with American M4 Sherman tanks, halftracks and trucks. They were commanded by French Captain Raymond Dronne, who became the first uniformed Allied officer to enter Paris.

At 9:22 p.m. on the night of August 24, 1944, the 9th Company broke into the center of Paris by the Porte d’Italie. Upon entering the town hall square, the half-track “Ebro” fired the first rounds at a large group of German fusiliers and machine guns. Civilians went out to the street and sang “La Marseillaise”. The leader of the 9th Company, Raymond Dronne, went to the command of the German general Dietrich von Choltitz to request the surrender.

While awaiting the final capitulation, the 9th Company assaulted the Chamber of Deputies, the Hôtel Majestic and the Place de la Concorde. At 3:30 p.m. on August 25, the German garrison of Paris surrendered and the Allies received Von Choltilz as a prisoner, while other French units also entered the capital.

Near the end of the battle, Resistance groups brought Allied airmen and other troops hidden in suburban towns, such as Montlhéry, into central Paris. Here, they witnessed the ragged end of the capital’s occupation, de Gaulle’s triumphal arrival, and the claim of “One France” liberated by the Free French and the Resistance.

The 2nd Armored Division suffered 71 killed and 225 wounded. Material losses included 35 tanks, six self-propelled guns, and 111 vehicles, “a rather high ratio of losses for an armored division”, according to historian Jacques Mordal.

Despite repeated orders from Adolf Hitler that the French capital “must not fall into the enemy’s hand except lying in complete debris”, which was to be accomplished by bombing it and blowing up its bridges, Choltitz, as commander of the German garrison and military governor of Paris, surrendered on August 25 at the Hôtel Meurice, the newly established headquarters of General Leclerc. Choltitz was kept prisoner until April 1947. In his memoir Brennt Paris? (Is Paris Burning?), first published in 1950, Choltitz describes himself as the savior of Paris.

In a 1964 interview, Choltitz claimed that he had refused to obey Hitler’s orders: “If for the first time I had disobeyed, it was because I knew that Hitler was insane”. According to a 2004 interview, which his son Timo gave to the French public channel France 2, Choltitz disobeyed Hitler and personally allowed the Allies to take the city safely and rapidly, preventing the French Resistance from engaging in urban warfare that would have destroyed parts of the city.

However, this version is seen as a “falsification of history” by communist and Resistance fighter Maurice Kriegel-Valrimont. In a 2004 interview, he described Choltitz as a man who “for as long as he could, killed French people and, when he ceased to kill them, it was because he was not able to do so any longer”. Kriegel-Valrimont argues “not only do we owe him nothing, but this a shameless falsification of History, to award him any merit.” The transcripts of telephone conversations between Choltitz and his superiors, which were found in the Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv in Freiburg im Breisgau (Baden-Württemberg), and analyzed by German historians, support Kriegel-Valrimont’s theory. Also, Pierre Taittinger and Raoul Nordling claim it was they who convinced Choltitz not to destroy Paris as Hitler had ordered. In 1958, Taittinger published …et Paris ne fut pas détruit (… and Paris Was Not Destroyed) describing the event, and was awarded the prix Broquette-Gonin from the Académie Française.

On August 25, the same day that the Germans surrendered, Charles de Gaulle, President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic, moved back into the War Ministry on the Rue Saint-Dominique. He made a rousing speech to the crowd from the Hôtel de Ville:

Why do you wish us to hide the emotion which seizes us all, men and women, who are here, at home, in Paris that stood up to liberate itself and that succeeded in doing this with its own hands?

No! We will not hide this deep and sacred emotion. These are minutes which go beyond each of our poor lives. Paris! Paris outraged! Paris broken! Paris martyred! But Paris liberated! Liberated by itself, liberated by its people with the help of the French armies, with the support and the help of all France, of the France that fights, of the only France, of the real France, of the eternal France!

Since the enemy which held Paris has capitulated into our hands, France returns to Paris, to her home. She returns bloody, but quite resolute. She returns there enlightened by the immense lesson, but more certain than ever of her duties and of her rights.

I speak of her duties first, and I will sum them all up by saying that for now, it is a matter of the duties of war. The enemy is staggering, but he is not beaten yet. He remains on our soil.

It will not even be enough that we have, with the help of our dear and admirable Allies, chased him from our home for us to consider ourselves satisfied after what has happened. We want to enter his territory as is fitting, as victors.

This is why the French vanguard has entered Paris with guns blazing. This is why the great French army from Italy has landed in the south and is advancing rapidly up the Rhône valley. This is why our brave and dear Forces of the interior will arm themselves with modern weapons. It is for this revenge, this vengeance and justice, that we will keep fighting until the final day, until the day of total and complete victory.

This duty of war, all the men who are here and all those who hear us in France know that it demands national unity. We, who have lived the greatest hours of our History, we have nothing else to wish than to show ourselves, up to the end, worthy of France. Long live France!

The day after de Gaulle’s speech, Leclerc’s French 2nd Armored Division paraded down the Champs-Élysées. A few German snipers were still active, and ones from rooftops in the Hôtel de Crillon area shot at the crowd while de Gaulle marched down the Champs Élysées and entered the Place de la Concorde.

On August 29, the U.S. Army’s 28th Infantry Division, which had assembled in the Bois de Boulogne the previous night, paraded 24-abreast up the Avenue Hoche to the Arc de Triomphe, then down the Champs Élysées. Joyous crowds greeted the Americans as the entire division, men and vehicles, marched through Paris “on its way to assigned attack positions northeast of the French capital.”

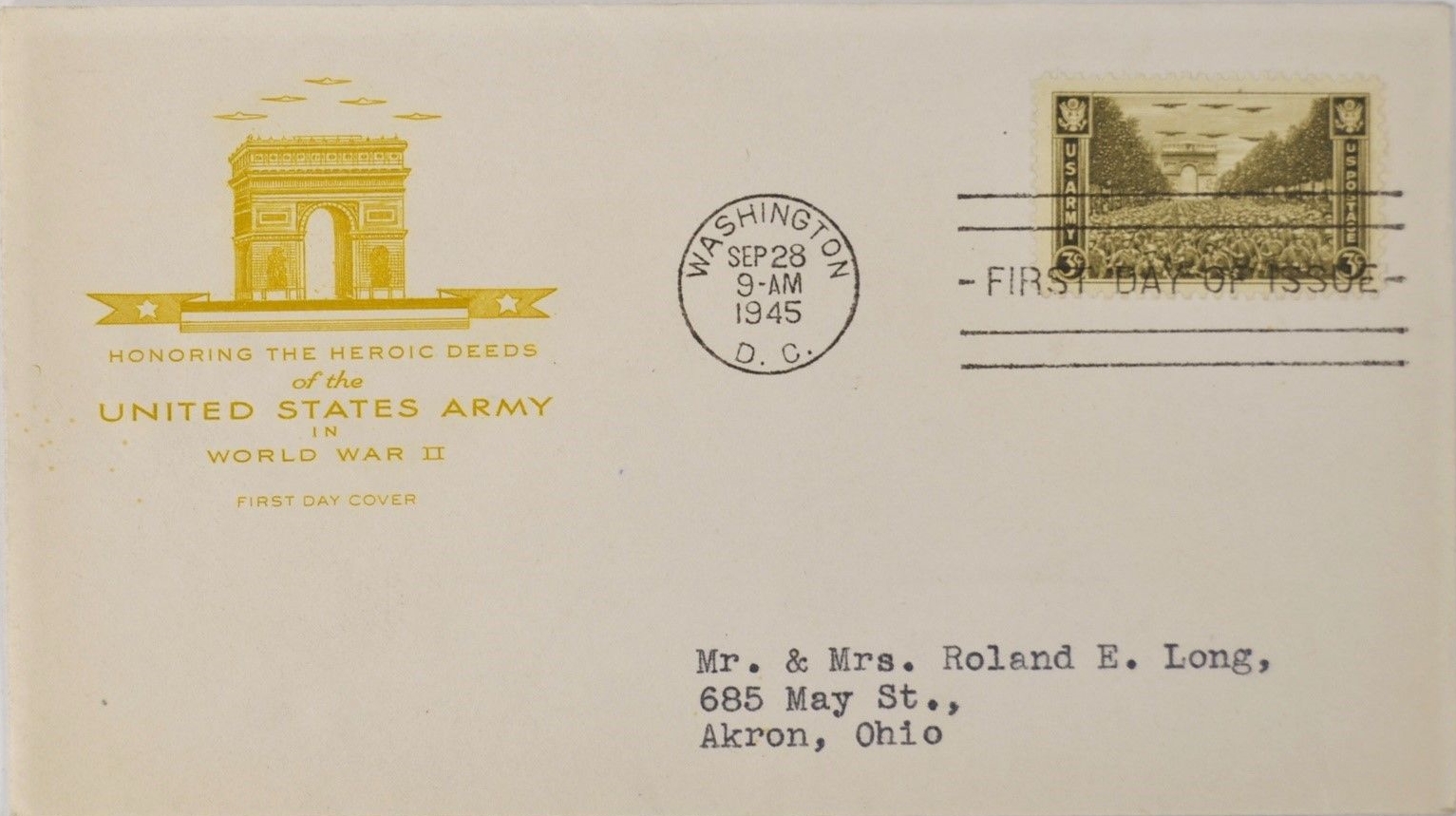

On July 14, 1945, U.S. Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson submitted Associated Press photographer Peter J. Carroll’s photograph of the August 29 parade to Postmaster General Hannegan to be used as the basic design for a stamp issue which was planned to honor the U.S. Army’s achievements during World War II. By July 31, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing had already submitted two models of the proposed stamp (in vertical and horizontal formats) to the third postmaster general. By August 2, the horizontal design had received initial approval in the Pentagon and was sent on to Stimson for his sign-off before being returned to the postmaster general.

As the stamp was on the fast track to completion, Washington Sunday Star’s philatelic editor, J. W. Fawcett, responded with a published complaint that a photograph of the Remagen Bridge had not been used as the source for the design, as he had announced earlier. He also challenged the authenticity of war planes appearing in the Paris sky, to which the third assistant postmaster general responded:

“Possibly the introduction of planes in this design by the War Department was for the purpose of paying incidental tribute to the Air Force. . . . The mere fact that the subject matter for the Army stamp was submitted from an outside Agency . . . does not relieve the Post Office Department from seeing that the material approved is completely appropriate and conforms with recognized standards. The design . . . does not portray in recognizable manner the features of any living individual . . . is not intended as a faithful reproduction of any well-known photograph . . . and in my opinion is completely satisfactory as well as effective in honoring the victorious Army of this country.“

On September 28, 1945, the United States Post Office Department issued the three-cent khaki stamp commemorating the liberation of Paris from the Germans (Scott #934). The official press release announced, “The central design of the Army stamp is a reproduction of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, through which hundreds of United States soldiers are marching.” Over a year later the wording in the press release would be contested by 1st Lt. George R. Becker. War Department investigations, official photographs, and first-hand testimony confirmed that troops had been routed around the monument, which stands over the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier of France. The identity of the troops in the picture had not been made public but consisted largely of the “1st Battalion, 112th Infantry Regiment of the famous 28th Infantry Division, while the extreme right portion of the stamp illustrates the 1st Battalion, 110th Infantry Regiment of the same division.”

There were 128,357,750 copies of the stamp printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing on the rotary press, perforated 11 x 10½.

One thought on “The Liberation of Paris”